All the episodes of Beautiful Possibility in sequence are here.

This episode works pretty well on its own, but obviously since it’s part 2, it works better if you’ve read/listened to part 1 first. You’ll also have a fuller and more beautiful experience of this episode if you’ve listened to the Rabbit Hole: “The ‘entangled form’ of Lennon/McCartney.

Hi everyone,

Before we get to the main episode, I want to take just a couple of minutes for a few housekeeping notes. And I also want to talk with you — briefly — about Ian Leslie’s book, before we continue with part 2 of “He Said He Said.”

Housekeeping first.

If you joined midway through, you’ll get the most out of Beautiful Possibility by starting from the beginning — but if you’re not doing that, I’ve added notes at the top of every episode about what you’d want to listen to or read to get the most out of that episode.

Second, after this episode, I’m going to slow the release rate of new material to once a week, alternating between Rabbit Holes and episodes, to give all of us — including me — the chance to get caught up.

Before we get to this week’s episode, I want to talk just for a few minutes especially to those of you in the Beatles studies counterculture — what y’all might call the “JohnandPaul world” — about Ian Leslie’s book. And to do it we’ll need to borrow just a tiny bit from the final episode of part one. If you’re not interested in this part, obviously please feel free to scroll down a bit to the main episode.

Okay, then.

As much as I respect and support the Beatles studies counterculture, I’m also very aware that I'm not really part of that world. As I mentioned in a prior episode, as a Beatles scholar, I have one foot in the mainstream and one foot in the counterculture and I have a bumpy relationship with both. So I may be talking out of turn in what I want to say here. But sometimes standing between worlds and being part of neither allows a perspective of both sides that isn’t available otherwise. So I hope those of you who are part of the “JohnandPaul” world will accept the following with the love with which it’s intended.

I know many of you are disappointed and frustrated by

’s book. I was disappointed and frustrated, too, when I read an advance copy of it back in December.I know the misleading title and the promotional hype made it seem like it was going to be — finally — something different from the same old Grail-phobic, fear of softness false narrative of every other Beatles book. And I know it was frustrating and disappointing to discover it’s mostly a lightweight version of the same old distorted breakup narrative dressed up in the deceptively prettier package of the title and Leslie’s “discovery” of the shocking truth that John and Paul didn’t actually hate one another.

The most troubling part of it is, of course, that Leslie’s book once again hurts John and Paul by misunderstanding and trivializing their relationship. I mean, I love my dog, too, more than I love most people, but equating Paul's love for John with his love for Martha is maybe the most creative and bizarre way so far of pretzel-twisting to avoid the lovers possibility — and that’s saying something, given all the pretzel-twisting we’ve already seen in that regard.1

Like many of you, I feel all of that frustration and disappointment. But to offer some perspective, Ian Leslie is a good writer. His prose is quite beautiful, especially in the passages where he describes the music. And writing this story more beautifully is also part of healing the story.

And while it’s not what many of us hoped for when it comes to the lovers possibility, Leslie is not entirely illiterate in the softer language of the Grail. And regardless of its content, that a published book with the words “love story” and “John and Paul” is in the world is a vast improvement over what’s come before. It’s a sign that despite the resistance, the story is changing for the better.

And while Leslie completely misreads his own research and does the usual Grail-phobic and nonsensical “they weren’t lovers” thing at the end of his book — and again, how could he possibly know that? — it’s still true that if people who are absolutely opposed to the idea that John and Paul even liked each other read his book (because you know those people will not be listening to Beautiful Possibility) and soften their relationship to the story just a little bit, that's work worth doing. And that makes Ian Leslie's book worth having in the world.

What's more important is that situations like Leslie’s book are going to keep happening, as long as the best research and analysis and writing being done on The Beatles is being done by people who publish anonymously in places nobody can find on platforms that aren’t credible.

As we talked about in episode three, as long as all of that is hidden away in the counterculture, of course people will occasionally stumble in, grab hold of bits and pieces of what they find, misunderstand what they’ve found because they’re not Grail-fluent, write daft articles and books like Leslie’s, and then take credit for it as if they’ve discovered something new. It’s similar to Columbus “discovering” America, when the people who were already there are like, uh... hello?

Again, we’re getting ahead of ourselves, and we’ll talk about this better in the final episode of part one, but—

No one from the Beatles mainstream is coming to save this story — this foundational myth of our modern world. The blind will not suddenly see. We know — and by we, I mean the Beatles studies countercuture — that whether John and Paul acted on their love for one another or not, the story of The Beatles is at its heart, a love story. And as long as the only people willing to write publicly about them are people who are afraid of love, this is never going to change.

If we want the truer and more beautiful story of John and Paul, and of The Beatles, in the world, we're going to have to put it there — and by we I mean those of us who do see the actual love at the heart of this story — because the fear of softness among old-school Beatles writers that we talked about in episode 1:4 is a real and powerful thing. And also because those old school writers have a lot vested in the false narrative, and we don’t live in a culture where people — especially men — are allowed to say they’re wrong without being accused of being, well... soft. That, too, as we’ll see in a future episode, is collateral damage from the breakup narrative.

We're not going to be able to heal the story by reclaiming it from the false breakup narrative by just wringing our hands and feeling frustrated. If you’re frustrated and disappointed with Ian Leslie’s book, I encourage you to come out from under the cloak of anonymity and share your work legitimately, under your actual names with the serious professional credentials that I know for a fact many of you possess, and in places where people can find it, and more than that, in places where people who find it will take it seriously

I don’t know if you noticed, but I’m publishing this under my own name on a public platform. And I’ve never been anything other than open with my very conservative corporate clients about the nature of my work, and it’s never once been a problem. In fact, several of them are reading and enjoying Beautiful Possibility. The world has not ended. Everything is fine — at least so far — with regard to publicly writing the lovers possibility.

But it will take more than just Beautiful Possibility to lift this story out of the false and toxic breakup narrative, just as it took more than The Beatles to make the Love Revolution happen.

I can think of at least half a dozen Beatles countercultural scholars who are writing the lovers possibility and who would write amazing substacks that would make a real difference in reclaiming this story from the fearful, angry breakup narrative. If you're one of them and you start a substack — under your own name and citing your professional credentials, as I have — I’ll share it on The Abbey. That’s how we start a movement. That’s how we change the story.

Speak your truth even though your voice shakes. This story, this music, the world-changing love between John and Paul is worth it.

And If you’re still worried about the ethics of doing this, I get that. Just hang on a bit longer with me — we’re still working on laying the foundation to talk about how we can talk about it without stepping on John and Paul's right to tell their own story, and we’re almost there.

As for Ian Leslie…

Ian... honey... as my actual Texas grandma never said, you’ve got yourself on the wrong side of the deep end with all of this. You are so far out of your league here, especially if you’re going to use “love” in your book title. Take a seat, and let me show you how to interpret the art... and the love... of Lennon/McCartney.

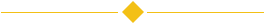

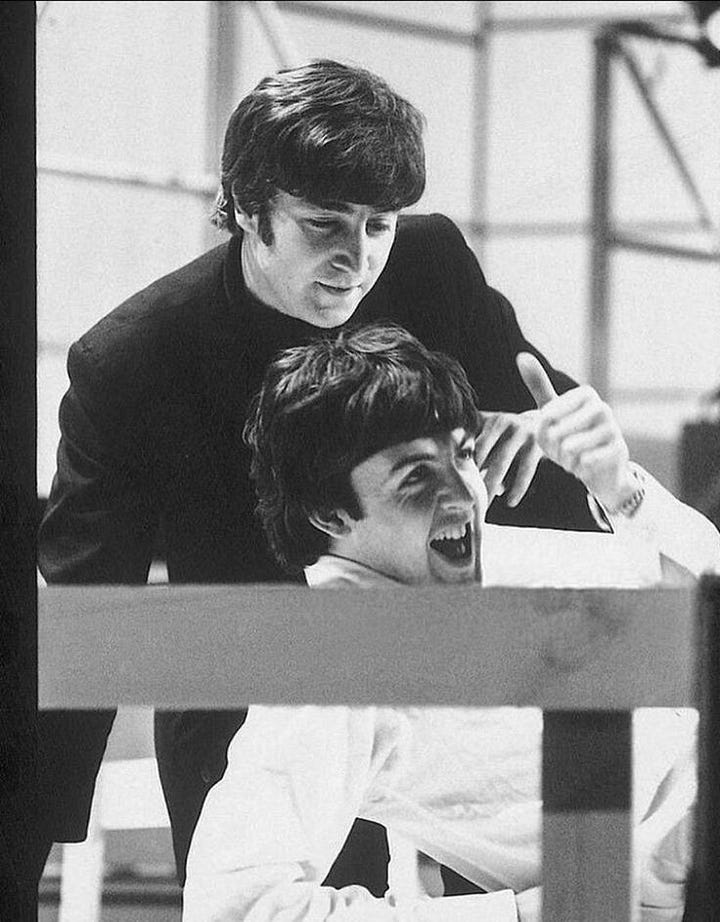

The Pyramus and Thisbe pantomime that the Beatles performed in 1964 is usually thought of as either a quirky comedic part of their story, or as an example of the kind of degrading publicity stunt that performers of a prior era were forced into during a time when they were considered vaudeville-style “entertainers” rather than serious artists.

I suspect the sketch, no doubt instigated at manager Brian Epstein’s recommendation, is an example of what all four of them, but perhaps especially John and George, despised about the “mop top” era, and it’s hard to fault them in this. However much that sort of thing was part of the “trojan horse” subversion of Brian’s respectability makeover, The Beatles must have felt ridiculous participating in this sort of vaudevillian schtick — world-class artists leading a world-changing cultural revolution, but compelled by Brian’s outdated theatrical sensibilities and the customs of a prior generation to dress in silly costumes and shill for laughs like a third-rate comedy troupe.2

I wonder, though, if it’s a bit more than that.

A lot of people in the mainstream Beatles world see John and Paul playing lovers onstage as amusing — how funny, to see Paul and John dressed in silly costumes pretending to be lovers. And a lot of people in the Beatles studies counterculture see John and Paul playing lovers onstage as romantic, and especially given the parallel of Pyramus and Thisbe as lovers kept apart by cultural disapproval.

But for me, watching the Pyramus and Thisbe skit is deeply uncomfortable and not at all amusing or romantic. Because in light of the lovers possibility, I can’t help but wonder if performing it might have been especially painful for Paul and John in ways the other indignities Brian foisted on them weren’t.

When years after, Paul named that pair of kittens Pyramus and Thisbe, maybe it was a happy reminder of a happy memory. Or maybe it was a bittersweet reminder of the one and only time he and John had been allowed to present themselves to the public as a romantic couple — a farcical staging of what they longed for but couldn't have.

Whether or not John and Paul acted on their love for one another, it seems — as we’ve talked about in prior episodes — abundantly clear they were deeply in love. Imagine what it might have been like for the two of them to perform that love as a comedy in which two men declaring their love for one another could only be seen by the audience as ridiculous.

Can you feel what it might have been like, declaring, “My love, my love, thou art my love” to the person who really is your love, and having the reaction from the audience be only mocking laughter at how daft and socially taboo that is, the notion that John and Paul might be in love. And can you feel how John and Paul might have felt, having to laugh along with the audience at the “ridiculousness” of their love?

If you’re fluent enough in the language of the Grail to be able to understand that kind of pain, then you have a sense of what performing Pyramus and Thisbe might have been like for both of them, and why maybe it’s not in actuality especially comedic or romantic. And as we talked about in the first part of this episode, maybe you have a sense of what Paul might more specifically mean, when he says his biggest regret is that he couldn't have told John he loved him — not that he didn’t or that he never had, he’s quite careful with his wording — but that the culture’s narrow definition of masculinity meant they couldn't express their love fully and honestly the way they both longed for.

If you can understand the pain of the Pyramus and Thisbe skit, you might see the deeper reason why it was significant enough in at least Paul’s life that it was still on his mind years later, when he named those kittens. And you might also see how these sorts of experiences might have been part of the inspiration for all those exuberant love songs about the joy of sharing love with the world — songs like “I Want To Hold Your Hand” and “I Feel Fine” and “I’ve Just Seen a Face” and “I Saw Her Standing There.”

If John and Paul were a romantic couple, then it’s likely that in a world in which their love wouldn't have been considered real by most of the people who bought their records, John and Paul’s songs — and especially their “mop top” love songs, so full of eagerness and the joy of new love — were the only place they could speak their love freely... there’s a place where I can go... without being ridiculed (or worse) for that love.

And you might also see that what makes their love songs more than the standard sentimental Tin Pan Alley songs of the prior generation might be that bittersweet tension, the sadness and frustration beneath the sentiment, that the joy being expressed in those songs is imagined and out of reach — because like the lovers in Pyramus and Thisbe, and outside of those precious few weeks in Paris in 1961, any public expression of that love would have been impossible.

In an indirect way, their love songs were their only way of having that love acknowledged and understood — and more importantly, celebrated by the whole world. After all, what’s more acceptable to mainstream culture — and thus more subversive — than a silly love song?

“With love's light wings did I o'erperch these walls, for stony limits cannot hold love out. And what love can do, that dares love attempt." — Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

As we’ve seen in the past few episodes, whether or not their love was physically expressed, I don’t think there’s much cause to doubt that John and Paul had — and in a very real way continue to have — an unusually close relationship. And while I certainly don’t intend this as any sort of imposition on Paul's innermost thoughts — because no one can say for certain what’s in another person’s heart — I also don’t think there’s much cause for doubt that the two of them not only loved one another, but were deeply in love, and that Paul remains deeply in love with John to this very day.

And as we started to talk about in the first part of this two-part episode, I also don’t think there’s much doubt that their love for one another was expressed in their songs.

The intimacy of their bond built a protective wall around them, enfolding them in the exclusionary circle of two that was Lennon/McCartney — John and Paul — within a circle of four that was John, Paul, George and Ringo, the four of them in turn enclosed within a fiercely loyal and protective circle of their closest friends.3

But as close as John and Paul were, like Pyramus and Thisbe, there were walls between them as well as around them, constantly shifting as their relationship unfolded and deepened.

Some of those walls were of their own making — John’s depression and Paul’s relentless work ethic, John’s insecurity and fear of abandonment, and Paul’s self-assuredness and fear of expressing love. And later, the self-imposed walls between them grew higher and thicker, with the tragic miscommunications of the breakup, followed by the separation of geography, with Paul in the UK or on tour and John stranded in America due to his immigration troubles. And after that, the thickest wall of all, when John was murdered.

But it’s likely most of the walls between them were built from the outside — by their unprecedented fame, by the respectable, subversive teen heartthrob image that Brian initially created around them that gave them the power to spark the Love Revolution, but kept them from being able to live their lives as authentically as they — and perhaps especially John — might have preferred.

And then there were the walls built between them by those who sought to drive a wedge between Lennon and McCartney in an attempt to grab some of that power for themselves, and we’ll get to all of that eventually.

And even after John’s murder, the world built further walls between them when, as we’ll talk about in a future episode, Paul struggled to even get us to believe that he and John had liked, never mind loved, one another.

And always and above all else, the wall that stood between them was built by a culture that had made love between men illegal and unacceptable, whether it was physically expressed or not, and the constant need to hide that love away from a disapproving culture — made literal in Pyramus and Thisbe by the disapproving families who kept the lovers apart.

But as the story of Pyramus and Thisbe shows us, love demands to be expressed. If it’s strong enough, it will find its way through the cracks in the wall by any means it can.

Artists, especially great artists, are driven to speak their truth in their art — to the world, to those they love, and to themselves. And for Paul and John, it seems all-but-certain that the “crack in the wall” through which they could whisper their messages to one another was their music — the one place in all of it where their mastery of craft and love of wordplay and double meaning meant they could safely express their truth, and thus their feelings for one another, without interference or censure.

The songs of Lennon and McCartney — their “whispers through the wall” — are perhaps the one line of communication that never failed them, even when everything and everyone around them — including their own demons — seemed determined to pull them apart.

In the first part of this two-part episode, we did a deep dive into “No Words,” from Paul’s 1973 album Band On The Run, to see why it’s likely what we’re calling a “JohnandPaul” song — not to be confused with a song written by both of them, but rather a song written to or about one another.

“No Words” was written in 1972, during a time when the walls between them were especially thick — at the height of their estrangement, when they were separated by both geography and heartbreak. In this episode, we’ll turn our attention to John’s “whisper through the wall” in reply to Paul’s Band On The Run, and maybe even his specific reply to “No Words” — a song called “Bless You,” from John’s 1974 album, Walls And Bridges (and btw, note the title of the album, relative to Pyramus and Thisbe).

We’re going to spend most of this episode on “Bless You,” because of its complexity and because “Bless You” — along with “(Just Like) Starting Over” — might well be John’s most important post-breakup JohnandPaul song.

We don’t yet have nearly enough context to fully talk about “(Just Like) Starting Over,” in part because by the time we get to John and Paul in 1980, the story that we think we know has so been distorted by all the parties involved — including John and Paul themselves — that it’s going to take awhile before we can untangle it. And for that matter, I’m still untangling it myself.

But if we go slowly and carefully and take our time — and if we're not afraid to say some quiet things out loud a little earlier than we probably should — I think we can find our way through just enough of the necessary context to talk about “Bless You.”

Unlike prior episodes, I’m not going to include much external research in the actual body of the text. This is a complex piece of lyrical interpretation and interrupting it for external quotes would make it too hard to follow. So the supporting research for what we talk about here will mostly be in the footnotes, along with the usual additional commentary.

After the breakup, both Paul and John, bless their tormented iconoclastic genius hearts, made launching their solo careers so much harder on themselves than it needed to be. Each of them made a series of self-sabotaging choices that — as we’ll talk about in future episodes — are entirely understandable in the context of the lovers possibility, but largely incomprehensible without it.

Paul made things harder on himself with his home-grown, cottage-core approach to Wings, putting Linda, who had no musical experience at all, in the band, and setting off on his scruffy, low-rent college bus tour, with a band that someone — I wish I could remember who — dubbed “Paul McCartney and the Semi-Professionals.” And of course, Paul’s McCartney press release widely interpreted at the time as the official announcement of the breakup of The Beatles, didn’t help, either.4 And neither did “Mary Had A Little Lamb.”5

And John, well... John made it harder on himself in let me count the ways. One of those ways was when he proclaimed that all those Lennon/McCartney songs that had changed the world were too complicated, with all those instruments and studio tricks and all those, y’know... words, and the only songs that counted for anything were simple and confessional with as few words as possible — like a haiku. And that’s why his solo work was far superior to anything he’d written when he was Fab.6

Not surprisingly, this claim was met with scepticism from nearly everyone other than John and anyone sucking up to John at the time. “The Nutopian National Anthem” was well and good for a laugh, but it was a hard sell that songs like “Oh Yoko!” and “Ya Ya” and even “Working Class Hero” and “Imagine” surpassed the profound and groundbreaking artistry of “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “A Day In The Life” and “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

Some of John’s insistence that his solo work was better than his Lennon/McCartney work was the usual Breakup John bluster and bravado — inevitable fallout from his lifelong insecurity about his talent, and an obvious attempt to cover his terror at standing solo in the sun without Paul and The Beatles buffering him from his demons.

Some of it was that. But maybe not all of it.

Writing something that’s actually simple is easy. Simple is the domain of lovestruck teenagers, amateur poets and hack songwriters. We fell in love one night in June, your eyes were shining like the moon, ooh baby baby I love you takes ten seconds to write because it’s exactly what it appears to be, which is to say not much. Listen to the Top 40 from most any era, including today, and you’ll find “moon/June baby I love you” songs all over the charts, even from some of the world’s biggest artists.

But art — and for sure, great art —is by definition more than it appears to be on the surface. It's the complexity of art — its subtext and layers of meaning — that gives great art the power to hold our attention over generations.

Complexity and layers of meaning are why we’ve spent hundreds of years studying Shakespeare and Mozart and Van Gogh — because their art is complex enough to hold our attention over not just decades, but centuries. Regardless of how often we experience great art, there is always something new to find. And complexity is why we’ll almost certainly study Lennon/McCartney for hundreds of years, too — if we can get out of our own way about their work, that is.

Perhaps the most difficult kind of song to write is a song that appears simple but maintains its complexity beneath the surface7 — which is why it’s not surprising that a songwriter of John Lennon’s calibre would be drawn to the haiku as a form. Anyone who knows anything about poetry knows a haiku is among the most challenging forms of poetry to write well, because it has to hold complexity within an extremely sparse and simple structure of just three lines and seventeen syllables.

It was a very, very narrow creative box John constructed for himself in his solo work — to write simple, confessional haiku-style songs without sacrificing the complexity required to make those songs more than just “moon/June baby I love you.”

The simpler a song is, the more difficult it is to hide subtext in it. And when we factor in the likelihood that some of those songs were written about and for Paul, the creative box John has put himself into narrows even further — to write a simple-but-complex haiku song that contains messages that your secret lover will recognise but that the rest of the world won’t notice, and to accomplish this in a form with literally no musical or poetic distractions to cover the subtext.

Think of it as trying to hide a bouquet of red roses in an all-white room with almost no furniture.

That’s an unfathomably difficult thing to do. It’s a good thing John Lennon is one of history’s most accomplished lyricists or he’d be in big trouble.

Let’s look at “Bless You.”

“A real artist, however determined he may be to hide any signs of personal intervention, however hooked on the idea of anti-art, tends to give himself away in the end.”8 — George Melly

“Bless You” was written near the end of John’s 18-month long “Lost Weekend,” during which he and Yoko were separated and John was having an affair with his assistant May Pang — an affair that was, according to May Pang, orchestrated by Yoko. And that’s a good reminder of how unusual the relationship between John and Yoko was — something to keep in mind as we continue.

The “Lost Weekend” also marked the end of John’s estrangement with Paul. In fact, when “Bless You” was written, John was considering joining Paul in New Orleans to work on Paul’s latest album. It was to have been Lennon/McCartney, together again.

May Pang tells a story about John playing “Bless You” for her and telling her that he wrote it for Yoko.9 That seems like a plausible claim. Let’s find out if it holds up.

Here’s the first verse—

Bless you wherever you are

Windswept child on a shooting star

Restless spirits depart

Still we’re deep in each other’s hearts

The opening words —”bless you,” which of course is also the title of the song — tell us right from the start that this is no ordinary pop song.

“Bless you” is a prayer in two words. It’s been spoken aloud for thousands of years to consecrate and praise, to approve and protect — and perhaps most of all, to ask for divine care for the object of the blessing. John’s use of it as both the title and the opening words signals that we’ve temporarily stepped out of ordinary space and into the sacred space of prayer. And given John's creative “strip it all down to the most honest” state of mind, he’s offering that prayer within the confines of a confessional.

By beginning with the words “Bless you,” John is telling us that whatever we’re about to hear — assuming John doesn’t subvert the blessing later in the song — can be taken as emotional truth. As a confession.10

We’ll return to the larger implications of this later. For now, let’s move on to the rest of the verse.

the obvious, surface interpretation of the next line, “wherever you are,” is to take it literally as a geographical reference. And perhaps that’s what it is — though that doesn’t tell us anything about whether the “you” in question is Yoko or Paul, because John is physically separated from both. And although he’s in communication with both of them, he probably doesn’t know for certain where either Yoko or Paul are physically located on any given day.

But it’s likely John intended something more than a literal reference to geography with that opening line. Not just because we’re presuming that since this is John Lennon, “Bless You” is more than a “moon/June” song, but also because this isn’t the first time “wherever you are” has made an appearance in one of John’s songs.

It’s also the hook in “You Are Here” from Mind Games, his album prior to the one on which “Bless You” appears11—

Love has opened up my mind

Love has blown right through

Wherever you are, you are here

Wherever you are, you are here

As a lyricist, John is often a magpie, working with found or repurposed words in the same way a visual artist might work with found or repurposed objects.

To offer just a few examples, John magpied “I Am The Walrus” from Lewis Carroll’s “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” “Cry Baby Cry” from an old English nursery rhyme and “Happiness Is A Warm Gun” from the cover of a gun magazine. He borrowed the lyrics of “Tomorrow Never Knows” from the first lines of Timothy Leary’s The Psychedelic Experience (Leary in turn borrowed them from The Tibetan Book of the Dead), and “Good Morning Good Morning” from a commercial for breakfast cereal.

“Wherever you are, you are here” is also a magpie line, slightly adjusted from the well-known aphorism in spiritual writing, “wherever you go, there you are,” which goes back at least as far as the 15th century Christian devotional The Imitation of Christ.12

The saying is meant to remind us that geography and physical distance do not in fact solve (or create) our problems, because wherever we go, we take who we are with us — our demons and fears and attachments and loves.

John did read widely throughout his life, including spiritual texts, but I doubt he spent his Lost Weekend reading 15th century Christian devotionals. So it’s more likely he picked up the line from the late ‘60s LA-based sunshine pop band The Association, whose members often quoted the aphorism as a way of talking about what it was like to tour.

John is probably using this geographical metaphor to indicate headspace as much as geographical distance — like when we say we’re mentally or emotionally in a good or a bad “place,” or when we refer to psychological distance from a situation as not being “here.”13 That kind of “wherever you are” could refer in equal measure to Yoko and to Paul (as well as to John himself). John may not know for sure where Yoko and Paul are geographically, but more relevant is that he likely doesn’t know where either of them (or himself for that matter) are in their own heads, relative to his relationship with either of them.

“Wherever you are” is especially important as the opening line of “Bless You.” Just like a foundation stone sets the frame for the structure that’s to be built on it, John uses “bless you, wherever you are” to set the frame for the rest of the song, and as we’ll see, it pairs with a later line in an important way.

For now, let’s move on to the second line, “windswept child on a shooting star.”

I’m being a bit subjective here, but when I think of Yoko Ono, “windswept child on a shooting star” isn’t the image that comes to mind. For one thing, Yoko is almost a decade older than John — even for adults, that’s a significant age gap. And in our culture and especially in 1974 in a marriage between a man and a woman, it’s unusual for the woman to be that much older.

More than that, Yoko was many things in John’s life, and while we can never know for sure what happens between a couple in private, she doesn’t appear to have been the “child” in their marriage. And she’s certainly not on any kind of fiery upwards trajectory — unless you count what being married to John Lennon did for her art career, which, okay, that’s fair. But I doubt that's what John intended with the line, and her art wasn’t exactly setting the world on fire in 1974.14

Far from being a “windswept child on a shooting star,” by 1974, Yoko seems to have been the stability in John’s life. She’s still in New York, still taking care of business — while John is off on his drug and alcohol-fueled Lost Weekend. Getting kicked out of comedy clubs and wearing Kotex on his head and living like a frat boy makes John inarguably the child at that point in their relationship.

And in fact, the line after this one — “restless spirits depart” — would seem to be John referencing himself in just this way — restless in his domestic situation with his departure from Yoko, and also restless with his departure from his creative relationship with Paul. “Restless spirits depart” also supports John’s original claim that he’s the one who left Yoko, rather than that Yoko forced John to go, as the story was later amended to and as the prevailing narrative usually insists — and we’ll get back to that in the next verse.

Still, however much “child” doesn’t seem to fit Yoko’s role in John’s life, there is precedent. John referred to Yoko as a “little girl” in “Isolation,” only two years prior. And in Japanese, the name “Yoko” translates to “ocean child” which John uses in “Julia,” a song that’s as much about Yoko as it is about his mother.15

On the other hand, “windswept child on a shooting star” is a pretty good description of Paul McCartney in 1974.16

The Oxford English Dictionary defines windswept as “exposed to strong winds.”17 And after years of exposure to the strong winds of John’s toxic breakup narrative about how Paul’s music was Englebert Humperdink and “muzak to my ears,” by 1974, that’s all — temporarily at least — fading into the past. Soaring triumphantly on the artistic and commercial triumph of Band On The Run as it dominates the charts through most of the year, Paul’s solo career is on a blazing, white-hot upward trajectory — much like a shooting star.18

If I had to make a call at this point, I’d lean ever so slightly towards Paul as the windswept child deep in John’s heart — but I definitely wouldn’t bet Paul’s farm on it. Clearly, we need more context, so let’s look at the second verse.

Some people say it's over

Now we've spread our wings

But we know better, darling

The hollow ring is only last year’s echo

If you speak American English, it’s easy to assume the first two lines of this verse are two separate thoughts — some people say it’s over, and then the next thing that happened, now that it’s over, is that we’ve spread our wings. And that might be what John intended, though it’s a bit flat-footed, like a school essay on “how I spent my summer holiday” — “first we went to Disneyland and then we visited my grandma in San Diego and then we... etc. etc.”

But the missing “that” is a British stylistic form, and despite living in New York, John seems to have retained his British speech patterns in his lyrics. it’s more likely the two lines are a single connected thought — “some people say it’s over now (that) we’ve spread our wings.” It’s a small but important detail, because it makes the link between the relationship being over and the spreading wings causal rather than merely chronological.

This couplet could for sure apply to John and Yoko. “Spread our wings” is an obvious metaphor for the freedom that comes with being single again after four years of marriage — and especially his and Yoko’s “we never leave each other’s side” marriage. And of course, “some people say it’s over” could refer to the widespread assumption that after a year and a half apart, John and Yoko have split for good.

And, of course, “some people say it’s over now (that) we’ve spread our wings” is an equally apt description of the Beatles, and specifically Lennon/McCartney, going their separate ways after the breakup, each pursuing their own creative paths in solo careers.

Obviously, though, there’s another, more specific meaning of “wings” at play here. Wings is, of course, the name of Paul’s new band — the band that’s currently soaring to the top of the charts and the heights of critical acclaim with Band On The Run.

It's beyond unlikely that John uses “wings” in a lyric without a conscious awareness of this association — just as he’ll be consciously aware of it again in “(Just Like) Starting Over.”19 And because John knows Paul as well as Paul knows John, he knows Paul is likely parsing every word of John’s songs for clues about their relationship, because Paul has told us so and there’s no reason to doubt him on this, at least in broad strokes.20

As for the first part of the line — “some people say it’s over” — obviously this tells us that the love affair in question is not, in fact, over. But there’s also a subtle hint of deception here — that “some people say it’s over” because they don’t know what’s really going on between the two lovers in the song. That “you and I” know something that “some people” don’t know.

This is usually taken to mean the press and the rest of the world that believed that John and Yoko were split for good. But it’s possible — just possible, mind you — that the “some people” in question is, in fact, Yoko.

Still, there’s nothing to tip this definitively one way or the other, relative to who John’s writing about — which brings us to the last line of the verse — “The hollow ring is only last year's echo.”

I cautioned earlier that to understand “Bless You,” we’d have to be willing to say some quiet things before we’re really ready to. Most of those quiet things are hiding in this line.

As always, let’s look first at the literal.

In a love song, a ring virtually always means a wedding ring. The imagery of a hollow ring suggests a wedding ring that’s not on a finger — the hollow part being the empty centre of the ring when it’s not being worn. A wedding ring not on a finger implies a broken engagement or a broken wedding vow, the latter of which would seem to point to the breakdown of John’s marriage to Yoko. Not exactly a stunning revelation, given they’re currently separated, John’s living with May Pang and Yoko’s reportedly having an affair of her own.

But lyrics need to be taken in context. The full line is “the hollow ring is only last year’s echo.” An echo is, of course, the lingering trace of something that’s already happened. So the broken vow is in the past. Maybe this is John telling Yoko that their marital troubles are just a memory, and that John is hopeful that he and Yoko can repair their marriage.

All of this is more or less consistent with the story as it’s currently told. But there’s another meaning of “hollow ring” that suggests another possible interpretation of the line — given that when John writes “Bless You,” he’s still over half a year away from reconciling with Yoko, but is at the time currently in the process of reconciling with Paul.

You might recognise the phrase “hollow ring” as an expression that means something put forth as if sincere but that doesn’t feel sincere. It’s similar to the expression “empty promise.” And paired with the wedding ring association and the context of the song, this meaning of “hollow ring” suggests an empty wedding vow that “rings hollow.”

“The hollow ring is only last year's echo” could mean that for John, it’s not the separation, but the vows themselves that were hollow — that “JohnandYoko” was never the epic romance he insisted it was at the time, and that he’s ready to acknowledge that — at least to the one person he might be writing the song for, the only other person in his life who works at the same level of lyrical sophistication as John does and who would therefore get the reference.

This is one of the quiet things, and we’re getting ahead of ourselves here, but though this might feel like a reach, I don’t think it is — especially given the tortured, tangled, heroin-addled Paul-just-married-Linda-so-now-I-have-to-marry-Yoko-right-away circumstances under which John and Yoko’s vows were exchanged, and John’s overall tendency to act on impulse.

And more than that, I don’t think it comes as a big revelation that there was an obvious element of performance in the JohnandYoko relationship — particularly in those first years. Yoko is, after all, a first and foremost a performance artist whose primary interest has always been in challenging mainstream cultural norms, including the cultural norms surrounding love, sex and marriage. Yoko and John as a couple did quite a bit of challenging those cultural norms. And John has explicitly said that their wedding and honeymoon, as well as — in a certain way at least — their marriage, was an act of performance art.21

Consider the extreme over-the-topness of never leaving each other’s side, the naked Two Virgins album cover, the dramatic and theatrical wedding in Gibraltar that became “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” the public bed-in-for-peace honeymoon, John playing the sex tape of him and Yoko at the Beatles meeting, the bed brought into the studio during the Abbey Road sessions, complete with Yoko in a literal tiara, and on and on and on and on.

In our “document everything on social media” culture, it’s easy to lose sight of the reality that none of this is by any standard at all a healthy or normal way to live a relationship — not even in the dying light of the countercultural Love Revolution. This is theatre — a love affair and a marriage not lived, but performed as a statement about love and marriage.

Even some of the songs that John wrote about his relationship with Yoko — I’m thinking in particular of “Oh Yoko!” and later in 1980, “Dear Yoko” — are so over-the-top in their exaggerated expressions of extreme (albeit joyless) devotion that it’s hard not to conclude they’re intended more as satire than as sincere expressions of marital bliss.22

But even here, I wonder if the JohnandYoko show was really intended as a political statement at all — at least on John’s part.

We’re again getting way too far ahead of ourselves in saying some quiet things, but it’s hard not to wonder if John performing of the “great romance” of JohnandYoko was in large part a passive-aggressive swipe at Paul — because John publicly performing perfect marital bliss for a lover he’s still in love with who’s married someone else is very much something a man with poor impulse control and major trust and abandonment issues who’s also prone to jealousy and possessiveness might do, under the guise of making a political statement with a performance artist.

But now we really are getting so far ahead of ourselves we might need a GPS to get back. So let's just say there's an old saying — “marry in haste, repent at leisure.” And by 1974, well into the Lost Weekend, John might be doing a bit of repenting of the performance art circus of JohnandYoko.23

If “the hollow ring is only last year’s echo” is John's acknowledgement of the performative nature of his marriage to Yoko, then the “darling” in “but we know better, darling” isn’t Yoko, it’s Paul.

And if “Bless You” is written for Paul, then the “hollow ring” line is John’s reassurance — not to Yoko, but to Paul — that everything that’s happened over the past years between them — the pain, the anger, the separation of the breakup and his performative marriage to Yoko — is now in the past, because John is starting to realise the damage he did during the breakup, in the same way that any recovering addict begins to see the damage they did, when their head finally clears.24

I’m not in any way claiming that any of this for sure means that the “hollow ring” line means John and Yoko’s marriage overall was only an act of performance art, or that “Bless You” is John confessing this to Paul, or even that “Bless You” is written for Paul — how could I possibly know any of that for sure? The point is that the line — and the song thus far — is ambiguous. It fits John’s relationship with Paul as much — and sometimes better — than it does his relationship with Yoko.

What I’m proposing is that there might be a second, “shadow song” beneath the surface of “Bless You,” precisely overlapping the more “public” song, with every line having two meanings — the surface meaning shaded towards Yoko and the less obvious meaning shaded towards — and nearly invisible to anyone but — Paul.

While others have picked up on the idea that John’s songs are often about more than one person, and that two lines can refer to two different things at the same time, what I'm talking about here is slightly more sophisticated and more Lennon-esque than a simple double meaning—

That “Bless You” contains a surface song and a shadow song. The surface and relatively straightforward song is intended to distract us with what we expect to hear — a song about Yoko. And beneath it, a far more sophisticated shadow song — sophisticated enough that a fellow genius with an intimate, shared history, would recognise in a way others wouldn't.

I’m suggesting that in writing “Bless You” — as well as other songs in his solo work — John may be using the same techniques as a stage magician does — misdirecting us with one hand while performing the actual illusion with the other hand.

And now’s a good time to remind you again that this is John Lennon we’re dealing with — who is known in his work for his use of double meanings, subtext and sophisticated and difficult-to-interpret wordplay, and who enjoys tricking people with his words.

Let's look at the third and final verse—

Bless you whoever you are

Holding her now

Be warm and kind hearted

Remember though love is strange

Now and forever our love will remain

If something about this verse is throwing you, it’s probably the sudden appearance of “her.” Because whether “Bless You” is written to Yoko or to Paul, it’s written in the second person — meaning it’s written to the “you” of “wherever you are” in the first verse.

So who is this new character, the “her” who has appeared out of nowhere in the final verse? And for that matter, who’s the “you” in “whoever you are,” also in the final verse? Because up until now, the “you” in the song has been John’s beloved, be that Yoko or Paul.

The conventional answer is that the “her” in “holding her now” is Yoko, and thus the “whoever you are” is Yoko’s Lost Weekend lover — which, okay, story-wise, that’s plausible, so let’s go with that. For now, let’s assume “Bless You” is written for Yoko, and that in the final verse, John has shifted the meaning of “you” and is now talking not directly to Yoko, but to whoever is holding Yoko in their arms in John’s absence, aka Yoko’s lover.

And if that’s the case, that means that John is asking Yoko’s lover to be “warm and kind hearted” to her. Which, okay, that’s nice. Is this like when George Harrison gave Eric Clapton his blessing to marry Pattie because if she was going to leave George, then he’d rather she was with someone he could trust? Maybe, but doubtful, given “whoever you are” suggests John doesn’t seem to even know Yoko’s lover’s name.

But if that’s the case — if “whoever you are” is Yoko’s lover — then that also means that John has shifted the meaning of “you” from Yoko to Yoko’s lover, and he’s now addressing the lyric to Yoko’s lover rather than to Yoko. Which is fine on its own — sort of — but if that’s the case, who is the “our” in the final line, “now and forever, our love will remain”? Who is John talking to, when he says that?

Convention would say that “our love” refers to John and Yoko’s love. So let’s see if we can make that work.

Maybe John’s warning Yoko’s lover that he (or she) can have their fun, but ultimately, Yoko is John’s. John did have abandonment and thus jealousy issues, and he did write about his jealousy. But “Bless You” doesn’t seem even remotely like a jealousy song. It’s not “Run For Your Life” or “You Can’t Do That” or even “Jealous Guy.”

“Bless You” also doesn’t even remotely seem like a competitive “keep your hands off my baby” song of rivalry with another man for Yoko. And it also doesn’t seem like a “have your fun, but her love with me is stronger than what you have with her” song —especially since the lover doesn’t even enter the picture until the final verse (if at all).

So what exactly is John’s plan here? Is he in fact subverting the sacred confessional that he’s established at the beginning of the song? Is he asking Yoko’s lover to pass along John’s intimate affirmation of his and Yoko’s love — “now and forever our love will remain”— to Yoko on his behalf? Like, Yoko’s lover is a messenger or something?

This too seems unlikely. Because what “Bless You” does seem to be is an intimate, vulnerable reassurance, spoken directly to a lover, that even through adversity and separation, “our love will remain.” And that intimacy has been building up to those last two lines — the climax of the song — the reaffirmation that John and his beloved’s love endures despite geographical and emotional separation.

Remember, John is in both haiku and confessional mode — and that means he’s writing simply and straightforwardly about his feelings. So why, after all of that confessional intimacy, would John make the most important part of his message indirect? And to someone he doesn’t even know? John doesn’t need a go-between in the final lines to affirm their love. He’s been doing just fine speaking directly to his beloved in the first two verses.

All of which is to say that the “our” of “our love will remain” is clearly John and his beloved, the person he’s writing the song to. But if the “her” in the song is Yoko, then that final message of the song — “our love will remain” — doesn’t seem to work, at least not if the “our” is John and Yoko.

What I’m saying is that if the “her” in the song is Yoko, “Bless You” doesn’t just fall apart thematically. It also falls apart grammatically. And this is John Lennon, who bends the English language to his will. He understands better than most people what words mean and how grammar works. And grammar needs to work the same regardless of who’s writing a song — that’s what keeps a song from turning into incomprehensible word salad.

For example, take “I Am the Walrus.” As absurdist as "I am he as you are he, as you are me and we are all together” is, it works as absurdism only because those pronouns mean what we know they mean, and they work in the line the way we all agree that pronouns work.

John is playing with our perception of identity in “I Am the Walrus,” but he’s not breaking grammatical rules by making words mean something different than we’ve all agreed that they mean. If John was changing what words mean and how the English language works, we wouldn't have any way of understanding the line at all, and it would deteriorate into nonsense. Not absurdism, which is what “I Am the Walrus” is, but actual meaningless, incomprehensible nonsense.

John isn’t writing nonsense in “Bless You.” He’s not even writing absurdism. “Bless You” is a confession and a prayer. The message needs to get through clearly and unambiguously.

I know this is subtle and a little complicated. It twisted my brain, too, and still does — and that is on-the-mark for a John Lennon lyric. So let’s step through the final lines of “Bless You” using the basics of English and musical grammar — which, again, remain the same even if John’s playing with the form.

Here’s the last verse again —

Bless you whoever you are

Holding her now

Be warm and kind hearted

Remember though love is strange

Now and forever our love will remain

If the “her” in the final verse is Yoko, and the “whoever you are” is Yoko’s extramarital lover, and “our love” is John and Yoko, that would mean that after the first two verses in which John is talking directly and intimately to Yoko, he switches — with no lyrical or musical cues to signal the shift — to talking to a nameless lover about Yoko. Which, because it happens at the beginning of a new verse, is scruffy but still barely workable.

But then, for the final two lines — in the middle of both a thought and a verse, and again with no cues to signal the shift — he switches back to talking directly to Yoko about “our love.” And if you're confused yet, well... yeah.

To put it another way, according to the basic rules of grammar, for “Bless You” to be about Yoko, the “you” would have to shift its meaning from referring to Yoko in the first two verses to referring to Yoko’s lover in the first four lines of the last verse, then shift its meaning again for the final two lines of the last verse back to referring to Yoko — all of it with no lyrical or musical cues to signal those changes.

It would be like if I was talking to you and then in the middle of the sentence I started to talk to someone else about you — without any signals to you that I’d switched gears — and then later in the sentence, I switched back to talking directly to you — without any signals to you that I’d switched gears again.

And if that’s really what’s happening here, that’s not subversion of the form or John Lennon playing with words. It's just jaw-droppingly bad writing — and by “bad writing,” I don’t mean “not as good as ‘Strawberry Fields Forever.’” I mean actual incompetence in which the writer literally does not have even a basic grasp of how either musical structure or sentences or pronouns work.

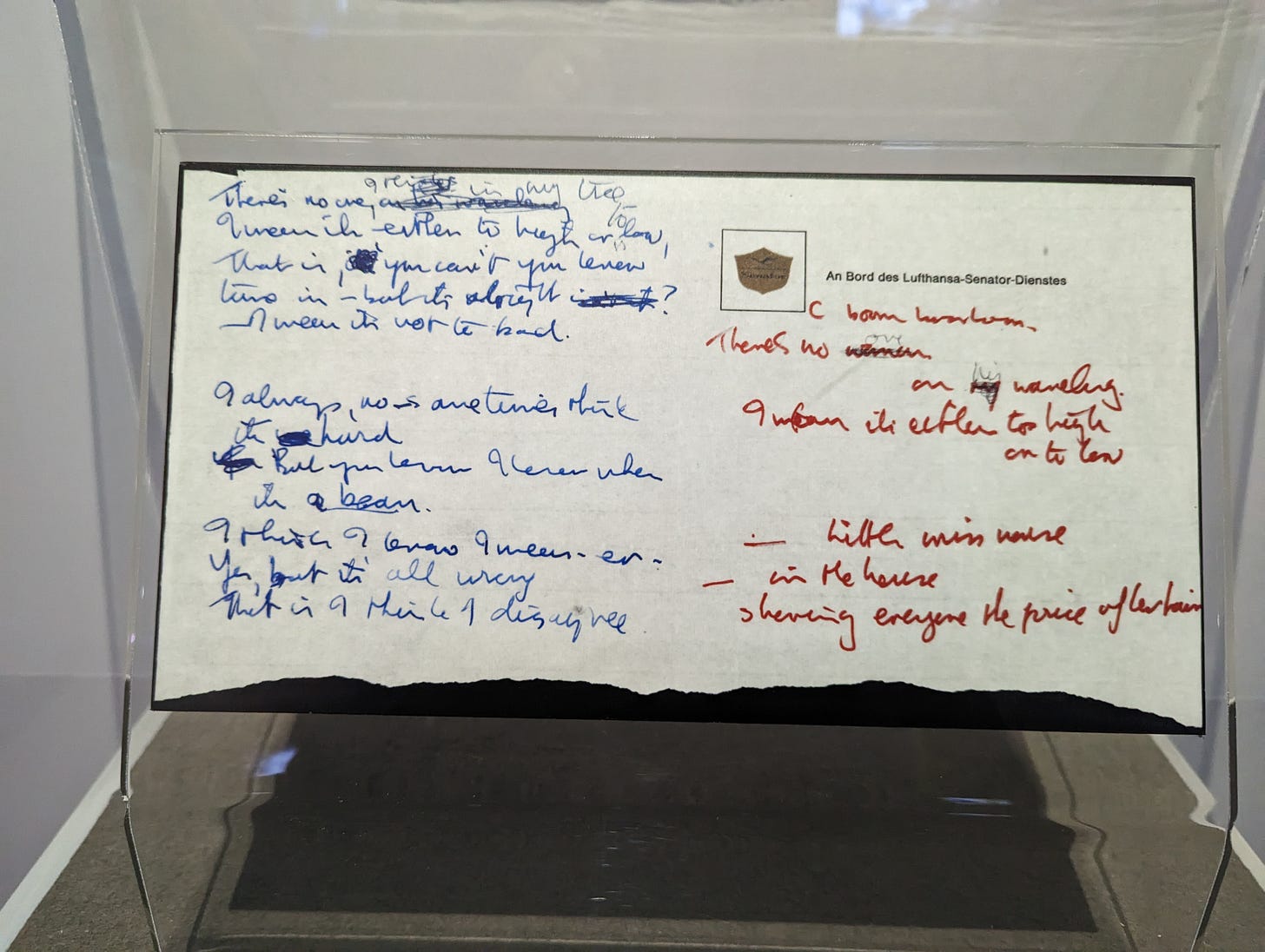

Even in his Lost Weekend drug-fueled haze, even if he’s writing a substandard lyric, John Lennon knows how sentences and pronouns work, and he certainly knows how musical cues in songs work. By the time he writes “Bless You,” he’s been a professional writer at the very top of his craft for a decade. He’s one of the most accomplished and sophisticated lyricists in music history— the writer of “I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together,” and “Always, no — sometimes think it's me/But you know I know when it's a dream”25 — complex observations on the dissolution of the ego that incontrovertibly require mastery of pronouns and grammar, or those lines wouldn't be what they are.

And if there is truth to the lovers possibility, John would be especially aware of the use of pronouns in a song, given that many of his and Paul’s songs to and about one another would have — out of necessity — altered the grammatical pronouns to conceal their love affair.

The point of all of this madness is that if “Bless You” is about Yoko, then the “her” really can’t be anyone but Yoko, or the song collapses in on itself. And if “Bless You” is about Yoko and the “her” is Yoko, then the song also collapses in on itself, both thematically and grammatically.

To make sense of “Bless You,” we may need to resort to drastic measures. We may need to take John at his word when he says he’s decided only simple, confessional songs are worth writing.

What if John hasn’t done anything complicated here at all? What if the final verse of “Bless You” is saying exactly literally what it says, with no grammatical monkey business? And what if what it says isn’t what we’ve always assumed it says?

John’s also the co-writer of “If I Fell,” another likely JohnandPaul song, though we won’t go into detail about it here. What’s important here is that like “Bless You,” “If I Fell” is also a simple, confessional declaration of love. And more than that, the pronouns in “If I Fell” are used virtually identically to the way they’re used in “Bless You.”

Here’s a verse from “If I Fell.” Notice the use of the pronouns — “you, “her,” and “our.”

If I trust in you, oh please

Don't run and hide

If I love you too, oh please

Don't hurt my pride like her

'Cause I couldn't stand the pain

And I would be sad

If our new love was in vain

Artists tend to use similar patterns across multiple works. All three pronouns in this verse of “If I Fell” — “you,” her” and “our” — are used the same way and in the same order as in the final verse of “Bless You.” And we all understand with no trouble at all that the “her” in “If I Fell” is not the same person as the “you” that the songwriter is falling in love with, and that the “you” is also the “our” of “our new love.” There is no confusion or ambiguity here at all.

So why can we see this so easily in “If I Fell,” but not in “Bless You”?

The answer is, because in “Bless You,” we’re making the assumption up front that the song is about Yoko, because that’s what we expect in a love song written by John after 1968. And more than that, we’ve been conditioned by the culture to assume a love song written and sung by a man is about a woman. And so confirmation bias bends our experience to fit those expectations — even when the actual lyric self-evidently doesn’t line up with that assumption.

This happens a lot when it comes to John and Paul’s songs, both together and solo. To bend the lyrics to our culturally-conditioned expectations, we ignore inconsistencies and rearrange our experience of the song to fit what we think is there, instead of hearing what’s really there.

What I'm saying with all of this is that “Bless You’ can either be about Yoko or it can make sense, but not both. And the only other person it could reasonably be about, given everything else in the song, and given what we know about John and about this time period, is Paul.

But wait, what about the story May Pang tells of John playing “Bless You” for her and telling her it’s about Yoko?

Well, let’s be careful not to make the same mistake on the opposite side, by thinking that if “Bless You” is for Paul, it can’t also be for Yoko. Maybe it’s for both of them.

John works with layers of meaning. Maybe he wasn’t fibbing when he told May “Bless You” was for Yoko. Maybe he just left out the part about how it’s also — or even mostly — for Paul. Yoko isn’t a lyrical genius — and that’s not meant as a putdown, most people aren’t lyrical geniuses — she’d be fine with the surface song, even if it doesn’t actually make sense on closer inspection.

Either way, May Pang has confirmation bias of her own. She’d assume that “Bless You” was for Yoko, whether John told her so or not, and John would know that. And since Yoko put her up to the whole “having an affair with John” thing in the first place, and since May Pang was working as Yoko’s assistant while John was recording Walls and Bridges, John might be especially motivated to let May think “Bless You” is about Yoko.

And knowing that people will see what they expect to see would be why John can get away with putting “Bless You” on the album in the first place without making it obvious that he’s written the deeper shadow song for Paul. John’s counting on everyone — other than Paul — hearing what we expect to hear and assuming it’s for Yoko — and only for Yoko — so as to conceal the deeper meaning of the song in plain sight.

In short, John seems to be hiding a bouquet of red roses in a white room.

If you’re still thinking this sounds like a reach, remember again that this is John Lennon, and as we all know, John is a writer who loves more than anything to play with the meaning of language so as to deceive, inveigle and obfuscate. And also as we all know, he’s a lyrical genius who does that specific thing better than virtually anyone else ever has. None of that goes away just because he’s set a new goal of writing within a simple, confessional form.

And that in and of itself is support for the credibility of the lovers possibility — because what makes more sense? That John Lennon would write a lyric that’s a nonsensical mess, or that John Lennon would write a song that brilliantly seems to have one meaning, but has another entirely different meaning superimposed underneath?

Before we take an even closer look at the final couplet of “Bless You,” there’s a bit more to say about “whoever you are” — which also points us towards the song being for Paul and not Yoko.

“Whoever you are” calls us back to the opening lines, “wherever you are, windswept child on a shooting star,” which we talked about could be a description of Paul caught up in the runaway success of Band On The Run.

Just as John no longer knows for sure where Paul is on any given day, geographically or emotionally, John also maybe no longer knows for sure “who” Paul is. Yes, they’ve to some extent reconciled during the Lost Weekend, but Paul’s life has changed so much since the breakup — a new wife, a new family, a new band, and apparently a whole new wardrobe.

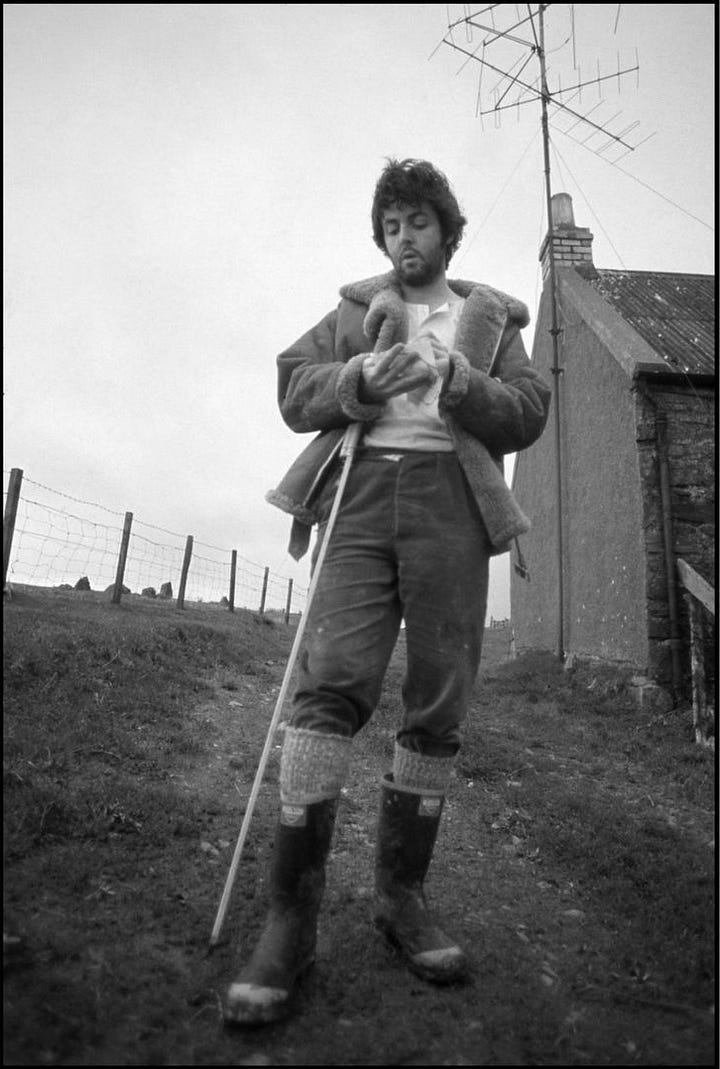

The change in Paul after the breakup is hard to wrap my head around even today. Paul McCartney, the glamorous bachelor prince of Swinging London, leading member of the avant garde counterculture, who dazzled at art openings and theatre premiers became — almost overnight — traditional husband and father-of-two Farmer Paul living on a remote Scottish farm populated by actual literal sheep.

As we’ll see when we get there in the story, that change was probably the sanest thing Paul could have done — and that change, along with Linda, probably saved his life. But it was nonetheless spectacularly disorienting to the rest of the world, including almost certainly John. And it wouldn’t be at all surprising if John was worried that Paul had changed so much that maybe their bond couldn't be rekindled. Maybe that’s the meaning of “whoever you are.”

We’re not quite done with “Bless You” yet. Because there’s still those final two lines —

Remember although love is strange

Now and forever our love will remain

John will write “now and forever” again and more famously in 1980 in “Woman,” and again, we don’t have context yet to talk about that. For now, it’s the first line of the couplet that I want to call our attention to.26

You might assume when John says “love is strange,” he’s generically musing on the unpredictability of love.

Or maybe we’re back to Yoko again, however implausibly — because if there was a stranger high-profile couple in the ‘60s and even the ‘70s than John and Yoko, I’m hard-pressed to think of who it would be. John and Yoko were so strange, in fact, that Richard Neville, the editor of the ‘60s countercultural magazine Oz, who was apparently acquainted with every high-profile freak in England, listed John and Yoko first in his informal rundown of Fabulous Freaks in his 1995 memoir of the Sixties, Hippie Hippie Shake.27

But there’s something more interesting going on with these last two lines than the performative strangeness of JohnandYoko.

Because in “Remember although love is strange,” both the “remember” and the “although” imply that John is referencing something that's been said and shared previously between the two lovers.

We’ve talked about John’s tendency to magpie — to repurpose found material in his songs. And not surprisingly, what he mostly magpies is other songs.28

We’ll talk about the very first ever Lennon/McCartney magpie in the next Rabbit Hole. And another early instance is “There’s A Place,” the title line of which John (and Paul) borrowed from the song “Somewhere” from West Side Story — which is, by the way, a song sung by two lovers separated by a disapproving culture. In “If I Fell,” John (and Paul) obliquely reference “I Want To Hold Your Hand.” Then in “Run for Your Life,” John magpies the title from the Elvis song, “Baby, Let’s Play House.” John quotes “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds” in “I Am The Walrus,” and he quotes “Fool On The Hill,” “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Lady Madonna” in “Glass Onion,” and Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man” in “Yer Blues.” Most notoriously, John magpies the opening line of “Come Together” (along with a good bit of the melody) from the Chuck Berry song, “You Can’t Catch Me.”

The lyrical magpies continue with John’s solo work. We won't go through all of them, but on “Mother,” John borrows “children don’t do what I have done” from the folk song “House of The Rising Sun.” And he magpies the signature lyrical hook from Sam Cooke’s “Bring It On Home To Me” on “Remember” (which may also be written to Paul, who was in self-imposed exile in Scotland at the time).

John also magpies on Walls And Bridges, the album that “Bless You” is on. There’s a call back to Little Richard’s “Rip It Up” on “What You Got?”, when John sings “Saturday night and I just got paid.” “Old Dirt Road” includes lyrical references to Curtis Mayfield’s “Keep On Keeping On” and Marty Robbins’ “Cool Clear Water.” And “I’m Scared” calls back to Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” (although that one might not count since by 1973, “like a rolling stone” had entered the language as an expression independently of Dylan’s song).29

You might have noticed the magpie moment in the final verse of “Bless You.”

“Love Is Strange” was written by Bo Diddley and covered by, among others, skiffle star Lonnie Donegan, Mickey & Sylvia, Buddy Holly and the Everly Brothers. But unless you’re familiar with the lesser-known 1971 Wings album, Wild Life, you might not know that Paul also recorded “Love Is Strange.”

Paul’s recording of “Love Is Strange” is in of itself a bit strange. Paul didn’t just record a straight-ahead cover. As he and John often do, he reworked the lyrics — which is why it’s never a good idea to discount cover songs when it comes to John and Paul, and especially relative to the lovers possibility, and we’ll talk more about that in the next Rabbit Hole.

We won’t go deep into Paul’s rework of the lyrics of “Love Is Strange,” but it’s worth noticing just a couple of changes he makes to the original—

First, he changes the opening line, “love, love is strange,” to “baby, love is strange,” and later in the song, to “my sweet baby, love is strange.” This seems like a trivial tweak, but it’s not. It shifts the point of view of the song from an abstract third person musing on love in general to a song sung directly to a specific person — his “sweet baby.” Unlike previous versions, Paul isn’t just talking about love being generically strange, he’s talking to his lover about their love being strange.

Paul and Linda were strange as a couple only in that they were so disconcertingly normal. But if John and Paul were indeed lovers, then as strange as John and Yoko were as a couple, Paul knows that John and Paul as a couple are strange, too — or at least they were in 1974, when a man in love with another man was still considered aberrant by a majority of Brits and Americans. And of course Paul’s also going to be aware that their lives as Beatles overall are strange compared to most people’s, and have been from the time they were both teenagers.

The second significant adjustment Paul makes to the original lyrics of “Love Is Strange” is that he omits the couplet that refers to love as a “fix” he can’t get enough of.

Fix is a term specifically associated with heroin use. And Paul’s omission of that reference in “Love Is Strange” is probably in part his general reluctance to include hard drug references in his songs. He and the other Fabs did after all veto “Cold Turkey,” John’s heroin addiction song, as being inappropriate subject matter for a Beatles album.

But it might be more specific than that.

Paul frequently emphasises in Many Years From Now how concerned and troubled he was by John’s heroin use. The omission of the “love is like a fix” verse might also be motivated by a desire to avoid equating his love for John with John’s heroin habit.30

And finally, Paul changes “a lot of people take it for a game” to “many many people take it for a game.” And it’s at least possible that he’s referencing John and Yoko here, in their performative public love affair — because Paul records “Love Is Strange” only been a few months after the release of “Too Many People,” in which Paul has explicitly told us that the “too many people” of the title refers to John and Yoko.31

Of course, none of Paul’s lyrical changes prove that “Love Is Strange” was recorded as a “whisper through the wall” to John, although they certainly point in that direction. And it’s one more addition to that accumulating body of supporting research that we’ve talked about.

And “Love Is Strange” also reminds us of the need to avoid looking at individual data points in isolation and to look at them in context — because John’s referencing of “Love Is Strange” in the final verse of “Bless You” is yet another clue that “Bless You” is written for Paul.

Just as Paul’s “tell” that he’s writing to and about John seems to involve regret at having not expressed love, one of John’s “tells” that he’s writing to and about Paul seems to be his use of either Lennon/McCartney or Paul’s solo song titles and quotations in John’s own songs.

We’ve already noticed several of these tells — the callback to “I Want To Hold Your Hand” in “If I Fell” — both possible JohnandPaul songs, the possibly ironic “Oh Yoko!” when John quotes “I Call Your Name,” possibly as an aside to Paul. And in “Glass Onion,” which we know was at least partly about Paul because John mentions him by name. And in the next Rabbit Hole, we’ll talk more about “I Know (I Know)” on Mind Games, which contains the line “getting better all the time.”32

John’s most notorious magpieing of “Paul songs” is, of course, in “How Do You Sleep?” — obviously a song about Paul, at least consciously at the time it was written33 — when he rhymes “Yesterday” with “Another Day” — both Paul songs. And “Another Day” in turn makes another appearance on “What You Got?” on Walls And Bridges, another possible Paul song, and yet again — along with a reference to Paul’s song, “My Love” — on “(Just Like) Starting Over”, which is also likely written to Paul, although we’ll need a lot more context to talk about that one.

And of course, “Bless You” includes a magpie of “Love Is Strange.”

If “Bless You” is indeed written to Paul — as it appears to be — it’s a beautiful and haunting exchange of whispers through the wall.

Paul whispers to John with his cover of “Love Is Strange” that, well, that their love is strange, and also that it’s serious, and not the game that the two of them have maybe been playing during the breakup — and/or maybe the game John and Yoko have been playing by performing their marriage as theatre.

John whispers back with the final two lines of “Bless You” — “Remember although love is strange, now and forever our love will remain” — John's message of reassurance and reconciliation, not to Yoko, but — for the rest of the song to make sense — to Paul.

“Bless You” is where we get to choose whether we believe John Lennon is John Lennon, one of history’s most accomplished lyricists, or just some other guy who writes average songs and doesn’t understand how the English language works.

And if John Lennon is the same John Lennon who wrote “Strawberry Fields Forever,” then “Bless You’ is an intricately crafted “shadow song” — with the actual meaning of the song occupying exactly the same footprint as the surface song. And in which the surface song seems to say what the world expects it to say, and the shadow song beneath the surface contains a message intended exclusively for a very special audience of one — the only other songwriter in the world who would understand that message, because he, too, is a master wordsmith, and because he's spent over a decade writing in “entangled form”34 with John.

We’re not quite done yet, though. John has one final lyrical trick up his sleeve, and it’s maybe my favourite thing about “Bless You.”

The first verse of “Bless You” starts with “wherever you are,” and the final verse starts with “whoever you are.” Together, they’re what (for lack of time to research poetry terms) I’m going to call a split couplet — two lines that obviously belong together but are physically separated in the lyric.35

Using a split couplet as a framing device on its own isn’t unique or all that sophisticated. “Split couplets” — or whatever they’re called — are often used at the beginning and end of a lyric as a framing device for the song as a whole. And that’s what “wherever you are/whoever you are" is doing in “Bless You.”

What’s unique and sophisticated is how John uses this particular split couplet. Because instead of subverting the theme of the song as a blessing, he's using the lyrical structure of “Bless You” to reinforce that theme.

This is, once again, a little hard to explain, but stay with me here.

The split couplet — “wherever you are” and “whoever you are” — consists of two lines meant to be together but physically separated, just like the lovers in the song. And further, the language of the split couplet itself — “wherever you are” and “whoever you are” — references both geographical distance and emotional separation — which are the two thickest walls between John and Paul at this point in their relationship (other than cultural disapproval, of course).

What joins the split couplet back together in the lyric is the “hollow ring” middle verse, in which John confesses his remorse for having caused pain and reaffirms the constancy of their love — which is also in real life what’s required for the lovers to reconnect with one another across emotional and geographical estrangement.

By using a split couplet to join the opening verse to the closing verse, John uses the structure of the song to re-create the lyrical theme of separated lovers re-united by their love. The structure of the song echoes the current real life structure of the relationship that the song is about.

This, combined with the shadow song, is stratospherically advanced songwriting that only a handful of songwriters could pull off. And there is no doubt whatsoever that John Lennon is one of those songwriters.

Musically, “Bless You” is obviously missing the McCartney touch (and also the George, Ringo and George Martin touch). But lyrically, it might be one of John’s finest moments as a songwriter. And here's the thing — the lyrical mastery in “Bless You” is only visible when we allow for the possibility that he and Paul were a romantic couple.

This is another example of how the lovers possibility adds complexity and depth to their music that’s not visible otherwise.

When we let go of our expectation that the song is about Yoko and allow for the possibility that it's about Paul, the apparent average-ness of “Bless You” resolves itself, and the song becomes an elegant, intimate confession of love in the face of adversity and separation — consistent with John’s extraordinary and intuitive skill as a lyricist.

Before we move on from “Bless You,” you might have noticed we haven't yet sussed out the identity of the mysterious “her” in the final verse — though perhaps it’s now self-evident who the most likely candidate would be. If the “her” isn’t Yoko, then it’s also not Paul for the same reason it’s not Yoko. And it’s not May Pang, for many reasons — including that when he writes this song, John is the one holding May Pang.

To understand the likely identity of “her” in the final verse means we once again have to get ahead of ourselves and say some things before we’re quite ready to say them.

If “Bless You” is written for Paul, then the “her” in the final verse can only be Linda, as John urges Paul to”be warm and kind hearted” to the woman who’s become Paul’s culturally-approved, public romantic partner in a way that was denied to John, given the prejudice of the times. And that means that —again, if “Bless You” is written for Paul — John is sending this message of goodwill to the woman he’s been jealous of since she first appeared in Paul’s life.

John’s jealousy of Linda is well-documented, though Grail-phobia and fear of softness keeps most writers from calling it what it self-evidently is.36

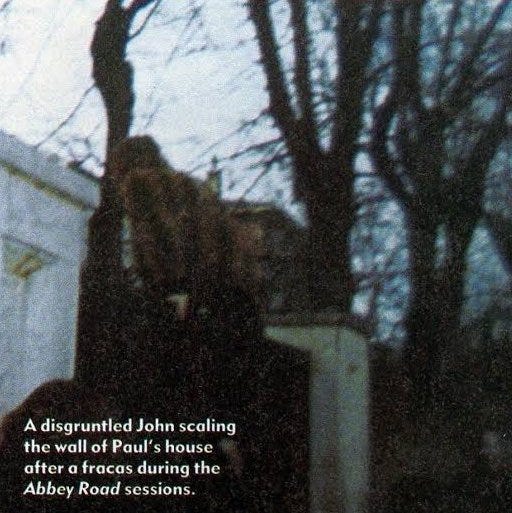

During the recording of Abbey Road, John climbed over the wall of Paul’s London townhouse to get to Paul, because Paul had skipped a studio session to have an anniversary dinner with Linda. (And, btw, we know this happened because the Apple Scruffs waiting outside Paul’s gate photographed John climbing the wall.)

And it mostly goes unremarked on that after living with Yoko without being married for almost three years — and despite John and Yoko’s stated opposition to the concept of marriage — the day Paul and Linda were married, John declared a wedding emergency. He tried to get a ferry captain to marry them. And when that didn’t work, he chartered a plane to Paris for him and Yoko. And when that didn’t work, he demanded that Apple employee Peter Brown find somewhere that John and Yoko could get married with no delays — which is why they were married in Gibraltar, only eight days after Paul married Linda.37

In two separate letters to Paul during the breakup, John wrote that he gave Paul’s marriage to Linda two years before Paul left Linda and came back to John.38 And in an announcement of Paul and Linda’s wedding in a 1971 Beatles promotional booklet, John crossed out “marriage” and wrote “funeral.”39

To anyone even a little fluent in the language of the Grail, these are obvious and classic signs of jealousy. But perhaps the most telling of all is a 1971 interview in which John reveals — though probably unintentionally — the specific contours of his jealousy of Linda.

John was asked n the interview when he first met Linda and if he got along with her. He answers with the following —

"The first time was after that Apple press conference in America. We were going back to the airport and she was in the car with us. I didn't think she was particularly attractive. A bit too tweedy, you know. But she sat in the car and took photographs and that was it. And the next minute she's married him."

Even more telling, in the same interview, John is then asked about Paul’s marriage to Linda. After a lengthy rant about how — to John’s frustration — teenage Paul was frequently reluctant to disobey his father, John concludes his apparent nonsequitur with—

“I was always saying, 'Face up to your dad, tell him to fuck off. He can't hit you.You can kill him (laughs) he's an old man.' I used to say, 'Don't take that shit.' But Paul would always give in to his dad. His dad told him to get a job, he dropped the group and started working on the fucking lorries, saying, 'I need a steady career.' We couldn't believe it. Once he rang up and said he'd got this job and couldn't come to the group. So I told him on the phone, 'Either come or you're out.' So he had to make a decision between me and his dad then, and in the end he chose me. But it was a long trip."40

The reason we’re talking about this interview — and this is not my original observation, but the work of an excellent scholar and writer in the Beatles studies counterculture — is that John’s answer to what Paul wants in a woman is to tell the story of how Paul chose John over his father when he quit his management trainee job and returned to the band in February 1961.41