⚠️🚨RED ALERT: This episode pulls together everything we talked about over the first four episodes. It will make very little sense to you (and feel wildly overclaimed) unless you’ve read/listened to episodes 1:1, 1:2, the first part of 1:3 (up through the introduction of the lovers possibility), and the first half of 1:4 (up to the “a priori” reasoning relative to the lovers possibility). You’ll also have a richer experience of this episode if you’ve read/listened to the Beatlemania Rabbit Hole (which is really the back half of episode 1:3), but that’s optional.

Also apologies for the audio glitch in this morning’s original post. It was bound to happen soon or later and today was the day. It’s been fixed

All the episodes of Beautiful Possibility in sequence are here.

In the woods on the outskirts of Liverpool, down the path from the newly constructed council estate of Allerton, a small boy with dark hair and large, soulful eyes holds a squirming frog in his hands. The little boy loves animals. And he also loves art and literature and music.

But he also knows that in just a few years — like every boy in England — he’ll have to spend two years in the army. His stomach twists at the thought of it. But he knows it’s what all boys have to do, before they can become men. And he knows from his time in the Boy Scouts that the most important thing for boys to learn — if they want to become men — is to learn to be a soldier.

The little boy has an especially vivid imagination. So he tries to imagine himself fighting in an actual war, sticking a bayonet into a living being. He wonders if he can. Wonders what will happen to him if he can’t. Probably he’ll have to go to prison, he thinks. That’s what they do with men who won’t go to war. He tries to imagine himself in prison. Tries to imagine what he’ll be called when he gets out. Traitor. Weakling. Coward. Soft.

The little boy looks down at the frog squirming in his hand. Then he looks up at the barbed wire fence, and then down at the frog again, and the frog looks back at him.

In the years to come, the little boy will teach himself to play guitar and to sing and to write songs that will tip the world on its axis. And on that afternoon, in the woods outside of Liverpool and because the culture told him he had to, to win its approval, Paul McCartney — the little boy with the dark, soulful eyes who loves animals and art and literature and music — will teach himself to kill.

“All my mates killed frogs anyway,” Paul would remember years later. “I used to stick "em on the barbs of the wire. I had quite a little gallery... I remember taking my brother down there once. He was completely horrified.”1

A little over ten years later, in the lobby of Abbey Road Studios, an auburn-haired man wearing rounded National Health glasses stares down at the wilted rose in his hand and wonders what the girl — one of the usual knot of fans at the front steps — meant by giving it to him when he’d arrived moments ago. A wilted rose could mean so many things on that warm spring day, when everything around him seemed to be wilting. The Beatles, the Sixties, his creative inspiration, his public image. Paul.

He hadn't wanted anything to do with the fucking rose, had refused it, initially. But the little twit who held it out to him had burst into tears right there in front of everyone, and what the fuck was he supposed to do, except take the sorry-looking thing and get inside as quick as he could, before the whole thing turned into some kind of a scene.

I don't think it was symbolic of anything, George tells him, once there's a door and Big Mal between him and the weeping girl. It was probably fresh this morning when she got here.

Well, fucking hell.

He looks down at the rose again, the latest in a long line of scenes he’d rather forget, marching like jack-booted soldiers through his memory, filed under ‘hard walls built between him and his pain’ — broken bottles and bloody noses, black leather and bluster, slags and taunts and a trail of hurt feelings, a weeping girl and a wilted rose.

All you need is love, right? he hears George say quietly behind him.

They talk about love a lot these days, and how it’s the only answer. But somewhere along the way — it’s all something of a haze, but maybe around the time he’d decided only to sing words he actually meant — he’d stopped singing about love as anything other than pain.

Fucking hell.

Directing one of the courtiers to ask the girl inside, he carries the rose to the wash basin, holds it carefully beneath the water in a fruitless but all at once urgent need to revive it. And in doing so, on that spring day in 1969 — if only for a moment — John Lennon lets his walls down and softens back into himself.2

Having taken the last few episodes to begin to establish the credibility of the possibility that Paul and John were a romantic as well as a creative couple — again, not the certainty but the possibility — we’re now ready to return to our story about the story of The Beatles.

Before we get started, if you connected with Beautiful Possibility partway through — as I know most of you did — and if you haven’t yet gone back and listened to the first few episodes, we’ve arrived at the point where it really matters that you’re caught up with those earliest episodes — because this is where we take everything that we’ve talked about up to this point and put it all together. And if you haven’t yet read or listened to those first couple of episodes, before the lovers possibility was introduced, this episode is unlikely to make much sense to you.

In addition, without an understanding of how mythological stories interact with culture, and how the story of The Beatles has shaped the mythological riverbed of our modern world — all of which is covered in those first few episodes — the conclusions at the end of this episode will almost certainly feel improbable and wildly overclaimed.

And more than that, without the context of those first few episodes, you’ll be missing the more profound — and more beautiful — reason why restoring the possibility that John and Paul were lovers matters so much to the story and to our world — which is more or less the whole point of Beautiful Possibility. Because restoring the lovers possibility to the story requires not just that it be credible and ethical, but also that it matters that we do.

So with that said then, as we continue for the final three episodes of Part 1, I’m going to assume that you’re all caught up on our mythological story of the story of The Beatles, and we’ll pick up where we left off in that story.

As we’ve covered at length in prior episodes, during and after the breakup, John was the only one talking to the press in any detail about what had happened. And because John was the only one talking to the press, he was the one who framed the story of both the breakup and of the band. And his version of the story was subsequently canonised in all those articles and books. Remember Jann Wenner’s claim in the foreword to Lennon Remembers — where he ignores John’s retractions and contradictions and asserts that John’s interview stands as the definitive word on the breakup and the band, “because John was the leader of the group.”

I want to pause here for a moment, before we get too far into all of this, and clarify something that I’m not sure I made clear enough in prior episodes. By focusing on John’s breakup narrative and the damage that resulted from it, I don’t mean to imply that John is solely at fault for either the events of the breakup or for what followed. He was the one framing the narrative, but as I’ve emphasized, he was doing so while struggling with what seems to have been a psychic breakdown of extreme proportions, perhaps beginning with their trip to India, and intensified by his drug use, his fear of abandonment resulting from his difficult childhood, his aborted primal scream therapy, his creative insecurity and life-long low self-esteem, and his broken heart at his estrangement with Paul.

Breakups are complicated, and they’re rarely the result of one person’s actions. And this breakup is especially complicated. Lots of people contributed to what happened, including Paul, George, Yoko, Brian’s death, and a few bit players and several additional elements that we haven’t yet talked about — and we’ll get to all of that when we get there in the re-telling of the story in the next part of Beautiful Possibility.

We’re focusing for now on John’s breakup narrative because we have to start the chain of cause and effect somewhere, and because in this first part of the series, we’re telling the story of the story of The Beatles. And since John was the one who framed that story as it’s been handed down to us, that’s a reasonable place to pick up the thread.

So again, I’m not at all intending to lay the blame for the breakup or its aftermath on John. But it’s also without question true that — as we’ve already seen in some detail — John’s Breakup Tour did considerable damage. And as I suggested in an earlier episode, of all the damage John did on his Breakup Tour, by far the most damaging of all was what he said about his partnership with Paul. And more specifically, his self-acknowledged lie — John’s word, not mine — that he and Paul never actually wrote together.3

When John claimed that Lennon/McCartney was a fiction, he effectively — and almost certainly unintentionally — set into motion a chain of events that rewrote the story of The Beatles and our collective experience of both that story and the music. And because that story is the foundational myth of our modern world, the consequences of that chain of events to the lives we’re all living today are... well, let’s just follow the trail and see where we end up.

Throughout the Sixties, the world had experienced Lennon/McCartney as an impenetrable and indivisible partnership — a closed circle of two enfolded in a closed circle of four. And the main reason for this is that John and Paul had stayed true to their covenant that all of their songs belong to both of them equally — which as we talked about in a prior Rabbit Hole, is true even for the handful of songs that were technically written solely by one or the other. “Yesterday” was as much John’s as it was Paul’s, when it came to our experience of their partnership.

But when John claimed that he and Paul never wrote together at all, he broke that covenant. And in doing so, he shattered the formerly indivisible unity of the Lennon/McCartney partnership, and split the story — and the music — of The Beatles from a single greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts whole into two separate halves — songs that John wrote and songs that Paul wrote. And that — plus John’s anger and heartbreak as he did it — split Lennon/McCartney into Lennon vs. McCartney. JohnandPaul into John vs. Paul.

We talked in a prior episode about how Paul and Brian seem to have been the only two people who could stabilize John’s emotional volatility enough to allow him to function in the band and in the world in general.4 But now Brian was dead and John was estranged from Paul, and there was no one with the emotional sensitivity to save John from his destructive impulses, and plenty of people eager to encourage them. And of course the journalists who interviewed John had no interest at all in protecting John from those destructive impulses— they were too busy indulging their own. (And we’ll get back to the destructive impulses of the press later in the episode.)

For the first time since 1957, John had no one to stabilize him, and so he did what most people in emotional crisis do if they don’t have anyone capable of helping them through it — he reverted to his old coping mechanisms. And those coping mechanisms mostly involved burying his own pain in anger by striking out at those he felt had hurt him — and, of course, mostly Paul.

If you have even a conversational grasp of the language of the Grail, it’s not at all difficult to see John’s distorted “we never even wrote together” narrative as the product of a broken heart. It’s exactly the sort of thing someone who is deeply in love might say when they’re heartbroken and unable to communicate that love — I never loved you and you never loved me, we weren’t even all that close, really, so there’s nothing to be heartbroken about, and also to make my own pain easier to bear, I’m going to hurt you the way you hurt me.

But even beyond his broken heart, it’s easy to see that John had another motivation for striking out at Paul during the breakup — and that’s, of course, John’s creative insecurity, especially relative to Paul — the very same insecurity that we talked about in some detail in our “day trip to “Unscrambling Yesterday” a couple of weeks ago.

But we don’t have to look too much further to find evidence of it than John’s admission that “How Do You Sleep?” was written not about Paul, but about John himself. That it was a confessional song that reflected John’s own post-breakup fears about having to compete, rather than collaborate, with Paul McCartney — a daunting prospect for anyone, even and perhaps especially John Lennon, who knew better than anyone else the depth of Paul’s genius, but seems to have had only occasional awareness of the depth of his own.5

Beatles press officer Tony Barrow described John’s insecurities in his 2005 memoir—

“Beneath the bullet-proof exterior I had found a pitifully insecure man who doubted his own abilities and couldn't concentrate long enough on his songwriting to complete more than a fraction of his best work. He had heaps of unfinished songs surrounding him throughout the time I knew him best in the Sixties.”6

John’s insecurity was never far from the surface at any time ever, and he was almost certainly feeling more insecure during the breakup than at any other time in his adult life, as he faced a solo career outside of the protective creative bubble of The Beatles that he’d been sheltered in since 1957.

As we’ve talked about in prior episodes, his partnership with Paul — and The Beatles as a whole — seem to have been a safe space for John. In addition to Paul and Brian’s stabilizing influence, the collaborative structure of the band and the joint Lennon/McCartney credit meant that it was virtually impossible to separate out one member’s contribution from the rest (despite the post-breakup journalistic obsession with doing just that). The collaborative nature of the group and of Lennon/McCartney was, of course, one of the keys to their magick. And it had the added benefit of protecting John from his insecurity by not revealing the exact contours of his individual talent — which might be part of the reason it was set up that way in the first place.

Now you and I and more or less the whole world knows John Lennon had absolutely nothing to worry about when it came to the magnitude of his genius — but it’s also abundantly clear that John didn’t know that. And after the breakup, there was no one and nothing to shield him from having to stand on his own, creatively, and thus revealing his most shameful secret to the world — that — in John's mind — he was a fraud and that Lennon/McCartney was actually mostly McCartney.

More specifically, it’s likely that John knew full well that it was Paul — and only Paul — who knew not only how to stabilize John emotionally, but also to translate John’s creative ideas into their fullest expression, the only person who understood what John meant when he said things like, “I want it to sound orange.”7 Without Paul to interpret John’s iconoclastic creative ideas, for the first time ever, John was left on his own to figure out how to realise the sounds he heard in his head. And John had never before had to do that, not even one single time.

For all of John’s bluster and bravado about how great it was to work on his own, there’s no scenario in which this wasn’t a disorienting, terrifying experience for him. It’s the kind of experience that would be virtually certain to spin an insecure, volatile genius afraid of creating on his own — without a close (and equal) collaborator — into a full-scale panic.8

John tried, of course, to duplicate what he’d had with Paul and to once again disguise the specific contours of his own talent by melding his solo work tightly to Yoko’s influence and declaring her to be a musical genius on par with — and even exceeding — Paul. But whatever Yoko’s talents as a visual artist, we all know — as did virtually everyone at the time, and probably even John and maybe even Yoko — that Yoko was fundamentally incapable of stepping in for Paul McCartney as a songwriting partner, duet partner, musician, or arranger.9 And John’s breakup behaviour also makes it pretty clear that Yoko did not have the ability that Paul and Brian had to stabilize John emotionally — he was perhaps more volatile and angry during those breakup years than he’d been at any other time in his life.

It seems pretty clear that John didn’t fully think this part of things through, when he burned it all down.10

To make things worse still, John’s insecurity was almost certainly sent into extreme overdrive by the external pressures after the breakup. As each Fab launched a solo career, the expectations — especially for Solo John and Solo Paul — were, of course, stratospherically — and unreasonably — high. And those unreasonably high expectations persist right up to this very day.

Before we go further, let’s do a mini Rabbit Hole, and take a few minutes to talk about those unrealistic expectations — because those expectations did and continue to do harm, not just to The Beatles, but to any artist whose work we admire.

Our expectations of both John and Paul — together and as solo artists — have always been unreasonable because our expectations of artists are always unreasonable, even — and maybe especially — if the artists in question are world-changing creative geniuses.

Our collective tendency to think of art as a consumer product leads us to demand that the artist produce a constant, unbroken upwards trajectory of work. We demand that each new creation be better than the last one, an endless assembly line of ever-more transcendent masterpieces — and in doing so, we’re utterly oblivious to the reality that art just doesn’t work that way.

Art isn’t like the latest iPhone. It’s not the nature of art to evolve in an endless iteration of upgrades. Art — even by creative geniuses — is far more ephemeral, unpredictable, and fragile than that.

An artist — and especially a great artist — inevitably goes through creative cycles, as they experiment with different styles and approaches, synthesizing new influences, trying new ideas. Sometimes that experimenting leads to artistic leaps forward and sometimes it doesn’t. But rarely does it happen in a constant, unbroken upward trajectory.

And then there’s the expectation that artists will be capable of creating new work at even their previous levels of quality when they’re in the midst of a personal crisis, regardless of how distracted or heartbroken or in psychic distress they might be.

We don’t consider any of that, when we make our demands and register our disappointments that art fails to live up to our unreasonable expectations. Nor do we consider that those ever-escalating expectations risk destroying the very artists we claim to love, when they fail to deliver on our unreasonable expectations, and eventually burn themselves out trying to please us — as John burned himself out, and as Paul very nearly did.11

And yet, a constant — and dramatic — upward trajectory is in fact what The Beatles delivered throughout most of their creative life together. That’s one of the things that makes what they accomplished so astounding. But that constant upward trajectory also created the wildly unrealistic expectations that we had — and continue to have — for them as solo artists. And it’s also probably why we expected that — somehow — that constant upward trajectory would continue into their solo work.

Even as we all agree that they were exponentially more together than they were separately, we also demand that John and Paul separately somehow manage to create Beatles-level music on their own — which of course makes no sense at all, even just mathematically.

If we know two people together are more than the sum of their parts, then it’s irrational and wildly unfair to simultaneously expect each of the partners individually to add up to what they are together — and even more unfair to criticize them when they fail to live up to our irrational expectations.

But this is exactly what we expected — and continue to expect — of both John and Paul as solo artists. And even more selfishly, we also expected both of them to deliver Beatles-level music during and after the breakup, when they were both struggling with distraction, exhaustion, crippling emotional trauma, substance abuse, and heartbreak.

We gave — and still give — John and Paul no leeway, no breathing room, no opportunity to be “less” than what they’d been during the Beatles years. No opportunity to be human and fallible. Even still today, we judge the quality of their solo work by how close it gets to what they did together during the Fab years — and when I say “we,” I’m including myself, even though I try very hard not to.

But of course, that’s a standard that by definition sets both of them up to fail, given we also collectively acknowledge that the two of them separately can never be what they were together. What they were together is a big part of what we lost in the breakup — and what we mourn for, especially knowing it was lost forever the day John was murdered.12

Neither Paul nor John helped matters, of course, when they indulged their admittedly unhelpful tendency to release into the wild what seemed like every half-baked song idea they’d ever had. And of course, we criticized them for that, too, forgetting that creating art, for an artist, isn’t just about pleasing us.

Creating and sharing art is how an artist heals their pain — and especially when both Paul and John have told us that they, like many artists, use their art as therapy. We know John used his early solo work as a way to work through his pain, but we don’t often recognise that Paul, especially given his difficulty in sharing his innermost feelings, did the same. “McCartney,” Paul acknowledged in 2007, “was a kind of therapy through hell.”13

Here’s Paul again in 1984 talking about those early solo days—

"Those are the songs that some people thought were not as good as my earlier stuff, or too commercial. I know people from time to time used to say that, but my attitude was, 'Sorry, folks, it's about the best I can do right now. Sorry! You know, this is me trying to do it. I'm trying to do it honestly and genuinely; if some of it's not working to your taste, what can I say?' But it helped us claw our way back."14

We expected — and still expect — John and Paul to deliver on their own the same level of artistry as they had together, even while we continually — and often brutally — remind them that they needed each other to rise to Beatles level. We expected — and still expect — them to work at ever-escalating levels of artistic mastery, despite whatever personal pain they may be going through at the time.

And yet despite those wildly unrealistic and unfair expectations, incredibly, both John and Paul did deliver — with solo albums we recognise in retrospect (though many didn’t recognise at the time ) as genre-inventing masterpieces. Paul’s first solo album, McCartney, is now recognised as the first “make music in your bedroom” album, and his second solo album, Ram, is recognised by most people qualified to have an opinion as having invented the indie rock approach to music-making that would later develop into bands like the Replacements and REM. And John’s Plastic Ono Band is probably music’s first — and still rawest and most iconic — singer/songwriter confessional album.

All of that is the wisdom of hindsight, of course. And those unrealistic expectations — combined with John’s creative insecurity — would almost certainly have made it hard for Breakup John to resist pushing Paul down so as to lift himself up. Again, this isn’t surprising. It’s what insecure people do when they don’t know a healthier way to deal with their insecurity, and in the face of overwhelming creative pressure.

When I first started researching this part of the story, one question I kept coming back to was, why were journalists so willing — and even eager — to ignore John’s retractions and contradictions, and to believe John when he said that he and Paul never wrote together? Why did they so willingly throw away the world-changing magick of The Beatles, of Lennon/McCartney, and shift their loyalty to ‘John vs. Paul’ — when that version of events is such a bleak story compared to the truer one? And why do so many people — and especially men — still cling to that toxic, distorted story of ‘John vs Paul’ even today, when the truer story is so much more beautiful and life-affirming?

Before we answer those questions, it’s important to acknowledge that ‘John vs. Paul’ isn’t entirely inaccurate. Even beyond John’s breakup interviews, the lawsuits, diss songs and public catfights gave the press plenty of raw material to work with to construct the ‘John vs. Paul’ narrative.

And outside of the breakup, this creative competition between John and Paul isn’t by definition a bad thing. Of course there was creative tension and passionate argument, each trying to outdo the other, as Paul sings in “Tug of War”— all of it amplified by John’s insecurity and depression and impatience, and Paul’s, shall we say, extreme attention to detail and indefatigable work ethic,15 and also a collection of other more complicated things that we’ll talk about when we get there in the story.

There seems little doubt that John and Paul’s mutual tug-of-war was an important part of their creative dynamic.16 17 Their creative competitiveness may also be partly responsible for the astounding speed with which The Beatles innovated — reinventing pop music with each new album, never repeating themselves, always reaching for the next incarnation of their artistic vision, as they pushed each other to greater and greater creative heights.

Here’s Paul talking about this in 2004—

“There was amazing competition between us and we both thrived on it. In terms of music, you cannot beat a bit of competition. Of course, there’s times when it hurts, and it’s inevitably going to reach a stage where it’s hard to live with. Sooner or later, it’s going to burn itself out. I think that’s what happened at the end of The Beatles. But, for those early years, the competition was great. It was a great way for us to keep each other on our toes. I’d write “Yesterday” and John would go away and write “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)”. I’d come up with “Paperback Writer” and John would come back with “I’m Only Sleeping”. If he wrote “Strawberry Fields”, it was like he’d upped the ante, so I had to come up with something as good as ‘Penny Lane’”1819

But even here, I wonder if it was actually competition in the way that word is usually meant. Because there’s writing to outdo one another, and then there’s what Paul seems to be talking about here — which is more about writing to impress, and even dazzle, one another, even more than to impress and dazzle the outside world. Those two things — wanting to best someone and wanting to impress and dazzle someone who’s at an equal level of talent — might look the same to the outside world, but they’re rooted in entirely different mindsets.

Competing with someone, even when it’s “healthy” competition, is really just another iteration of “might makes right” — dominating the other person using the strength of one’s talent. But writing to impress a creative partner — if that other person is a co-equal in terms of talent — is more about wanting to delight and dazzle them, in the same way that a lover might put on their best clothes for an evening out, to impress, and to please, their beloved.

And from that perspective, it’s also possible — and maybe even likely, based on things each of them has said — that there was an erotic charge to John and Paul’s creative tug-of-war.

I pointed out in a prior episode that Paul and John consistently use erotic metaphor to describe their creative process in a way they don’t use to describe their creative process with anyone else. Aside from the obvious possibility that they’re cloaking their literal romantic relationship in metaphor, in another sense, it might not be metaphor at all. Writing together may have quite literally turned them on in the erotic as well as the creative sense of the word — and part of the turn-on may have been the endorphin high of writing to impress and dazzle one another.20

I don’t think this is much of a reach. In my experience, the endorphin high of competition often feels similar to sexual arousal, even when you’re not in love with your rival. And it wouldn't be the first time two highly competitive people in a romantic relationship played out their desire in their creative lives — although it is the first time doing so was so powerful that it changed the underlying mythological riverbed of an entire civilization.

But all of that said, it is — like most things in this story — not an either/or, but a both/and.

Defining their relationship only as competitive without the collaboration misses the complexity and the paradox and arguably the deeper source of their power — two geniuses deeply in love, intensely attracted to one another and fiercely competitive all at the same time. When we strip any of those elements out — the love, the desire or the competition, we lose any chance we have of untangling the mysteries of Lennon/McCartney.

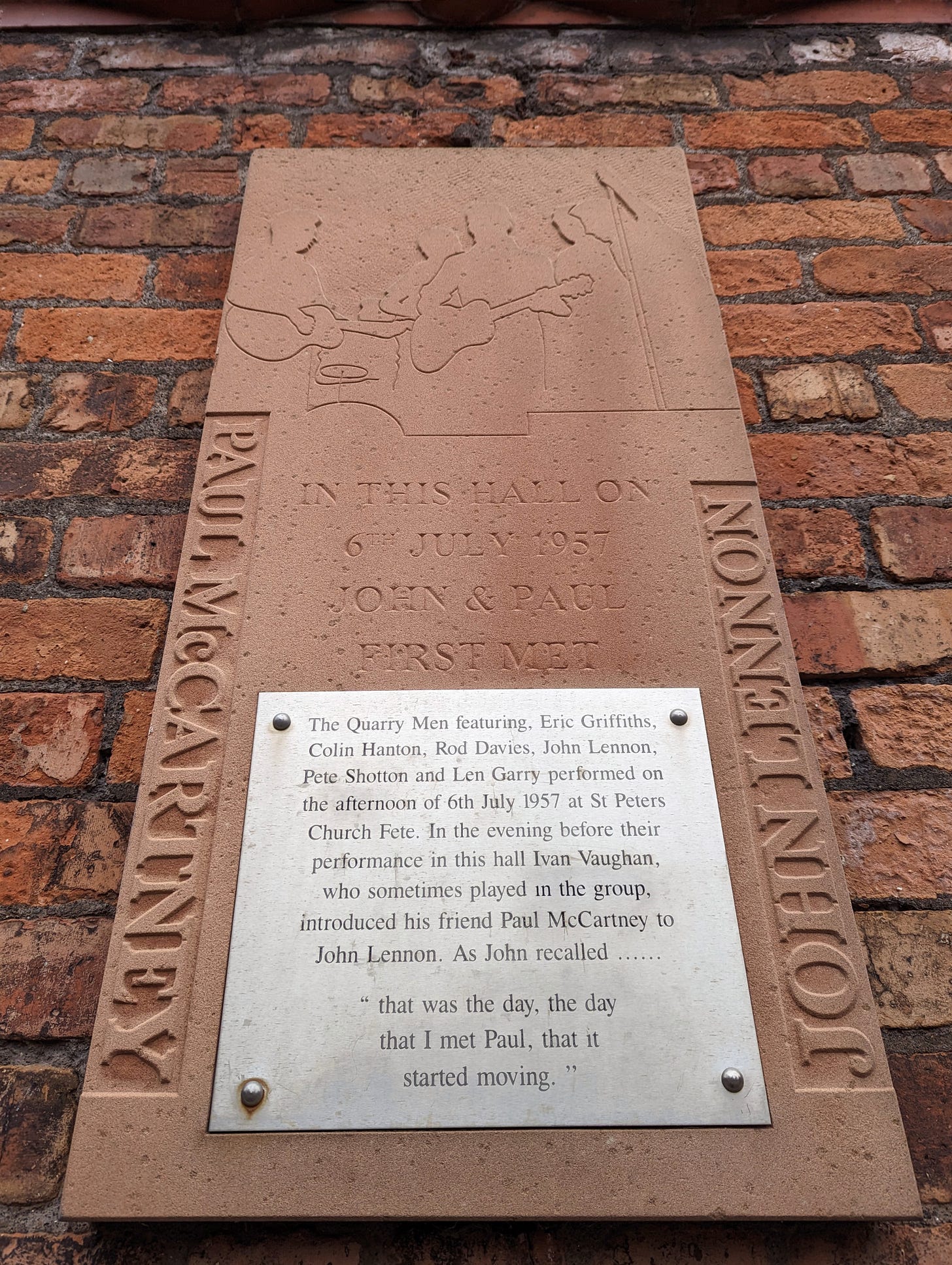

There’s a reason we mark the day John and Paul met as the day The Beatles began. There’s a reason that for the past fifty years, a steady stream of people of all ages and from all over the world have made the pilgrimage to St. Peter’s Church Hall, where a brass plaque commemorates the day and place that John and Paul met. And there’s a reason that plaque has John’s quote engraved on it — That was the day, the day I met Paul, that it started moving.21

We mark the day and place John and Paul met because we instinctively recognise their first meeting as The Beatles’ origin story, even if John hadn’t explicitly told us so. We don’t mark the day John founded the Quarry Men, or the day Paul bought his first guitar, important as those events are. We mark the day two boys who loved rock and roll and desperately wanted a life that was better than “suffer now, rewards later” found what they’d been searching for in one another, and became incalculably more together than their individual genius could have allowed them to become separately.

What’s iconic and transcendent and world-changing about Lennon/McCartney is, quite simply, that they were Lennon/McCartney, not Lennon vs McCartney. And not even Lennon & McCartney, with the ampersand and the space between them, as prior songwriting duos had styled themselves — but Lennon/McCartney, separated by only the thinnest of lines. The magick is in the joining of their two names, in the complex, passionate, fiercely exclusionary intimacy of their partnership.

That magick is made manifest in their accounts of the intensity of their connection when they wrote together, and in their insistence on keeping their writing sessions private — those two things probably being intimately related.22 And perhaps most of all, in their insistence from the very beginning — when Paul wrote “Another Lennon/McCartney Original” at the top of that first notebook — in their shared and exactly equal credit on every Lennon/McCartney song, regardless of the fussy details of who wrote what23 — which is why monkeying with the credit order even on “Yesterday” feels like a fundamental disruption of the magick of Lennon/McCartney, perhaps the modern world’s most powerful incantation of partnership and the alchemical sorcery of the whole being more than the sum of its parts.

And while this series focuses on John and Paul, the world-changing magick of The Beatles is also, of course, in the four of them together — John, Paul, George and Ringo — being so much more than the sum of their individual parts.

George Martin described this 1969, in his instructions to a new staffer on how to engineer a Beatles recording session—

“There will be one Beatle there, fine. Two Beatles, great. Three Beatles, fantastic. But the minute the four of them are there that is when the inexplicable charisma thing happens, the special magic no one has been able to explain. It will be very friendly between you and them but you'll be aware of this inexplicable presence. Sure enough, that’s exactly the way it happened. I’ve never felt it in any other circumstances, it was the special chemistry of the four of them which nobody since has ever had.”24

From the beginning, that collaboration was built into the structure of the band, starting with the deliberate lack of a clear frontman, which — odd as it might be to imagine now — was unprecedented at the time for a rock-and-roll band. It wasn’t ‘Paul McCartney & the Beatles’ or ‘John Lennon & the Beatles,’ and thankfully ’Johnny & the Moondogs’ lasted all of about five minutes. It was simply “The Beatles.”25

And then there was the standing rule that every decision required a unanimous vote, and that any member of the band could reject any song they didn’t think was good enough for a Beatles album. And the songs that did make the cut included no self-indulgent solos and no elevating of any one member’s contribution above the others in the arrangements — with the exception of “Yesterday,” which as we saw in our day trip, created no end of troubles between John and Paul for just that reason.26

But other than “Yesterday,” what we hear on Beatles records is simply, elegantly, The Beatles, the “four-headed Orpheus,” as ‘60s cultural writer George Melly once put it27 — which is why those very same journalists who helped split them apart by relentlessly stoking the rivalry between John and Paul simultaneously hounded them relentlessly to get back together.

The answer to why journalists so eagerly turned their backs on the more magickal — and truer — story of Lennon/McCartney in favour of ‘John vs. Paul’ might be found in looking more closely at exactly what it was John was saying — and not saying — about Paul in those interviews.

When I went looking for what John had actually said about Paul in interviews during and after the breakup, I was surprised at what I found — or rather, at what I didn’t find.

Because curiously, what John did say in his Breakup Tour isn’t the ‘John vs. Paul’ story that appears in all those books that have shaped the story that’s been handed down to us — the version of story that insists not only that John and Paul weren’t close and didn’t write together, but that John is the sole genius of The Beatles, or at least the only one who really counts, and that Paul is nothing more than the “cute” Beatle, lightweight and insubstantial compared to John’s towering brilliance.

What I did find in John’s breakup interviews is a lot of what one would expect to find in any bad breakup, from a wounded lover struggling with a broken heart — a jumbled collection of petty grievances and “it’s because you fucked up the tambourine that my life is a misery,” as John acknowledged in one of his retraction interviews.28 That’s all to be expected — it’s what we tend to do when we have a broken heart — focusing on every little complaint blown up into more than it was as a way of rationalising that we’re better off without our beloved.

Of course, most of us vent this sort of thing in private to trusted friends, rather than into the microphones and TV cameras of the world’s press. But despite all of John’s bitterness and rage — and contrary to popular belief — I’ve found only a single, sidways example in which John denigrates Paul’s genius, (which we’ll get to in the next episode), and I’ve found no instances at all of John suggesting Paul was anything other than a full and equal creative partner. And as we saw in a prior episode, John regularly makes clear that he loves Paul in spite of their current difficulties, and that he regards their estrangement as temporary and not a permanent rift.

John also makes it clear in multiple interviews — I’ve found at least four references so far — that he’s not okay with anyone else saying anything negative about Paul in any context. That, with trademark Lennon-esque logic, only he gets to say nasty things about Paul, no one else does. “I’m entitled to call Paul what I want to, and vice versa; it’s in our family,” John said in 1974, “but if somebody else calls him names, I won’t take it.”29

All of this would seem to make it abundantly clear that however wounded he was during the breakup, John wasn’t out to do any lasting harm to Paul in those interviews.

So where does the ‘John is the sole genius of The Beatles and Paul is the lightweight sidekick’ version of the story that’s been handed down to us come from, when John didn’t say it, and Paul sure as hell didn't say it, and when everyone who actually worked with them made it clear it was a partnership of equals?

The answer is — not surprisingly — found in the fear of softness that we talked about at length in a prior episode. Because while John didn’t say any of that in so many words in his breakup interviews, and while he doesn’t seem to have had any conscious desire to wound Paul as deeply as he did, John’s creative insecurities are nonetheless deep and intense and persistent, and given everything pressing down on him at the time, it was probably inevitable he’d give in to them, if only subconsciously.

To understand what I mean, consider this example from an interview John gave in 1968 (edited for length) —

“I try not to get worked up about it, because it’s a waste of energy. I believe in conserving your energy. Why waste your time on it? There’s always going to be an Engelbert Humperdinck, and it doesn’t matter, y’know. I don't agree with the people that knock Engelbert singing “Street Fighting Man,” y’know. It’s a narrow concept of life... what’s wrong with the housewives and Engelbert Humperdinck? I don’t want to listen to it, I don’t want to hear it, I don’t want anything to do with it. But... I’m not such a snob as to denigrate the people that want to listen to that... Who is anybody to say that Engelbert Humperdinck isn’t as valid as anything else, y’know? Why go on about him and waste your energy? Just dig what you like, dig what you dig, and let other people dig what they dig.”30

And here he is again in 1970, in that infamous Rolling Stone interview with Jann Wenner—

“A couple of teachers would notice me, encourage me to be something or other, to draw or to paint — express myself. But most of the time they were trying to beat me into being a fuckin’ dentist or a teacher. And then the fuckin’ fans tried to beat me into being a fuckin’ Beatle or an Engelbert Humperdinck, and the critics tried to beat me into being Paul McCartney.”31

These are the quotes, along with a few others, that led to the widespread assumption that John explicitly compared Paul to middle-of-the-road ballader and crooner Engelbert Humperdinck. And that’s true — but it’s also not quite true.

If you look closely at what John said, he doesn’t compare Paul to Engelbert Humperdinck in so many words. He doesn’t even mention Paul in the first quote — they’re not even talking about Paul in that portion of the interview. John’s answer is a non sequitur to a question about whether he’s annoyed by pretentious films. And in the second quote to Rolling Stone, John explicitly separates being “beaten into being Engelbert Humperdinck” from being “beaten into being Paul McCartney.”

But of course, even though he’s not doing it explicitly, equating Paul to Engelbert Humperdinck is exactly what John is doing. There’s no other reason for John to bring up Engelbert Humperdinck in that context.32

In 1968 or ever, exactly no one is beating John into becoming Engelbert Humperdinck (or for that matter, Paul McCartney), and exactly no one then or now or ever has equated Engelbert Humperdinck with The Beatles or with John Lennon. This is utter and absolute bollocks from beginning to end — and John knows it, even through the fog of his heartbroken, insecure, gaslit, heroin-fueled brain.

And John would also know that Engelbert Humperdinck was — and maybe still is — a sore spot with Paul. While Paul has never said as much because it’s not something Paul would say, the comparison couldn't fail to be a sore spot, even beyond the obvious reasons.

Humperdinck’s big hit, “Release Me,” is the song that kept “Penny Lane” from reaching the #1 spot on the charts, making “Penny Lane” the first Beatles single not to reach #1 — and come to think of it, that’s also a reasonable omen for the collapse of the Sixties. And adding insult to injury, of course, “Penny Lane” was a double-A side along with “Strawberry Fields Forever” — which did reach #1. All of that almost certainly added to the sting for Paul, in John’s equating Paul to Humpderdinck. John almost certainly knew exactly what he was doing, when he reached for that comparison. He may even have reached for it based on private conversations in which Paul expressed to John his frustration relative to “Penny Lane” being kept out of the top spot by Humperdinck’s “Release Me.”

And because he’s John Lennon, master wordsmith who doesn’t stop being a master wordsmith just because he’s doing an interview rather than writing a lyric, he doesn’t need to make the equivalence directly. John knows full well people will get the reference to Paul, even if he doesn’t directly say it. And more than that, he knows Paul will get it.

And Paul did get it. Here’s Paul in 1974, when asked about his reaction to John’s Rolling Stone interview—

“I hated it. You can imagine, I sat down and pored over every little paragraph, every little sentence. “Does he really think that of me?” I thought. And at the time, I thought, “It’s me. I am. That’s just what I’m like. He’s captured me so well; I’m a turd, you know.” I sat down and really thought, I’m just nothin’. But then, well, kind of people who dug me like Linda said, “Now you know that’s not true, you’re joking. He’s got a grudge, man; the guy’s trying to polish you off.” Gradually I started to think, great, that’s not true. I’m not really like Engelbert; I don’t just write ballads. And that kept me kind of hanging on; but at the time, I tell you, it hurt me. Whew. Deep.”33

When we love someone, we know how to hurt them because we know them so well. Because those who love us also trust us with their vulnerabilities, and trust that we won’t turn around and use those vulnerabilities as weapons when things go wrong. And when we’re as intertwined and intimate with one another as John and Paul were, even more so.

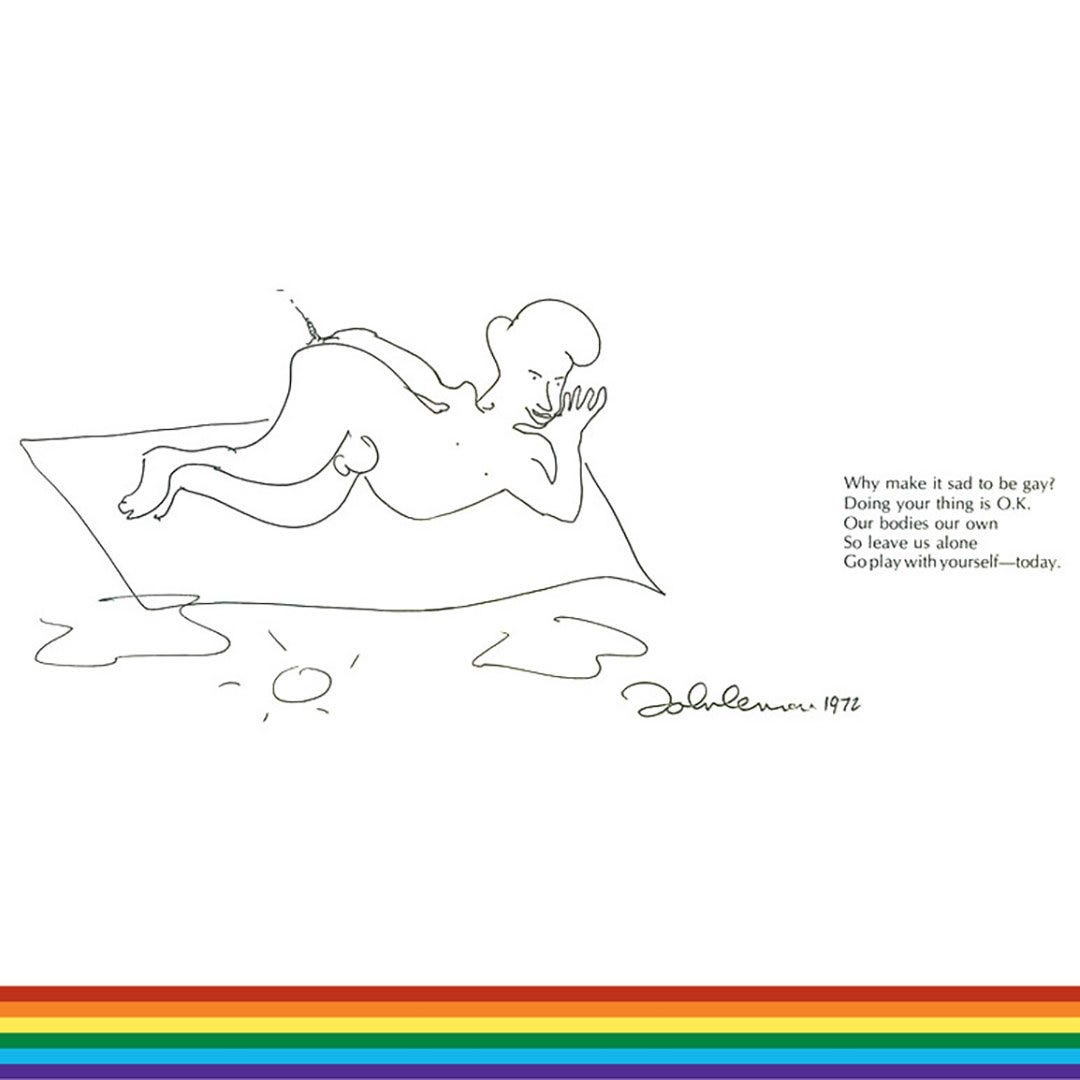

Here’s another example, also from the Rolling Stone interview. Wenner asks John about “Working Class Hero,” and John responds with, “I think its concept is revolutionary, and I hope it’s for workers and not for tarts and fags.”34

We’ll come back to the way John’s own internalized homophobia factored into all of this when we re-tell the story in the second part of the series, because there’s obviously a lot to notice about that.

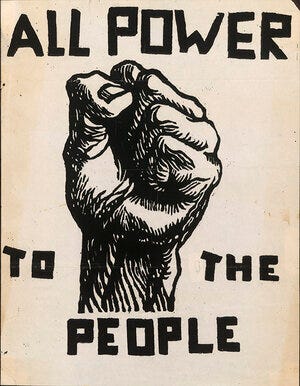

But for here, what matters relative to the “tarts and fags” quote is that John isn’t overtly saying that Paul’s music — or the music of The Beatles — is for “tarts and fags,” but he’s sure as hell implying it. And more than that, by saying his music is for “workers,” he’s invoking the classic rugged image of the worker, which at the time was entangled with the clenched fist of the Communist worker’s movement that John was involved with during this period.

Brick by subversive brick, in veiled innuendo and indirect reference, as only a master wordsmith skilled in subtext and double meaning can — and fueled by his insecurity and his broken heart — John constructs his distorted ‘John vs Paul’ narrative.

With a single exception that we’ll talk about in a future episode, John never denigrates Paul’s talent — in the Rolling Stone interview, he calls Paul a “fucking brilliant songwriter.”35 And he never says he doesn’t love Paul. As we saw in episode 1:2, quite the opposite.

What John does instead is to separate out his music from Paul’s by claiming they never wrote together, which in turn splits Lennon/McCartney into ‘John songs’ and ‘Paul songs.’ And having done that, he then draws draw a sharp line between his music and Paul’s, calling Paul’s music “granny music”36 and “light and easy,”37 and “jog-along happy songs,”38 and making it clear that he, John, wants nothing to do with that kind of— are you seeing it?

Softness.

Aided and abetted by “How Do You Sleep?” and some questionable musical choices by Paul — most notably releasing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” as a single39 — John used his Breakup Tour to build himself up as the angry, edgy, uncompromising, gimme some truth working class hero unafraid to say “fuck you” to the Establishment, while simultaneously positioning Paul as the mild-mannered, “living with straights,” sweater-vest wearing conventional ballad-writing pop star with the conventional wife, the conventional life, and also a lot of fluffy... soft... sheep.

The breakup narrative John offered to the world’s press was stark and clear, and as we’ll see, very, very tempting to those journalists — John was “hard” and Paul was “soft.”

And that’s how ‘John vs. Paul’ became ‘John/hard vs. Paul/soft.’

Before we de-bunk this duality, I want to say that I’m uncomfortable even having to de-bunk it — because doing so implies that there’s something inherently wrong with being “soft” and that Paul therefore needs to be defended for it by pointing out all of the ways in which he is not, in fact, soft. That is, in and of itself, fallout from the fear of softness — because no one in our culture is immune to its insidious and poisonous effects, including me.

But putting aside the larger problem that there is nothing at all wrong with “soft” —musically, or otherwise — there is, of course, no justification for this musical duality.

We’ll talk more about hard vs soft in terms of their relationship in a bit, but let’s just say here what many others before me have already said, though it doesn't seem to be getting through, so it’s worth saying again—

Musically, Paul McCartney is responsible for the hardest, most aggressive music in The Beatles’ catalogue — songs like “I’m Down” “Back in the USSR,” “Birthday” “Got To Get You Into My Life,” and of course, “Helter Skelter,” widely acknowledged as the first heavy metal song. And then there’s Paul’s blistering guitar solo on “Taxman,” and his throat-shredding vocals on “Long Tall Sally,” “Kansas City,” “Hippie Hippie Shake,” “Ooh My Soul” and “Oh! Darling.” And that’s not even counting his solo work.40

Conversely, John is responsible for some of the softest, most poignant songs in the Beatles catalogue — songs like “It’s Only Love,” “Julia,” “Dear Prudence,” “Across The Universe,” and “Goodnight,” the big band-style instrumental that closes The White Album, not to mention solo work like “Love” “You Are Here” and “Beautiful Boy.”41 And then there’s “Mother,” raw, deeply vulnerable and consisting of little other than John explicitly crying out for his mother — and while in Western culture, a grown man publicly crying for his mother is inarguably brave, that’s mainly because it’s the very definition of “soft.”4243

More than that, though — and this is something that I’ve not seen pointed out — I’m hard-pressed to think of many “hard” ‘John songs’ at all during The Beatles years, other than “Yer Blues,” the faster version of “Revolution,” and “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” and all of those were very late in their catalogue. On the other hand, Paul has consistently released both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ music both through the Beatles’ years and in his solo work, whereas the vast majority of what John has released through the years has been anything but ‘hard.’

The journalists who interviewed John didn’t let these facts get in their way, though — and apparently they still don’t — because confirmation bias means we see what we expect and want to see rather than what’s really there. And that takes us back to why journalists were so eager to believe John’s version of events and to take his side in the breakup — and in the ‘John vs Paul’ split.

This soft/hard split between Paul and John wasn’t in and of itself new. It had appeared as early as 1966 in an unpublished Newsweek interview.44 But before the breakup, it wasn’t said pejoratively. And more than that, because John and Paul had always shared equal credit for all of their songs, it didn't split them into a duality. It didn’t force anyone to choose one or the other. It was understood that the combination of both hard and soft is part of the magick that made The Beatles what they were and are. And as we talked about in a prior episode, the dance of hard and soft was — and is — at the heart of the ineffable magick of Lennon/McCartney.

The press used to get that, before ‘John vs. Paul.’ But John’s breakup narrative — telling the world that he and Paul never wrote together, splitting Lennon/McCartney into ‘John vs Paul,’ and then styling himself as hard and Paul as soft — changed all of that.

“In the Beatles subculture,” wrote biographer Philip Norman of “immovable heterosexuality” and “they only had a professional relationship” fame, “one inevitably finds oneself tagged either as a ‘John’ person or a ‘Paul’ person. I cannot pretend to be other than the former.”45

Norman makes this comment as if ‘John vs. Paul’ followed some sort of immutable law of nature, rather than being a division that — as we’ll see in the next episode — he himself was a primary architect in creating. But as Grail-phobic as Norman’s comment is, it’s also, unfortunately true.

The breakup of The Beatles was the very definition of a bad breakup. And in any bad breakup, people who had previously been loyal to the couple as a couple invariably choose sides. And not surprisingly, the vast majority of journalists and biographers chose (and continue to choose) John’s side — because virtually all journalists during that era were men, and more than that, men who identified strongly with John.

Some of that identification was, of course, because of the perception of John as the leader of the band, and the cultural tendency for men, and especially men identified with “might makes right” — which in our culture is most men — to identify with the hierarchical leader of any group.

But the deeper reason for that identification — not unrelated to John being perceived as the leader — is almost certainly that same fear of softness that stripped the lovers possibility out of the story — the fear of the lifeforce love of the Grail that had sparked and fueled the Love Revolution.

And so began the deeper, more specific wounding in the story.

What happened next isn't mythological, it's just ordinary. It's just how humans work. And fundamentally and in the end, that's what mythology is and why it shapes our world and our lives — it’s the deeper explanation for how humans work and why we do what we do.

We try to be like the people we admire. We follow the patterns set out for us by our role models — consciously, subconsciously. We take our lessons for how the world works from them and who we want to be in that world and how we interact with it — and especially so, if those role models are mythological figures who created a new world and shaped our identity in the process.

And because journalists identified with John — and more than that, because their fear of softness meant they wanted to be on the “hard” side of the breakup — they ignored John’s retractions and the evidence of their eyes and ears and hearts, and instead chose to believe John’s hard, angry breakup narrative.

And when journalists sided with John in his narrative of ‘John/hard vs. Paul/soft,’ they twisted the story of The Beatles — of Lennon/McCartney — from a story of joyful, intimate, loving creative partnership into a story of two rival artists locked in mortal combat for A-sides and creative control, in the studio and in courtrooms and in the court of public opinion.

When we shift a story — any story — from partnership and collaboration into competition and rivalry, we change it from a story of equals to a story of more and less, because by definition, competition means someone has to be “less” so that someone else can be “more.”

And when we fear something, we often deal with that fear by diminishing the value of what we fear. For men in particular, the “might makes right” hardness of John’s version of the story felt — and still feels — safer because it’s familiar. It’s rooted in those old ideas of what it meant to be a man — because for two thousand years, up until the Love Revolution, that’s what it had always been.

And so inevitably, John became ‘more’ and Paul became ‘less.’ And the duality became not just ‘John vs. Paul’ or even ‘John/hard vs. Paul/soft,’ but ‘John/more vs Paul/less.’ Which in mythological terms, becomes ‘hard/more vs soft/less.’ The Lance over the Grail — or more accurately, the fear of the Grail over the Grail. And just like it did for the two thousand years prior to the Love Revolution, ‘hard/more vs. soft/less’ has shaped the story of The Beatles — and as we’re about to see, our world and all of our lives — ever since.

The tragedy of all of this — well, one of the many — is that, even beyond the music, this is an entirely false duality.

Anyone who thinks Paul McCartney doesn't have multiple bands of steel running through his character hasn’t been paying attention for the past 60 years, and we’ll talk about that in the next episode. And as for the “hard” John Lennon that journalists — and John himself — was willing to sacrifice the more truthful and beautiful story to protect?

That John doesn’t even exist.

“I’ve always thought that the real truth of The Beatles could be found in shades of grey, but most people find it easier to deal in the black and white of it all.”46 — Paul McCartney

Back in the earliest days of my research, I came across a comment on a prominent Beatles website about John’s “uber-masculinity.” Even before having considered any of this in earnest, I remember being confused by this description of John, and even more confused that no one challenged it — because of all the qualities we could apply to John Lennon (or any of the Fabs), “uber-masculinity” doesn’t seem to be one of them.

I mean, yes, the man could inhabit a black leather jacket like nobody’s business, but the debunking of John’s supposed “uber-masculinity” is easily found in his own words in one of his last interviews in 1980. It’s a long quote but worth reading unedited in its entirety—

“I come from the macho school of pretense. I was never really a street kid or a tough guy. I used to dress like a Teddy boy and identify with Marlon Brando and Elvis Presley, but I never really was in real street fights or real down-home gangs. I was just a suburban kid, imitating the rockers. But it was a big part of one’s life to look tough. I spent the whole of my childhood with shoulders up around the top of me head and me glasses off because glasses were sissy, and walking in complete fear, but with the toughest-looking face you’ve ever seen. I’d get into trouble just because of the way I looked.

I wanted to be this tough James Dean all the time. It took a lot of wrestling to stop doing that, even though I still fall into it when I get insecure and nervous. I still drop into that I’m-a-street-kid stance, but I have to keep remembering that I never really was one. I was torn between being Marlon Brando and being the sensitive poet — the Oscar Wilde part of me with the velvet, feminine side. I was always torn between the two, mainly opting for the macho side, because if you showed the other side, you were dead.”47

And here’s John again, also in 1980 —

“I’m still a bit feeling that I’m supposed to be macho, Butch Cassidy or something and tough Lennon with the leather jacket, and swearing and all that.... (sic) and I really am just as romantic as the next guy, you know, and I always was.”48

In a 1980 interview for RKO Radio, John also acknowledged — not for the first time — that his whole “I can’t stand Paul’s granny music” schtick during the breakup was BS. He starts by saying, “You see, that was the thing about The Beatles — they never stuck to one style. Just blues or just rock. We loved all music. And I still do. I mean I can get off on—”

Here the interviewer, apparently alarmed that John might be about to say something that counters the breakup narrative, interrupts him and finishes his sentence for him by saying— “You’re rock and roll.”

Interviewers did a lot of that kind of thing with John, trying to keep him to the “hard” breakup narrative. And a lot of the time it worked. But this time, instead of going along with it, John corrects him with—

“I got that image, but when you think I did ‘In My Life,’ ‘Anna,’ on the early things, and lots of ballady things, you know? It’s just, my image was more rocky, you know? But if you look down those Beatle tracks I’m right there with all the sentimental – just the same as Paul or anybody else. I love that music just as much.”49

As we know, John is often and by his own admission an unreliable narrator, but I think we can take him at his word when he says his uber-masculine image was just posturing, because I don’t think he has any reason to lie about this. Quite the contrary — in our hard, Lance-obsessed culture, he has far more to gain by continuing to posture as uber-masculine than he does by admitting that it was all an act.

It’s not at all surprising that John would have cultivated exaggerated, performative masculinity — but probably not because, as he claims, it was necessary to survive. He wasn’t exactly living on the hardscrabble streets of Liverpool — remember what he said in the quote we just looked at, about how he was a suburban kid imitating the rockers and not someone who engaged in street fighting. And clearly Paul, George and Ringo didn’t feel the need to perform exaggerated masculinity in their teenage years, and their upbringing was rougher than John’s.

But that kind of posturing is a common defense mechanism for covering up the sorts of things John in particular felt needed covering up — his vulnerability, his insecurity, his fear of being abandoned and rejected, his intuitive sensitivity to art and literature and, of course, to music, and yes, almost certainly his by-now-well-documented attraction to men.

Don’t take my word for all of that, though. Here’s Motörhead’s Lemmy Kilmister, who saw the pre-fame Beatles play at the Cavern in 1962—

“I remember one gig the Beatles had at the Cavern. It was just after they got Brian Epstein as their manager. Everyone in Liverpool knew that Epstein was gay, and some kid in the audience screamed, 'John Lennon's a fucking queer!' And John—who never wore his glasses on stage—put his guitar down and went into the crowd, shouting, 'Who said that?' So this kid says, 'I fucking did.' John went after him and BAM, gave him the Liverpool kiss, sticking the nut on him—twice! And the kid went down in a mass of blood, snot and teeth. Then John got back on the stage.

'Anybody else?' he asked. Silence. 'All right then. ‘Some Other Guy’."50

Again, there’s no real reason to doubt the truth of this story, particularly since it matches up with other similar stories from John's early days, including the infamous incident at Paul’s 21st birthday party when John assaulted Cavern compère Bob Wooler for suggesting that John’s vacation to Spain with Brian was more than platonic in nature.

And I probably don’t need to point out that this kind of the aggressive, outwards expression of internalized homophobia — which is, remember, a phobia, a fear — is a literal trope when it comes to covering up both softness, and fear of softness.

Paul may well have known John better than anyone else ever did — remember that Paul, along with Brian, is the only one who had enough of an intuitive sense of John’s emotional cues that he could soften John’s suit of armour and temper his volatility. And so of course Paul recognised John’s faux-masculinity as posturing. You might remember a quote from Paul that we considered in a prior episode in another context—

“One of my great memories of John is from when we were having some argument. I was disagreeing and we were calling each other names. We let it settle for a second and then he lowered his glasses and he said: “It’s only me.” And then he put his glasses back on again. To me, that was John. Those were the moments when I actually saw him without the facade, the armour, which I loved as well, like anyone else. It was a beautiful suit of armour. But it was wonderful when he let the visor down and you’d just see the John Lennon that he was frightened to reveal to the world.”51

In his more self-aware moments, as in John’s ‘Oscar Wilde versus Marlon Brando’ quote from earlier, John understood even as a teenager that his faux masculinity wasn’t authentic or healthy. It’s what he was acknowledging, when he acknowledged feeling trapped between needing to appear tough to feel safe, while longing to embrace his inner ‘velvet poet’— by his own account, the truer part of himself.

Paul seems to have been one of the only people, at least in those early days, who got to see the ‘velvet poet’ side of John. Here’s Paul again in 1997—

“The acerbic John is the one we know and love, you know, because he was clever with it, so it was very attractive. But for me, I have more than a slight affection for the John that I knew then, when we were first writing songs, when we would try and do things the old songwriters had done. I slightly regret the way John's image has formed, and because he died so tragically it has become set in concrete. The acerbic side was there but it was only part of him. He was also such a sweet, lovely man – a really sweet guy.”52

And later in Many Years From Now, Paul talks about John’s song “Goodnight” that closes The White Album—

“We heard him sing it in order to teach it to Ringo and he sang it very tenderly. John rarely showed his tender side, but my key memories of John are when he was tender, that's what has remained with me; those moments where he showed himself to be a very generous, loving person. I always cite [‘Goodnight’] as an example of the John beneath the surface that we only saw occasionally. I think that was what made us love John,53 otherwise he could be unbearable and he could be quite cruel. Now that I'm older, I realise that his hostility was a cover-up for the vulnerability that he felt, and if you look at his family history it's easy to see why. But this is an example of that tender side.”54

We can get literal here, too. Here’s Pauline Lennon, John’s biological father’s wife, describing her first meeting with John in 196855—

“My first sight of John as he entered the room certainly destroyed my preconceptions of the man. He appeared much more delicate and gentle than the solidly tough, macho image he projected on stage. Tall and surprisingly narrow-framed, he walked with an almost mincing shuffle — always in his stockinged feet — and it immediately struck me that there was something rather feminine about him when he was relaxed.”56

I’m not offering any of this to feminize John or to make him one-dimensional. Quite the contrary. The point here is that at best, the perception of John as “uber-masculine” is oversimplified and incomplete. At worst, it’s deeply unhealthy.

Here’s Paul in 1997 commenting on the complexity of the hard/soft dynamic between them (edited for length) —

“People always assume that John was the hard-edged one and I was the soft-edged one, so much so that over the years I've come to accept that. But... I can bite, I certainly have a hard side... John, because of his upbringing and his unstable family life, had to be hard... But we wouldn't have put up with each other had we each only had that surface. I often used to boss him round, and he must have appreciated the hard side in me or it wouldn't have worked; conversely, I very much appreciated the soft side in him. It was a four-cornered thing rather than two-cornered, it had diagonals and my hard side could talk to John's hard side when it was necessary, and our soft edges talked to each other.”57

And later in the same passage —

“John was more introverted and much more willing to hurt someone in order to try and save his own neck, but this had never been a requirement for me, except running away from guys who would hit you physically... John had a lot to guard against, and it formed his personality; he was a very guarded person. I think that was the balance between us: John was caustic and witty out of necessity and, underneath, quite a warm character when you got to know him. I was the opposite, easy-going, friendly, no necessity to be caustic or biting or acerbic but I could be tough if I needed to be.”58

But despite John’s (and Paul’s) words to the contrary and the evidence of our eyes and ears, and John himself telling us it was mostly an act, it’s the cocky, posturing Teddy Boy image — the black leather and the sneer and the arrogant swagger, the accounts of bar fights and drinking to excess, and later, the raised fist of the angry, bitter revolutionary — that for many men still sticks as the thing to admire, because that’s our culture’s one-dimensional definition of a “real man.”

And unfortunately, the attraction to faux-masculinity isn’t limited to men. This is also the masculinity many women have been taught to respond to, because women have been taught that same one-dimensional view of what a man is.

There’s a striking example of this from at-the-time celebrity psychologist Dr. Joyce Brothers, who in 1964, was asked to explain Beatlemania. She begins by saying—

“The Beatles display a few mannerisms that almost seem a shade on the feminine side, such as the tossing of their long manes of hair. These are exactly the mannerisms that very young female fans (in the 10-to-14-year-old age group) appear to go wildest over. No doubt many of their mothers have wondered why.”

So far so sort-of-fine, but then she offers her “explanation”—

“Girls in very early adolescence still in truth find “soft” or “girlish” characteristics more attractive than rigidly masculine men. They get crushes on their female school teachers, and on slightly older girls. The male movie stars they most admire are apt to be the “pretty boys” their big sisters would dismiss as kid stuff. I think the explanation may be that these very young “women” are still a little frightened of the idea of sex. Therefore, they feel safer worshipping idols who don’t seem too masculine, or too much the he-man.”59

Putting aside her Grail-blind dismissal of the global spiritual awakening of Beatlemania as nothing more than a mass pre-teen crush on a cute boy band, so many things about this passage are heartbreaking. The conflation of “soft” with “girlish,” the assertion that there’s something immature about responding to that softness in a man (when the opposite is far more true), and the implication that it’s natural and desirable for a girl to grow up and shift attraction away from healthy masculinity to “rigid masculinity.”60

There are many reasons to idolise John Lennon, but his supposed “uber-masculinity” isn’t one of them — except maybe insofar as it was evidence of his stubborn ability to survive the pain of his childhood.

But ultimately, as the breakup and its aftermath shows all too well, John’s posturing didn’t do much other than hurt those around him — and perhaps himself most of all.

In addition to causing all the problems it caused with the people in his life who loved him and were hurt by his posturing — most of all, of course, Paul — the insistence on seeing John as “uber-masculine” forces him into the same one-dimensional model of masculinity that he felt trapped in as a teenager, and, as he remarked on in 1980, throughout his life as an adult. It denies him the right to be remembered as a more fully formed human being.

Far better to idolise John Lennon for his struggle — not always successful and sometimes spectacularly unsuccessful — to transcend the culturally restrictive model of masculinity that he felt trapped in for most of his life. Because the fixation on John as a faux-masculine figure prevents us from understanding both John as a person and John as the complex, sensitive, Grail-fluent, receptive to love and inspiration creative genius that the writer of “Strawberry Fields Forever” by necessity was.

As with so many men (and increasingly women), fear of softness tricked John into pretending to be something he wasn’t — even during his Breakup Tour when he reverted to his hard, angry pre-Beatles defence mechanisms. And that same fear of softness tricked many men into thinking John’s performed “uber-masculinity” was the real thing, and that it was worth emulating. And that’s almost certainly the deeper reason those (again, mostly male) journalists were so eager to believe the ‘John/hard vs. Paul/soft’ narrative.

All of this is why Paul came out of the breakup carrying the stigma of softness without the Lance, while John carries the cultural credibility of hardness without the Grail — and why to this day, there are a lot of people who still believe this. And more than believe it, who continue to aggressively advance that toxic narrative. ‘John vs. Paul.’ ‘John/hard vs. Paul/soft.’ ‘John/more vs. Paul/less.’

There are no fewer than four levels of fiction in ‘John vs Paul.’ That John and Paul mostly wrote separately is a fiction — as we talked about in a prior Rabbit Hole. That John and Paul only had a professional relationship, which we’ve spent these past three episodes de-bunking. That John is hard and Paul is soft, which we just saw isn’t true. And that John is more and Paul is less — which is self-evident nonsense, and we’ll deal more with that last one in the next episode.

Confirmation bias. We see what we expect — and often what we want — to see and ignore the rest.

It would be a profound act of Sixties countercultural transgressive courage to get over all of this ‘John/hard vs Paul/soft’ insanity, given the truer, more beautiful and more complete story waiting to be reclaimed on the other side of it.

Just as the reward for paying attention to the Grail is the combined power of the Lance and the Grail, together John and Paul represent the yin/yang of hard and soft, each contained in the other, intertwined in an ever-shifting complex dance not unlike their ever-shifting harmonies in “If I Fell.” Together, John and Paul are the template for a new man — but more accurately, a whole man — and a new, and better, world.

The act of creation, like the act of making love, requires vulnerability and receptivity — other words for softness. We can’t truly partner with someone in an intimate relationship — creative or romantic or otherwise — if we’re busy putting up armour so no one can get in.

It seems likely that The Beatles happened only because the love — and thus the intimacy and trust — between John and Paul, but also between the four of them — softened John’s faux masculinity enough to make possible a long-term creative (and possibly romantic) relationship with Paul.61 Artists have to be this kind of soft if they’re going to create art that means anything at all.

But as with most things about this story, it’s not either/or. Not when it comes to John, and not when it comes to Paul.

If soft is all an artist is, then there’s not enough drive to get that art into the world (which is probably why most artists don’t get their art into the world). You certainly don’t reach the toppermost of the poppermost on softness alone. It’s just that without softness, there’s not a lot of point in getting to the toppermost, because you have nothing of lasting value to offer if you do.

This series focuses on John and Paul, but we could easily say similar things, relative to soft and hard, about George and Ringo — not that they were lovers (presumably), but that they modeled the same new kind of masculinity that reaches for a more mature definition of what it means to be a man — but, really, what it means to be a human.

And that takes us back to our story about the story — and to the wounding in that story that’s still bleeding out into our world.

“It was the Beatles who taught me to hug other men.”62 — Derek Taylor

As we’ve talked about at length in earlier episodes, by the time the Sixties arrived, the world had suffered the devastation of two World Wars of unprecedented scale and destruction, as well as the horrors of the Holocaust and the dropping of the atomic bomb. By 1963, virtually everyone on the planet was suffering from the most prolonged and widespread death trauma the world had ever experienced. And without doubt, that death trauma was caused by “might makes right,” the abusive parent of “suffer now, rewards later.” And “might makes right,” you can perhaps see immediately, is the defining story of hard, one-dimensional uber — but really faux — masculine power.

Here’s John in 1980—

“I know it’s almost the same in America, but male children in England were brought up to defend the country. I mean, that was about it, you know? You had to have discipline and not touch the kid. He had to be hard… (sic) a boy was really programmed to go into the army, that was about it, you know. And you had to be tough and you’re not supposed to cry and you’re not supposed to show emotion. And I know Americans show more emotion, they’re more open than English people, but it’s pretty similar over here. There’s that Calvinist Protestant Anglo-Saxon ethic which is, ‘don’t touch, don’t react, don’t feel’ And I think that’s what screwed us all up. And I think it’s time for a change.”63

The infusion of erotic lifeforce love during Beatlemania — sparked and fueled by the love between John and Paul at the centre of it — had gone a long way towards healing this global post-war death trauma. But if the world was going to find a way out of the relentless destruction of the first half of the twentieth century, the new generation of men needed to find their way out of the scourge of “might makes right” masculinity and into something healthier. Young men needed to find the courage to be willing to defy cultural expectations and learn the softer power of the Grail.

Men had experimented with Grail softness before, of course — the ecstatic mystery cults of the ancient world, the early gnostic Christians, the Romantic poets, the Transcendentalists of nineteenth century New England, and the medieval troubadours who spread the Grail tradition throughout Europe, to name just a few examples. But like the social and artistic movements prior to the Sixties that had pushed against “suffer now, rewards later,” men’s interest in the Grail had never before manifested itself in large enough numbers to make any meaningful difference in what the culture expected and allowed a man to be — and certainly never with enough impact to change the mythology and trajectory of the whole of Western civilization.

The Sixties was different. While the ‘70s would be the decade when a new generation of women claimed the hardness of the Lance, the Sixties was the first time a new generation of men claimed — albeit temporarily— the softness of the Grail — which remember, is not weakness, but the missing receptivity to emotion that’s required to be a whole man — or in the Grail legend, a king.

And most of those men began that journey, directly or indirectly, by following the example set by The Beatles.

It’s challenging to articulate what specifically it was about The Beatles that people recognised as a new kind of masculinity. History tends to focus on the long-for-the-time hair and what we might now call ‘metrosexual’ designer suits, because those things are the most visible. But it takes more than a haircut and fashionable clothes to define masculinity, despite what the Madison Avenue mad men would have us believe.

I suspect the majority of it was sensing the transgressive lifeforce love between John and Paul, but that was probably picked up on more by the girls than by the boys. And The Fabs certainly weren’t effeminate — that would have been their death-knell before they even got started, for sure early on in Liverpool and Hamburg, and later in the world at large.

Certainly that new model of masculinity included the love and affection between the four of them, the collaborative nature of their creative process, and the emphasis on love in their music. “Our songs were always about peace and freedom and love,” John once told Beatles press agent Derek Taylor. “There was never any other message.”64

But of course, it was even more than all of that. In the 2024 documentary Beatles ‘64, feminist writer Betty Friedan did a beautiful job of articulating the new masculinity The Beatles were offering to men (edited for length) —

“These boys that are wearing their hair long are saying, "No, I don't have to be all that, crew-cut and tight-lipped. I don't have to be dominant and superior to anyone... I don't have to kill anybody to prove anything. I can be tender, and I can be sensitive, and I can be compassionate. And I can admit sometimes that I'm afraid, and I can even cry. And I am a man. I am my own man. And that man, who is strong enough to be gentle, that is a new man.”65

And here’s John in 1980—

“Isn’t it time we destroyed [the conventional view of masculinity] because where has it gotten us after all these thousands of years? Are we still gonna be clubbing each other to death? Do I have to arm wrestle you to have a relationship with you as another male? Do I have to seduce her or come on with her, that I’m gonna lay her because she’s a female, or come on as some sexual. . . . (sic) Can we not have a relationship on some other level besides that same old stuff all the time? I mean, it’s kids’ stuff, man; it’s really kids’ stuff. And I don’t wanna go through life pretendin’ to be James Dean or Marlon Brando, you know? In a movie—not in real life, even—in a movie version of them.”66