All the episodes of Beautiful Possibility in sequence are here.

This episode works on its own without having listened/read anything else.

“Fans or readers, or even critics, who really want to learn more about my life should read my lyrics, which might reveal more than any single book about The Beatles could do.”1 — Paul McCartney

The legend of the Grail is probably the most important mythological story woven into the larger mythological story of The Beatles, but it isn’t the only one.

Pyramus and Thisbe are two lovers kept apart by families who don’t approve of their affair. They live in adjoining homes, separated by a plaster wall, and their only way to communicate is through a crack in that wall. One night, unable to bear being apart a moment longer, they plan a secret meeting in the nearby woods, where a tragic misunderstanding results in their mutual deaths.

The myth of Pyramus and Thisbe first appeared in Western literature in 8 A.D. in the Latin poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses, but it almost certainly dates back much further. And while it’s not as mythologically influential as the legend of the Grail or story of The Beatles, the influence of Pyramus and Thisbe is significant. For one thing, it was the source material for Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Western culture’s most iconic story of love denied by cultural disapproval.2 And of course, Romeo and Juliet inspired, among countless other works, the musical West Side Story — reportedly the only musical John liked, and the film version of which he and Paul went to see together in February of 1962.3

Two years later, in April 1964 at the height of Beatlemania, The Beatles performed a traditional British pantomime skit of Shakespeare’s version of ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ from Midsummer Night’s Dream as part of their BBC television special, Around the Beatles. Paul played the role of Pyramus, and John, in the custom of Shakespeare in which men traditionally played the female roles, played Thisbe.4

Oscar Wilde once said, “give a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth.”5 For an artist, their art is, of course, their mask. But the paradox in Wilde’s comment is that while an artist hides behind their art as cover for self-revelation, for that art to endure, it has to be honest. An artist, especially a great artist, can’t help but reveal their inner truths in their art — regardless of how much they might attempt to mask it.

In this two-part episode, we’ll continue exploring the credibility of the lovers possibility by looking at the art of Lennon/McCartney — specifically the songs they've written, together and separately.

I realise some of you are also probably still nervous about the other major objection to the possibility that Paul and John were a romantic as well as a creative couple — that if that’s the case, it’s their story to tell or not tell, and it can't become part of the story of The Beatles until and unless they choose to tell it. But while that objection might seem like a clear, bright line issue, in this case it’s actually not. So once again, I ask for your patience and trust that even though it might not seem like it, we’re doing things in the order they need doing. And the next thing to do is to take a closer look at the music of Lennon/McCartney.

That this episode is long enough to require two parts isn’t meant to imply that the credibility of the lover's possibility rests only — or even mostly — on John and Paul’s lyrics. Hopefully, you’re seeing from the prior episode that there’s considerable support for the lovers possibility outside of their songs.

It’s more that untangling the traces of the lovers possibility in the music of Lennon and McCartney will take a bit of time. Art by its nature deals in metaphor, symbolism and allusion, playing with reality in order to show us a truer reality. And this is true even if we weren’t dealing with world-class lyrical tricksters who revel in wordplay, subtext and double — and even triple — meanings. And all of that is in play here, because obviously, if they did write these songs for and about one another, then those traces weren’t necessarily meant to be found by anyone other than the two of them.

Obviously, for two artists who communicated with the world through song, their songs carry a lot of weight, when it comes to understanding their relationship. Understanding the art helps us to understand the artist — and understanding the artist, in turn, helps us understand the art.

Who we love, who we desire, who breaks our heart and who heals it, is fundamental to the experience of being human, and to who we are. Love is the raw material of much of our civilization’s art, and certainly most of our civilization’s music — and especially when the artists in question are iconic in part because of their songs of love and longing, and for the intensity of their relationship with one another as they wrote those songs.

If there is truth to the lovers possibility, there seems little doubt we’ll find much of that truth in the songs of Lennon/McCartney.

Understanding an artist by studying their art isn’t an especially startling concept — but you might be surprised at just how very much, historically speaking, the mainstream Beatles world does not want to do this when it comes to Lennon/McCartney. Until fairly recently, mainstream Beatles writing has, for the most part, refused to consider the possibility that John and Paul might have written any songs at all about their relationship, other than a couple of too-obvious-to-ignore angry and bitter breakup songs.

It’s odd, to say the least — this insistence that when it comes to understanding the intimate, complex relationship of the most important songwriting duo in history, there’s nothing to be gained in looking at the songs they wrote, and that John and Paul only wrote a handful of poison pen songs about one another.

Except, of course, it’s not odd at all when we factor in the fear and confirmation bias we talked about in the prior episode. After all, the best way to not find something you're afraid to find is to decide it’s not there in the first place.

In my experience, the “proof” most often given that John and Paul didn’t write for and about one another is that if they had, it would be easy to identify those songs. After all, it’s easy to tell that “How Do You Sleep?” and “Too Many People” and “Dear Friend” are about and for one another — if for no other reason than that John and Paul have explicitly told us so. And since those songs are the only ones they’ve explicitly said are for and about each other, then that must be all there is. Case closed.

You might notice already that this is a deeply flawed line of reasoning — and if you ever manage to get one of those Grail-phobic mainstream Beatles writers alone without their dog-eared copy of Revolution in the Head6 to muddle their minds, I suspect they’d admit as much. If John and Paul were involved in a hidden love affair and if they did write about that love affair in their songs, they’re obviously not going to share that information with a journalist or a biographer — hence the key word “hidden.”

As to whether the traces of that love affair are easily seen in their songs — well, that depends mostly on who’s looking.

Like the photos and film footage we considered in the prior episode, seeing the lovers possibility in the songs of Lennon/McCartney requires fluency in the language of the Grail. And noticing the subtle traces of a love affair in lyrics requires the ability to recognise lyrical subtext, as well as the symbolism and metaphor that gives a lyric a deeper meaning beyond what’s visible on the surface — none of which are traditionally in the skill set of even the best journalists, biographers and historians.

This isn’t in and of itself a criticism, mind you. Journalists, biographers and historians tend not to come equipped with those skills (though again, maybe they ought to, given that lyrics are such an important part of pop music). And we tend to be reluctant to venture into territory where we don’t feel confident, which is probably a good thing when it comes to this story.

But the problem with the journalistic method of "ask and write it down" when it comes to song interpretation is that when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Asking an artist what their art is about and then taking them at their word is a poor way to understand art — because it limits our understanding of that art to what the artist is consciously aware of, and perhaps even more, what that artist is willing to reveal. All of which is to say that if the art has any depth to it at all, “ask and write it down” is probably not enough to understand its truth.

And of course, “ask and write it down” is especially useless when it comes to understanding the art of Lennon/McCartney, the merry pranksters of wordplay, deception and double meaning — who tend to be much more interested in letting us discover meaning in their art rather than spoiling the game by telling us what’s actually there.

But of course the problem is that the games the Fabs play with their lyrics inspire people to play their own games right back.

The reluctance to consider that John and Paul may have written love songs for and about one another isn’t helped by the history of people reading bizarre and often truly appalling things into Beatles lyrics, sometimes with extremely unfortunate results — the most notable examples being the “Paul is dead” hoax, and far far worse, the horrific case of Charles Manson, who delusionally believed that secret messages in The White Album included instructions to start a race war.

These high-profile examples of a few people getting it so very wrong have given the mainstream Beatles world a handy excuse for dismissing the possibility of any subtextual meanings in the lyrics of Lennon/McCartney. Instead, Beatles lyrical interpretation is largely seen as a parlor game, nothing more than stoned college students playing records backwards in their dorm rooms looking for secret Fab messages, or conspiracy theorists holding knife blades to the Sgt. Pepper drum to read “HE DIE” in the reflection—

—and yes, I tried it and yes, it’s really there and yes, it’s interesting, and no, it doesn’t prove anything at all other than that The Beatles liked to mess with our heads, which we already knew — and which of course is why Fab lyrical interpretation is an especially risky proposition.

The truth of an artist might be found in their art, but Lennon and McCartney love to turn us on and always have — from the double-meaning play on words in their second single, “Please Please Me” all the way through to their final song, the first-ever hidden track, at the end of Abbey Road.

John and Paul aren’t much help, either, with their occasional claims that the wordplay and imagery in their songs doesn’t mean anything at all, and that those of us who look for meaning are wasting our time chasing after illusions put there just to throw us off track.

But even given all the monkey business with their lyrics on both sides, it’s notable that despite our acknowledgment of their genius, the Beatles community as a whole tends to be very bad at giving John and Paul the artistic benefit of the doubt when it comes to their songs having a deeper meaning.

This is especially puzzling given none of those doing the writing-off have anywhere near the mastery of language of Lennon and McCartney. It’s a bit like an amateur mathematician dismissing string theory in particle physics on the grounds that since they don’t understand the maths, the theory doesn’t make sense.

But here’s the thing — we can’t have it both ways, and neither can John and Paul.

We’re either going to acknowledge that Lennon/McCartney — the writers of “A Day in the Life” and “Eleanor Rigby” and “She’s Leaving Home” and the Abbey Road medley — are history’s most influential and accomplished songwriting team and that their songs reflect that genius, or we’re going to decide that their songs are one-dimensional and superficial, meaning only what they appear to mean on the surface and sometimes not even that — in which case why are we even bothering to study them in the first place, because both of these things by definition can’t be true.

And if Lennon/McCartney are what they indisputably are, in terms of influence and mastery of craft — even without factoring in their mythological importance — then by definition the art they created is going to include complexity of language, subtext and multiple layers of meaning — including meaning that we have yet to discover and meaning we may never discover.

And if there is truth to the lover's possibility, and if they did write those love songs for and about one another, then both of them would obviously be highly motivated and highly practised at leveraging the full weight of their genius — not to mention their answers in interviews — to hide the traces of the lovers possibility in those songs from the mainstream and direct attention away from meaning in their lyrics.

They are, in short, going to make us work for it.

Given this tendency to underestimate the complexity of their songs, let’s do a quick primer on Lennon/McCartney’s mutual love affair with the English language.

“Words are flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup. They slither wildly as they slip away across the universe.”7 — John Lennon

It’s well-known that both Paul and John grew up loving clever wordplay — most notably in the works of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, James Thurber, Ogden Nash, and in the art of Ronald Searle.

This love of wordplay is, of course, obvious in their art — in Paul’s poetry and John’s books, and of course,through their music, together and solo. What’s less well-known is that both Paul and John grew up in families in which words were especially valued — and Paul in particular grew up in a family that loved to play with words.

Here’s Paul in 2022 (edited for length)—

“My own father’s influence extended well beyond music. He gave me a love of words that may first have been apparent when I was in school. It was hard as a kid not to be aware of the way he could juggle words or how much he loved crossword puzzles. It’s a very Liverpool thing to say silly things, but he carried it a good step further, and it took some doing to keep up with the subtleties of his jokes and puns. As a boy, I did not realise that I was absorbing my father’s love of words and phrases, but this, I believe, was the start of it all for me. Musicians get only twelve notes to work with, and in a song, often you use only about half of them. But with words the options are limitless, so it dawned on me that I, just like my dad, could play with them. It was as if I could toss them up in the air and then see when they all came down how language could become magic.”8

Paul’s father regularly engaged a young Paul and his brother Mike in solving the daily crossword puzzle, and challenged them to look up words in the dictionary that they weren’t familiar with. Paul’s cousin Bert Danher was a successful creator of crossword puzzles for the leading newspapers of the time, including the London Times and The Guardian, and credits Paul’s father Jim McCartney for inspiring his love of words.9 Paul’s brother Mike was a member of the absurdist Sixties comedy troupe The Scaffold. And of course, Paul went on to become Paul McCartney.

John’s Aunt Mimi probably didn’t like to play with words per se, but she was by all accounts an unusually devoted reader — somewhat unusual for a middle-class woman of her generation.10 And while I’m sceptical of John’s claim that as a child, he read the complete works of Winston Churchill, Mimi’s love of reading and her middle-class economic status meant that John grew up in a house that had what for the time would have been a better-than-average library, and no doubt Mimi’s encouragement to make use of it.

John and Paul also had an education that prioritised the written word. I didn’t realise until I talked with people in Liverpool who’d known John and Paul as teenagers that both the schools John and Paul attended — Quarry Bank and the Liverpool Institute for Boys — were among the top college-prep schools in the north of England, and that the Liverpool Institute in particular was regarded as one of the finest schools in England.

Paul’s literature professor at the Institute was Dr. Alan Durband, a noted scholar of yet another great wordsmith, William Shakespeare. Professor Durband saw linguistic talent in a young Paul McCartney and encouraged him to pursue a career as a literature professor. Paul has credited Dr. Durband as the first person to turn him on to the beauty and power of language — through the sexy stories of Chaucer.11

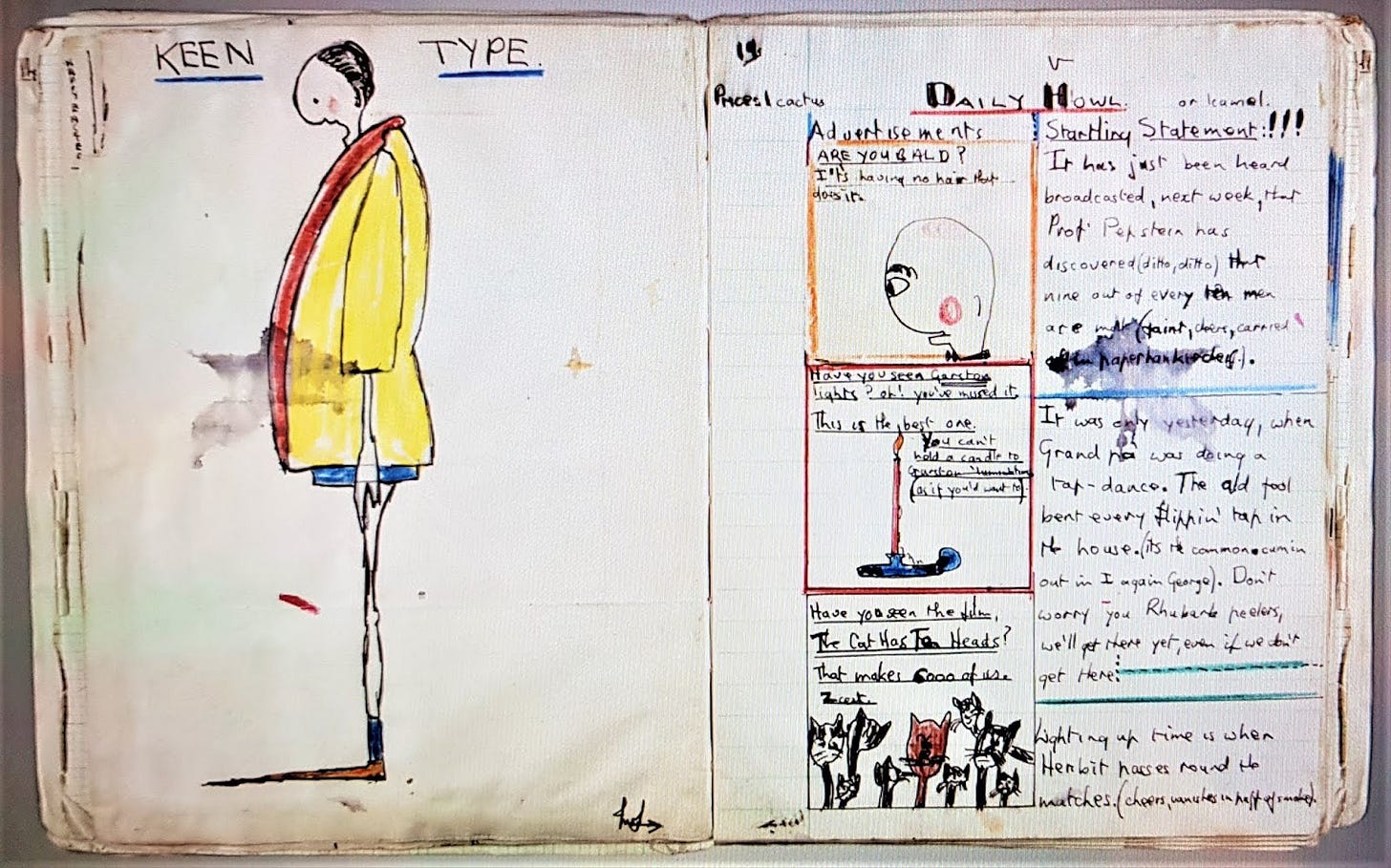

And of course, I doubt anyone loved playing with words more than John. His lifetime love affair with language love showed itself less In his academic work than in “The Daily Howl” — the underground ‘zine he wrote during his Quarry Bank years.

Not surprisingly, Paul and John's mutual love of language and wordplay extended into their taste in music. From the earliest days, when they were both drawn to songs by other artists that included clever wordplay, in particular the songs of Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly — the poets of early rock-and-roll.

Fast forwarding ahead a bit, here’s Victor Spinetti, who played the TV producer in A Hard Day’s Night, talking about The Beatles’ interest in great literature and thought (edited for length) —

“The Beatles were inquisitive. They wanted to know stuff... John had been reading a book about Carl Jung and got really interested, so we found ourselves comparing the Jungian interpretation of dreams with the Freudian interpretation of dreams. Another day it was the writing of Christopher Marlowe. Really, the main thing was the ceaseless inquiring.”12

And Beatles press agent Tony Barrow tells this story from the 1966 tour—

“On the Tokyo flight [The Beatles] opted for Dictionary, a word game the group claimed to have invented, but in reality probably borrowed from something they’d seen on TV... Mal would produce a pocket dictionary and kick off the game by choosing an obscure word. Everybody would write down a made-up definition, the crazier the better and, after they had all been read out, each player would vote for the one he thought was correct.”13

This might seem inconsequential, but it’s not. There are a lot of things an overworked, exhausted rock-and-roll band might be expected to do on an international flight — sleep, mostly, but also drink, play cards, gamble and swap jokes and tour gossip, and perhaps other, spicier activities with the flight attendants, to name a few options. Instead, The Beatles chose to play a word game — and more than that, a word game that rewards the creative and deceptive use of words. And if Mal was carrying around a pocket dictionary, and given it was a game they claimed to have invented,14 the Dictionary Game was clearly more than a one-time distraction.

There’s more, of course. John published three books of absurdist prose. Paul published a book of often-absurdist poetry. Paul and John helped to fund the opening of the Indica Bookshop and the underground magazines International Times, Oz and Ink. And Paul funded the establishment of an independent recording studio dedicated to spoken word poetry that later morphed into the experimental record label Zapple. They maintained friendships with beat poets Allen Ginsberg and Royston Ellis. John read widely all of his life and wrote multiple songs based on absurdist and esoteric books,15 and Paul has said that he was influenced by absurdist playwright Alfred Jarry on songs like “Penny Lane” and “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.”16

John and Paul, to put it simply, grew up loving words and even more so, loving the creative and clever ways in which words can be used. And this love, of course, carries over into their lyrics.

Great art demands complexity and layers of meaning, and since we’re indisputably in the hands of great artists, when it comes to the lyrics of Lennon/McCartney, it’s far safer and wiser to presume complexity and layers of meaning as the default, rather than the exception. And we might also do well to have the humility to consider that if we’re not seeing that complexity, it might be because we’re not seeing it and not because it’s not there.

What I’m suggesting with all of this is that given the artistic stature and influence — mythological and otherwise — of Lennon/McCartney, it’s past time to give serious attention to their lyrics as the complex, layered, sophisticated works of art that they are.

“The idea is that what I’ll leave behind me will be music, and I may not be able to tell you everything I feel, but you’ll be able to feel it when you listen to my music. I won’t have the time or the articulation to be able to say it all, but if you enjoy composing you say it through the notes.”17 — Paul McCartney

Give a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth. The art of Lennon/McCartney — often cloaked in double-meanings, complex wordplay and absurdism — contains mask upon mask upon mask.

But no matter how mind-bendy John and Paul get in the games they play with our brains, the fact remains that words still mean what they mean. There’s a hard limit to how much any artist can distort the truth in their art before the art itself becomes a lie. And even at their most distorted, the art of Lennon/McCartney is never a lie.

That truth is why we’re intimate by instinct18 with them in the same way as we are with Shakespeare, and for the same reason. This is the music that changed our world — for the extreme better. It couldn't have done that if it wasn’t rooted in truth, however much that truth is often hidden behind mischief and wordplay. We can feel that truth even more than we can hear it.

Paul and John have insisted that many of their songs are meaningless, but — in typical trickster fashion — they’ve also told us that everything in their songs means something, and that their music is the place to look for their truth.

For example, in 1969 Life magazine asked Paul about the breakup. Paul’s answer was simple— "What I have to say is all in the music. If I want to say anything, I write a song."19

And here’s Paul in the foreword to his 2022 book The Lyrics—

“More times than I can count, I’ve been asked to write an autobiography, but the time has never been right. Usually I was raising a family or I was on tour, which has never been an ideal situation for long periods of concentration. But the one thing I’ve always managed to do, whether at home or on the road, is write new songs. Some people, when they get to a certain age, like to refer to a diary to recall day-to-day events from the past, but I have no such notebooks. What I do have is my songs — hundreds of them —which serve much the same purpose. And these songs span my entire life, because even at the age of fourteen, when I acquired my first guitar in our little house in Liverpool, my natural instinct was to start writing songs. Since then I’ve never stopped.”20

And further down the page, Paul continues with—

“Over time I came to see each song as a new puzzle. It would illuminate something that was important in my life at that moment, though the meanings are not always obvious on the surface. Fans or readers, or even critics, who really want to learn more about my life should read my lyrics, which might reveal more than any single book about The Beatles could do.”21

I don't know that it’s possible to be more clear than Paul is being here that it’s the songs we need to look to for the truth of his life.

As for John, it’s fairly obvious even without him saying so that he virtually always wrote confessionally.

And when Rolling Stone writer Jonathan Cott asked John how he felt about people seeing meaning in Beatles songs that wasn't there, John answered simply, “It is there.”22

To offer just a few examples of John’s confessional writing, he wrote about his lifelong battle with depression in “Help!” “I’m Only Sleeping,” “Good Morning, Good Morning,” “Yer Blues,” “I’m So Tired,” and “Whatever Gets You Through the Night.” He wrote about his struggle with insecurity and low self-esteem in “Nowhere Man,” “I’m a Loser,” “Crippled Inside,” “Scared” “Isolation” and “Nobody Loves You When You’re Down and Out,” and about his spiritual search and spiritual crisis in “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “God” and “Remember.” He wrote about his struggle with heroin addiction in “Cold Turkey” and about his struggle with fame in “I Don’t Want To Face It” and “Watching the Wheels.” He wrote about his difficult childhood in “Working Class Hero” and about losing his mother in “My Mummy’s Dead,” “Mother” and “Julia” (and possibly in all of his Yoko songs, which we’ll get to later in this series when, well... when we get to all of that.)

John tells us about his need to write confessionally in — of all places — the same Rolling Stone interview with Jann Wenner in which, as we talked about in the prior episode, he admitted he lied his ass off throughout, before telling us where we ought to be looking for the truth (edited for length)—

“I always wrote about me when I could. I didn’t really enjoy writing third person songs... But because of my hang-ups and many other things, I would only now and then specifically write about me. Now I wrote [Plastic Ono Band] all about me and that’s why I like it. It’s me! And nobody else. It’s real, that’s all. I don’t know about anything else, really, and the few true songs I ever wrote were like “Help!” and “Strawberry Fields.” I can’t think of them all offhand. They were the ones I always considered my best songs. They were the ones I really wrote from experience and not projecting myself into a situation and writing a nice story about it. I always found that phony, but I’d find occasion to do it because I’d be so hung up, I couldn’t even think about myself.”23

In 1980, John told interviewer David Sheff that—

“These stories about boring people doing boring things: being postmen and secretaries and writing home. I’m not interested in writing third-party songs. I like to write about me; ’cuz I know me.”24

And here’s John in 1973—

“People’s expressions and feelings come out in their work whether they want it to or not. So I always express myself directly, or [in the] language of the streets, and other people don’t.”25

I suspect that when John adds, “other people don’t,” he’s talking about Paul — because John has a history of being frustrated with Paul’s less-than-direct way of writing his own life into his songs. Here’s John again in 1980—

“As I read the other day, [Paul] said in one of his ‘fanzine’ interviews that he was trying to put some distance between The Beatles and the public— and so there was this identity of Sgt. Pepper. Intellectually, that’s the same thing he did by writing “He loves you” instead of “I love you”. That’s just his way of working.”26

and again in the same interview —

“I think everything that comes out of the songs – even Paul’s songs now, which are apparently about nothing – the same way as calligraphy shows and your handwriting shows you everything about yourself. Or [Bob] Dylan too. Dylan might try to hide in a subterfuge of clever, Allen Ginsberg-type words, or hippie words, but it was always apparent, if you look below the surface, what is being said. Resentfulness, or love, or hate. And it’s apparent in all work. It’s just harder to see when it’s… written in gobbledy-gook.”

These quotes from John are particularly intriguing because notice how he’s saying Paul’s songs are “apparently” about nothing — before going on to say that he’s aware they mean quite a lot, just disguised in “gobbledy-gook.”

And as we’ll see, it’s possible that Paul’s “gobbledy-gook” songs that John recognised as having meaning were intended to have meaning only for John. It’s yet another example of how lack of fluency in the Grail makes it easy to miss that John saying Paul’s songs “apparently mean nothing” isn’t actually a slag, but a compliment — albeit a backhanded one — and also perhaps a clue.

As John has observed, Paul tends to write about his life more obliquely and John tends to do so more directly — or at least so it seems. But nonetheless, the vast majority of their songs, together and otherwise, are self-evidently — and by their own reports — intentionally autobiographical.

As for Paul writing about his own life in his songs, John’s right when he says that’s a bit more complicated. Unlike John, who sometimes expressed his feelings a bit too freely for his own good outside of song lyrics, Paul has said many times that he struggles with expressing his feelings outside of songs.

Here’s Paul in 2000, talking about his paintings, but really in general about his creative process—

“In the end that is based on the theory that whatever you do, there must be some sort of meaning. There will be some sort of meaning, because it is like you are unloading your mind’s computer, you are printing out your psychic computer, whether you know it or not.”27

Here’s Paul talking with Howard Stern in 2021—

“...it’s kind of nice because once you finish [a song], it’s like you’ve had a psychiatric session and you’ve told all of your secrets and now you feel much better. You’ve got rid of it, you know but into something nice, into something you can then go, oh, here’s all my feelings in a bundle. Let’s record it.”28

And here’s Paul again—

“When I write, I'm just writing a song, but I think themes do come up. You can't help it. Whatever is important to you finds Its way in. I saw someone writing about an artist, a painter, and he says, ‘every painting a person does is of themselves.’ Even if it's a portrait of his wife, Himself gets in it. You really can't help it, because it's you making all the marks on it. I think it's similar with songwriting. Whether you like it or not, even if you're trying to write a song for a James Bond film, something of what you feel always ends up in it.”29

And because we’re going to need a lot of these to counter all those times both of them also insist that none of it means anything, here’s one more — Paul in a 2016 interview, answering a question about how it feels to reveal so much of himself in his songs—

“It’s funny because just in real life, I find that a challenge. I like to sort of, not give too much away. Like you said, I’m quite private. Why should people know my innermost thoughts? That’s for me, they’re innermost.”30

Of course, Paul is under no obligation whatsoever to share his innermost thoughts with anyone, least of all us. But ultimately, as he acknowledges — and as with all great artists — he can’t help it. A colleague of mine in the world of underground Beatles studies once said of Paul McCartney that his primary contradiction is that he’s gripped with an insatiable compulsion to share his self expression with the world, but at the same time, he has a great fear of being known.31

Here’s the rest of Paul’s “innermost thoughts” BBC interview answer:

“In a song, that’s where you can do it. That’s the place to put them. You can start to reveal truths and feelings. You know, like in ‘Here Today’ where I’m saying to John “I love you”. I couldn’t have said that, really, to him. But you find, I think, that you can put these emotions and these deeper truths – and sometimes awkward truths; I was scared to say “I love you”. So that’s one of the things that I like about songs.”32

Much of Paul’s songwriting concerns itself with this struggle to express his feelings, and — as in the quote we just heard — that struggle seems centred around Paul’s specific regret at not having been able to fully express his love to John.

Later in this episode, we’ll return — with sensitivity and respect — to this often-voiced regret of Paul’s. Not out of any voyeuristic desire to invade Paul’s innermost thoughts, but because it seems to be one of the central, defining themes of his songwriting — which means it’s not possible to ignore it and still talk with any kind of coherence about either Paul as an artist or his relationship with John.

Paul’s “I couldn't tell John I love him” regret is also, obviously, directly relevant to the credibility of the lovers possibility. This regret is often offered — even in the Beatles studies counterculture — as conclusive proof of the theory we talked about in the prior episode — that John was in love with Paul, but that Paul either didn’t realise or couldn't admit he was in love with John until it was too late. But as we’ll see later in this episode, if Paul’s regret “proves” anything relative to his relationship with John, it might be the opposite.

For now, let’s note that Paul has also frequently compared songwriting to therapy.

Here’s what he said about that in his 1997 quasi-memoir, Many Years From Now—

“I like writing sad songs, it's a good bag to get into because you can actually acknowledge some deeper feelings of your own and put them in it. It's a good vehicle, it saves having to go to a psychiatrist. Songwriting often performs that feat, you say it but you don't embarrass yourself because it's only a song, or is it? You are putting the things that are bothering you on the table and you are reviewing them, but because it's a song, you don't have to argue with anyone.”33

And here’s Paul in 2019—

“I think it’s good when you’re in a dark period, the good is [the song’s] your psychiatrist, it’s your therapy, and you know we have many tales – anyone who writes has. Going away when you’re really upset about something and putting it in your song – you come out of that cupboard, toilet or basement and go, “I really feel better.” You’ve actually exorcised the demon. So it is one of the great joys of songwriting.”34

Here’s Paul in 1982, talking about “Here Today,” his official song for John on the “Tug of War” album—

“Songwriting is like psychiatry; you sit down and dredge up something that’s inside, bring it out front. And I just had to be real and say, John, I love you. I think being able to say things like that in songs can keep you sane.”35

Paul couldn't make it more clear that songwriting — and his art in general, including his paintings — is where he feels safe (well, safer) expressing and working through feelings he struggles to express or work through in any other way. And virtually the only example he offers of this struggle is his regret about not having told John he loved him.

We’ll come back to that soon, but for here, what’s important is that Paul’s art — his songs and his paintings— are by far the most reliable window we have into his innermost thoughts.

And that means that what Paul says his songs mean is less reliable than looking for meaning in the songs themselves. If songs are where Paul feels safe sharing his innermost thoughts, he's obviously not going to then turn around and tell an interviewer what those songs are about — that would defeat the whole purpose of putting it in a song. And if it’s his innermost feelings about a hidden love affair, even more so.

Because of this, I think it’s safe to say that if not for his music, we’d know very little about Paul McCartney as a person. But we do have his music, and he’s told us that the truth of his life is to be found there.

The point here is that, while it’s wise to take what both Paul and John say about the specific meanings of individual songs with a healthy dose of scepticism, there’s no reason to doubt them when they tell us that the truth of their lives is in their songs.

So then, is it ridiculous to suggest that John and Paul might have written more than just those angry breakup songs about each other? And that they might have written not just about one another, but that they might have used their songs as a way to express their feelings to each other? That they might, like the tragically thwarted lovers Pyramus and Thisbe, have used their songs as a way to whisper through the many walls that separated them in the culture they lived in?

And that if they were in love — which as we talked about in the prior episode, they seem clearly to have been — that many and maybe even most of their love songs might have been written for and about one another? And that they likely would have hidden their musical conversation to one another in their mutual, lifelong love of absurdism, wordplay and double-meaning?

I hope by now the answers to these questions are self-evident.

Given that the nature of art is to reveal the artist, given the outsized influence and presence John and Paul have in each other’s lives and the unusual-by-any-standard intensity of their bond, given John’s need to be confessional in his songs and Paul’s need to use his songs as his primary outlet for therapy and self-expression, it’s far more improbable that they wouldn’t have written about one another — not once or twice, not occasionally, not in a handful of obvious, impossible-to-ignore breakup songs — but throughout their entire creative careers, right up to today. It defies common sense and what we know about their relationship and their creative process to insist otherwise.

And given all of this, if John and Paul were indeed lovers, it seems without question that love affair will reveal itself in their songs — but only if we look with the right gaze and hear with the right ears.

And that brings us to what might be the strongest support for the credibility of the lovers possibility, at least relative to their music — that the emotional arc of their songwriting seems to follow the emotional arc of their relationship with each other far more closely than it follows their relationships with their public romantic partners.

Let me say that again because it’s important — and it’s a little tricky to describe in words:

The emotional arc of John and Paul’s songwriting, together and separately, seems to follow the emotional arc of their relationship with each other far more closely than it follows their relationships with their public romantic partners.

Confirmation bias and fear of softness has made us shoehorn the emotional arc of their songs to fit their relationships with their public romantic partners — but it doesn't fit any more than the glass slipper fits Cinderella’s stepsisters. The emotional arc of their songs does, however, fit the arc of John and Paul’s relationship with each other like— well, a glass slipper on the foot of the real princess.

When John and Paul are in a good place together — or at least seem to be from what we know — their songs reflect that good place, regardless of what seems to be happening with their other relationships. When their relationship with each other appears to be more difficult, their songs reflect that, too, regardless of how good their relationships with their other partners seem to be at the time.

I say “seems” because there’s obviously a hard limit to how accurately we can follow this emotional arc relative to their songs. The vast majority of what goes on between two people in a relationship — romantic or otherwise, hidden or otherwise — isn’t visible to the public, even when those two people are among the most written-about couples in history.

Paul and John’s relationship spanned over two decades — and in a very real way continues into the present day. And especially given how notably — and perhaps tellingly — little either of them has shared about that relationship, we’ll likely never know more than a tiny fraction of what happened between them in private — which is why we’ll likely never recognise more than a tiny fraction of the inside references to shared memories that they probably wrote into their songs. And of course, that’s how it should be. Those are private memories only John and Paul are meant to know about.

But despite the challenges, we do know quite a bit about the arc of their relationship — though perhaps not quite as much as we think we do. And given what we do know, it’s this overall pattern, more than any individual song, that offers the best musical credibility for the lovers possibility — in the same way that the support for the lovers possibility in the research is found in the cumulative weight of that research rather than in a single data point.

Exploring this parallel arc in their music will, of course, take time. It’s certainly more than we can do even in a two-part episode. And that’s part of what we’ll do when we re-tell this story in the next part of the series.

So with all of that as backdrop, let’s now — finally — turn our attention to some actual songs.

“'Thou envious wall why art thou standing in the way of those who die for love?”36 — Ovid, Metamorphoses

In writing this episode, the hardest part has been resisting the temptation to talk about every single song that contains support for the lovers possibility, because every one of them potentially has something to teach us about the complex relationship between John and Paul.

Tragically, I’ve been forced to rein in my temptation, because talking about every possible “JohnandPaul” song in a single episode is wildly impractical, because there are a lot of them — enough so that my fab research assistant Robyn created a searchable index so I could reference them more easily.37 And more than that, most of the songs that seem to have been written for and about one another require a significant amount of context to be able to see why they’re ‘JohnandPaul songs,’ and that expanded context will need to wait till the next part of this series when we re-tell the story.

There are particular challenges in looking at Beatles songs for traces of the lovers possibility.

First, the songs of Lennon/McCartney have become so deeply woven into the fabric of our lives, that it’s difficult to set aside our confirmation bias and hear with fresh ears and a different perspective songs we’re so familiar with that they’ve become part of who we are.

And second, when John and Paul are writing as Lennon/McCartney, it’s difficult and maybe even impossible to separate out their individual voices and know for sure who’s saying what to and about who. Despite the widely held convention of separating their Beatles songs into “John songs” and “Paul songs” based on who the primary composer was, the reality is that in an intimate, long-term creative collaboration, there’s really no such thing as a song that’s entirely the voice of one of the partners.

We’ll talk about that in this week’s Rabbit Hole — because this near-universal convention, even in countercultural Beatles studies, of dividing their creative work into ‘written by John’ songs versus ‘written by Paul’ songs is part of the wounding in the story.

Given these challenges, we’re going to focus not on their Beatles work, but on their post-breakup solo songs. Most of us are less familiar with Paul and John’s solo work, especially the non-singles. So it’s easier to hear those songs with new ears. And because Paul and John were writing separately in the ‘70s,38 the conversation between them is thus easier to hear.

Also, the traces of the lovers possibility seem to be closer to the surface in their ‘70s work than in their Beatles work — even without a deep knowledge of the context in which the songs were written — and thus those traces are easier to see without a lot of context. This might sound counterintuitive — that we’d be able to see the connection between them more clearly during a time when they were so very dis-connected, in the first years after the breakup when their estrangement was at its peak, and the walls between them were at their most formidable. But it does seem to be the case.

Paul confirmed this, when he acknowledged in 2004 that during the breakup and its aftermath, “we weren’t speaking at all by that time. So the only way we could communicate our feelings was through writing songs.”39

This separation was more than just emotional, it was physical.

Beginning in 1971, for the first time since they’d met as teenagers, John and Paul weren’t breathing the same air. Instead, they were a literal ocean apart — Paul in the UK and John stranded in America due to immigration troubles as a result of his drug conviction.40 Communication between them that had always been logistically if not psychologically, easy, now wasn’t. Letters were slow with no guarantee of privacy, international phone calls difficult to coordinate across time zones, and also maybe not private (especially given the FBI’s wiretap on John’s phone). Visits were even harder, even minus the hurt feelings of their estrangement, and because Paul’s own drug conviction may also have made it hard for Paul to come to the US for a visit.

But whatever else stood between them, it speaks to the depth of their bond that their conversation in song — their musical “whispers through the wall”— didn’t stop even during the worst of their estrangement. And perhaps in part because of those “whispers through the wall,” by 1973 tempers had cooled and both John and Paul seem to have been feeling their way towards one another again.

It’s during this period of regret and reconciliation that the traces of the lovers possibility become much easier to see in their songs. Perhaps, even after they started speaking again, the literal and emotional distance between them after the breakup made their need to communicate with one another through song more urgent.

And given their estrangement and the breakdown of their usual ways of communicating, both of them may have felt a heightened need to make sure the message was received and not misinterpreted. That may have meant putting that message closer to the surface, to be sure it wouldn’t be missed by its sole intended recipient.

So in this two-part episode, we’re going to focus mostly in on two songs from this post-breakup period of their relationship, when they’re just on the cusp of reconciliation, speaking again but still separated by physical distance — “No Words” from Paul’s 1973 album Band on the Run, and “Bless You” from John’s 1974 album Walls and Bridges. And then for those of you who want to explore further, next week’s Rabbit Hole will offer a more detailed analysis on some of the songs we won’t have time to talk about in the main episode.

Before we dive in, a reminder that I’m not suggesting these two songs — or any of their songs, for that matter — by themselves prove anything relative to the lovers possibility. Lyrical interpretation doesn't work quite that way. Art is too fluid, too subject to the mysteries of the creative process, to offer solid conclusions based on its interpretation alone. And the art of Lennon/McCartney, with its wordplay and misdirection, especially so — which is fine, because although it might seem like it sometimes, we’re not out to “prove” anything here, even if we had the ethical standing to do so, which as we’ve already talked about, we don’t.

What we’re doing by looking more closely at the music of Lennon/McCartney is continuing to counter the objection that the lovers possibility isn’t credible, and that that’s why it shouldn't be included in mainstream Beatles writing.

All of that said then, let’s look at “No Words,” a song in which the traces of the lovers possibility are so obvious it’s hard to understand how even a Grail-phobic Beatles writer can fail to notice them.

And yet.... they did, and still do.

I left for the toy store

I bought my self a whole new situation

asking the future for you

wishing the breeze would be mine

chasing the running stream

hoping you’d be tall in the grass41

— Paul McCartney (Toy Store, poem)

To talk about “No Words,” we now need to go back to Paul’s apparent lifelong struggles with expressing his feelings — and especially his struggle with saying “I love you.”

As a reminder, here’s what he said in 2016—

“It’s funny because just in real life, I find [sharing my feelings] a challenge. I like to sort of, not give too much away. Like you said, I’m quite private. Why should people know my innermost thoughts? That’s for me, they’re innermost. But in a song, that’s where you can do it. That’s the place to put them. You can start to reveal truths and feelings. You know, like in ‘Here Today’ where I’m saying to John “I love you”. I couldn’t have said that, really, to him. But you find, I think, that you can put these emotions and these deeper truths – and sometimes awkward truths; I was scared to say ‘I love you.’ So that’s one of the things that I like about songs.”42

And here’s Paul in 2013 —

“You can actually say, “I love you,” to someone, but it’s quite hard. And so that’s why it’s usually easier when you’re a bit drunk. It’s like ‘Here Today’, which was for John, and there is the line, (sings) “Du du du du du du du, I love you,” and it is a bit of a moment in the song.”43

As we talked about earlier, it seems clear from this quote and many others like it over the years44 that for Paul, expressing his emotions and especially his love, is a central struggle — and perhaps even the central struggle — in his life.45 At the very least, it’s the struggle he’s most willing to share publicly — or perhaps the struggle he can’t help but share publicly, given how frequently he brings it up in his interviews and more importantly, in his songs.

And when Paul talks about his struggle to share his feelings, you may have noticed the example he most frequently brings up is that he couldn't tell John he loved him.

This isn’t me cherry picking the interviews in which he chooses John as the example. Other than occasional later references to having initially struggled to tell his wife Nancy that he loved her, John is the only example from his own experience that Paul offers when he talks about having trouble saying “I love you.” And more than that, John is the only person Paul brings up when he shares his regret at not having been able to say “I love you.”

When Paul links his struggle to express his feelings to his relationship with John, he seems to be revealing, indirectly but unambiguously, that being unable to fully express his love to John is one of — and perhaps the — central regret of Paul’s life.

Paul brings this regret up frequently enough that by now, most of us are used to Paul talking about his love for John. But it’s an example of our collective lack of Grail fluency and the tendency to see what we expect to see, that most people assume the love Paul is talking about relative to John is brotherly, rather than romantic, when every indication says otherwise — including and especially Paul’s songs.

The truth of an artist’s life can’t help but be reflected in their art — and Paul has told us that he uses songwriting as therapy for things he has a hard time expressing and dealing with otherwise. If Paul’s regret at not having expressed his love to John is a central regret in his life, and if Paul uses his songwriting as therapy, then it follows that we ought to be able to find that regret as a frequent theme in Paul’s songs.

And because his struggle to express his love to John is virtually the only example of this regret that Paul talks about in interview, it’s an extremely safe bet that when a struggle to express love or a regret at not having been able to express love appears in a Paul McCartney song, that song is about John.

During the Lennon/McCartney years, Paul’s struggle with expressing his feelings barely appears in their lyrics, and when it does, it’s in a far less urgent form — more of a background issue than a central conflict in his life.

Here it is in an unreleased song from the Hard Day’s Night sessions, “That Means A Lot”46 —

Love can be deep inside

Love can be suicide

Can't you see you can't hide what you feel

When it's real?

It’s expressed again through the metaphor of a language barrier in “Michelle,” and again as “The Fool on the Hill” who never shows his feelings. And given Paul’s use of rain as a metaphor for grief in future songs, it’s possibly the theme of “Fixing a Hole” where the rain — aka difficult feelings — are starting to work their way in despite Paul's efforts to keep them out. But when it comes to hiding your feelings and regret songs, that's more or less it during the Beatles years.

But that changes beginning with the breakup, and especially in the early 70s, when John is in New York and they’re at the height of their estrangement — emotionally, creatively and geographically. Because that’s when those “whispers through the wall” between the two of them start in earnest — when Paul said that “we weren’t speaking at all by that time. So the only way we could communicate our feelings was through writing songs.”47

This time period is precisely when the struggle to express love becomes a prominent theme in Paul’s songs. It’s also when — for the first time — his regret at not having found the right words to say “I love you” begins to appear in his lyrics. And if you’re now putting that piece of information together with what might have caused the breakup, well, yes — though we have a ways to go before we’re ready to consider all of that.

Once we know to look for them, these themes of struggle and regret become easily visible in song after song during this time period. Some of the more obvious examples include “Lazy Dynamite” from 1972’s Red Rose Speedway—

Won't you come out tonight

When the time is right

Or will you fight that feeling in your heart

Don't you know that inside

There's a love you can't hide

If we had time, we’d talk about all the other clues to the lovers possibility in that verse, but let’s move on and mention “Power Cut” also from Red Rose Speedway —

I may never tell you

But baby you should know

There may be a miracle

And baby I love you so

And “Let Me Roll It” from Band on the Run, in 197348—

I can’t tell you how I feel

My heart is like a wheel

Let me roll it to you

And perhaps most obviously, in “No Words.”

The title alone tips us off that “No Words” is a struggle with feelings/regret song — and thus very likely to be about John.

Here’s the first verse—

You want to give your love away

And end up giving nothing

I'm not surprised that your black eyes are gazing

You say that love is everything

And what we need the most of

I wish you knew that's just how true my love was

It doesn’t take much fluency in the language of the Grail, and it doesn’t take more than basic knowledge of Beatles history, to know there’s only one person in Paul’s life who wrote and sang the lead vocal on “All You Need Is Love,” (... “love is all we need”...) the anthem of the Love Revolution, in a satellite broadcast to 700 million people around the world, and only one person who had, by the time “No Words” was written, spent the past three years declaring himself to the world’s press as the global spokesperson for love.

If you know your history beyond the basics, though, that reference to “black eyes gazing” might have caught your attention, because John’s eyes were brown, not black.

The simplest explanation is that “black” sings better than “brown” in that line — and it does. But remember, this is McCartney of Lennon/McCartney, and our rules of engagement here are to presume mastery of craft. And that means that we assume they’re not just sticking a word in because it rhymes or sings better. And we’re also assuming layers of meaning.

The next most obvious possibility is that if Paul is indeed looking to send a “whisper through the wall” to John that won’t be heard by the rest of the world, he’s likely to change the eye colour the same way he’d change a pronoun from “he” to “she.”

And this is possible, but given the general lack of Grail fluency in the Beatles world — and the world in general — I’m not sure the eye colour swap was strictly necessary. I suspect Paul could have included John’s birthday and shoe size and dedicated the song to John in the liner notes, and it still would have slipped under the radar of the Grail-phobic music press.49

There’s another possible layer of meaning here, though, that makes the choice of “black” over brown” a bit more interesting. Because of course, “black eye” has at least one other meaning quite independent of literal eye colour.

A black eye is what we get when we’ve been literally punched in the face. And in metaphor, a black eye is what we get when we’ve done something that earns us a metaphorical punch in the face from the world.

“No Words” is on Band On The Run, but it was written in 1972, during the Red Rose Speedway sessions, when the wall between Paul and John seems to have been at its thickest. And in 1972, Paul knows full-well that John is suffering from plenty of cultural, creative and personal black eyes.50

In 1972, John and Yoko’s latest album, the angry, agit-prop Some Time In New York City, was a critical and commercial disaster, putting John in the uncomfortable position of being the least commercially and critically successful of the four Beatles — thus seemingly confirming all of John’s deepest insecurities about his own talent, especially relative to Paul’s.

Paul also probably knew John and Yoko’s peace activism was wearing thin with the public and the media, and that their shenanigans were increasingly viewed as attention-seeking spectacle rather than any sort of effective political action.51 Paul has said that he got updates about what John was up to, and we know he read John’s breakup interviews.52 At the time “No Words" was written, John did indeed want to give his love away and had ended up giving not much of anything.

John’s got some “black eyes” in his personal life in 1972, as well. He’s less than a year away from separating from Yoko for his eighteen-month “Lost Weekend.” And Paul may have heard that the relationship between John and Yoko was not quite as perfect as they’ve made it out to be in public. Since it seems he was kept updated, Paul might even have heard the gossip that John was overhead at a party arguing with Yoko and telling her that, “I wish I was back with Paul.”53

And since Paul probably knows John better than anyone else in the world, he knows John is by nature restless and impulsive, in search of the next new way to beat back his demons. And since his latest attempts are failing, of course John’s looking around to see what else he might try. Of course his black eyes are gazing.

Let’s temporarily skip over the whole “burning love” situation in the middle eight, and look at the last verse—

You want to turn your head away

But someone's thinking of you

I wish you'd see, it's only me,

I love you

Even beyond the struggle to communicate his feelings, this verse is the big “tell.” Because “It’s only me” is shorthand for Paul’s #1 go-to, featured, keystone John story — the one he’s told so many times it’s practically a genre unto itself.

Here’s Paul in May of 1981—

'I didn't hate John. People said to me when he came out with those things on his record about me, you must hate him, but I didn't. I don't. We were once having a right slagging session and I remember how he took off his granny glasses. I can still see him. He put them down and said,"It's only me, Paul." Then he put them back on again, and we continued slagging ... (sic) That phrase keeps coming back to me all the time. "It's only me." It's become a mantra in my mind.”54

Here’s Paul telling the story in 1986—

“He was always a very warm guy, John. His bluff was all on the surface. He used to take his glasses down – those granny glasses – take ’em down and say, “It’s only me.” They were like a wall, you know? A shield. Those are the moments I treasure.”55

And again in 1990—

“No matter what’s happened, even though John’s dead, I don’t feel like we are ever gonna be apart. I think we’re a part of each other’s lives, we’re a part of each other’s karma, man! And, you know, there’s something kind of deeper than all the business troubles we went through. They were real enough! But… nah, I think through all of that stuff, there was always the John who would put down his glasses and he’d say: “It’s only me.” And that was it, I’d know what he meant! ‘Ya, it’s only Johnny! It’s only Lennon, he’s only having a laugh with us, it’s just a joke, really.’ There was always that feeling that at the bottom of things, no matter how bad it got — fights, sort of slagging matches, or anything — we still kinda liked each other.”56

Here’s Paul in 1991—

“I remember kind of arguing once about something musical or something, and I remember John kind of just taking his glasses down and saying: 'It’s only me.’ And putting them back up again.”57

And in Many Years From Now in 1997—

“John and I were arguing about something and I was getting fairly heated. John just pulled his glasses down his nose and looked over the top and said, "It's only me," and then put them back again. Just a moment. I think that was very symptomatic of our whole relationship: John would let the barrier down and you'd get a couple of moments of deep reality, then he was defensive again.”58

Here’s another 1997 interview—

“One of my great memories of John is from when we were having some argument. I was disagreeing and we were calling each other names. We let it settle for a second and then he lowered his glasses and he said: “It’s only me.” And then he put his glasses back on again. To me, that was John. Those were the moments when I actually saw him without the facade, the armour, which I loved as well, like anyone else. It was a beautiful suit of armour. But it was wonderful when he let the visor down and you’d just see the John Lennon that he was frightened to reveal to the world.”59

Paul tells the story twice in The Lyrics — once relative to “Here Today” —

‘But you were always there with a smile’ — that was very John. If you were arguing with him, and it got a bit tense, he’d just lower his specs and say, ‘It’s only me,’ then put them back up again, as if the specs were part of a completely different identity.”60

And in a grouchier form relative to “Silly Love Songs”—

“John always had a lot of that bluster, though. It was his shield against life. We’d have an argument about something, and he’d say something particularly caustic; then I’d be a bit wounded, and he’d pull down his glasses and peer at me and say, ‘It’s only me, Paul.’ That was John. ‘It’s only me.’ Oh, alright, you’ve just gone and blustered and that was somebody else, was it? It was his shield talking.”61

And one time in 2009, Paul told it differently—

"Whatever bad things John said about me, he would also slip his glasses down to the end of his nose and say, 'I love you'. That's really what I hold on to. That's what I believe. The rest is showing off."62

And here’s that verse of “No Words” again—

You want to turn your head away

But someone's thinking of you

I wish you'd see, it's only me,

I love you

Paul is a sophisticated lyricist, but understanding “No Words” doesn’t require any sophisticated lyrical analysis. First, the “All You Need Is Love” reference in the first verse, and then his “it’s only me, I love you” John story in the second verse. It’s a simple matter of matching the lyrics to the almost exact words of “All You Need Is Love" and the actual exact words in one of Paul’s most often repeated stories about John — the words that shortly after John’s death, Paul called his mantra.63

We very much need to stay in the realm of possibility rather than certainty, always allowing room for doubt. But in the case of “No Words,” I’m at a loss as to where to allow that room for doubt, because it’s difficult to find a credible way that Paul includes the lyrics of a “John song” and the words “It’s only me” in a song about not having the words to say “I love you,” unless it’s a song to John.

Only in this case, Paul’s reversing the story by taking down his own glasses of emotional reserve and reassuring a hurt and angry John that “it’s only me, I love you.” And maybe I’m just hearing a little of what I want to hear, but it seems to me there’s a very McCartney-esque sense of hope in Paul’s voice as he sings... that maybe, just maybe, it’s not too late to fix whatever went so very wrong between them.

This is, of course, just educated and, I hope, careful speculation. And I suppose a case could be made (albeit not a very good one) that in all of this — the “All You Need Is Love” quotation, the “it’s only me” story, the regret at not having said “I love you,” Paul is talking about platonic love, Or maybe he's just repurposing his memories of John to some hypothetical abstract female love interest who is not his wife with whom he’s having a difficult time expressing his love. All of that is, technically, possible — even though he’s said they were exclusively communicating in songs during this time period. And Paul would know that John would absolutely pick up on the “it’s only me” and “love is all you need” references.

But there’s the matter of the middle eight. Let’s back up and take a look—

Your burning love, sweet burning love

It's deep inside

You must not hide your burning love

Sweet burning love, your burning love

Obviously, this is yet another reference to hiding feelings. But it’s the “burning love” part that most demands attention, because this is an Elvis reference.

There are few lyrics more associated with Elvis than “Burning Love,” the title of Elvis’ last top ten single, released very close to the same time “No Words” was written.

If you know your Beatles history, you know that, like Paris is not just Paris in the world of John and Paul, Elvis is not just Elvis. Which is why there’s no reasonable way in which both Paul and John weren’t familiar with “Burning Love.”

Most people know Elvis’ music was a huge influence on both Paul and John, one of the handful of artists who first inspired them to pick up guitars, and we probably don’t need to document that again here. Paul called Elvis “the guru we’d been waiting for, the Messiah.”64 John told biographer Hunter Davies in 1968 that, “nothing really affected me until Elvis.”65

And it wasn’t just the music that inspired both John and Paul. They were taken by his looks as well. Journalist and friend Maureen Cleave once shared a story about John being “fixated on a photo of Elvis while repeating, “Isn’t he beautiful?”66 And Paul said in 1994, “I like him back around 1956, when he was young and gorgeous and had a twinkle in his eye, when he had a sense of humour, plus that great voice.”67

Paul goes on to tell the story—

“I remember being in school when I was a kid, and somebody had a picture in one of the musical papers of Elvis. It was an advert for Heartbreak Hotel. And I just loved it, and I just thought he’s just so good lookin’. He just looked...(sic) perfect.”68

And here’s Paul again in Anthology—

“In our imaginations back then, John was Buddy and I was Little Richard or Elvis. You’re always someone when you start.”69

Elvis was a huge influence for both of them. And when John talks about Elvis relative to The Beatles, he’s not just talking about Elvis. In an indirect way, he’s also talking about Paul.

In 1968, talking about the day he and Paul met at the church fete, John said — ”He was good, he was worth having. He looked like Elvis. I dug him.”70 And here’s John in 1966 — “We’ve got people who look like Elvis Presley too, in our camp, as well. So that he’s no trouble to us, you see.”71

Singer/songwriter Harry Nilsson recalls John telling him after the breakup that, “I fell for Paul’s looks, Harry, just like everyone else did.”72

And of course, 15-year-old Paul did indeed resemble a young Elvis, and not just in looks or charisma. In The Beatles’ black leather Cavern and Hamburg days, Paul was the “voice” of Elvis in the band, the one who covered Elvis songs because he could sound more like Elvis than John or George could.

And here’s a GIF of John writing “I love Elvis” over a picture of Paul during a taping of BBC’s Ready Steady Go in 196473—

Put all that together — plus a few more things we’ll get to eventually when we have more context — and it’s not hard to come up with John initially falling for Paul because he looked — and sounded — like Elvis. And of course that would be the case — how many of us have had the walking, talking, upside-guitar playing embodiment of our teenage idol (and maybe teenage crush) appear in front of us, and especially while we’re still teenagers?

It seems more-than-likely that for John, there was a strong association between Elvis and Paul. And it's pretty likely Paul knew this.

So now let’s go back to that whole “burning love” situation in the middle eight of “No Words.”

The song “Burning Love” is unambiguously erotic, and sung by Elvis, even more so. There is no reasonable way in which the phrase “burning love” in a love song sung by Elvis Presley references platonic love. In fact, one might even suggest that it’s another description of lifeforce erotic love, along with “love-fire-life” and “sex with wings.” And Paul almost certainly knew full well the implications of referencing “Burning Love” in a song to John.

Paul’s inclusion of a reference to Elvis, and an explicitly erotic one at that, in the middle eight — the section of a song that John more than anyone would know that Paul is especially gifted at composing — might be a signal to John that, yes, in case you had any remaining doubt, this song is for you.

There’s one more thing to notice about “No Words” before we wrap this up.

If you know your Wings history, you know that according to the credits on the album sleeve, “No Words” is a Paul McCartney/Denny Laine song — Denny Laine having been a guitarist in Paul’s post-Beatles band, Wings.

Denny has always claimed in interviews that “No Words” is his song. But beyond the small detail that Paul is credited as the primary songwriter, Denny’s actual story of the writing of “No Words” tells us that “No Words” is not, in fact, a Denny Laine song.

Denny has told the story of writing “No Words” with Paul many times, and he’s consistently vague about exactly which parts of “No Words” he wrote. And he’s consistent in acknowledging that he had only “bits” of an idea for a song, which he then brought to Paul to finish, but he never tells us what those “bits” were. On the other hand, Denny is specific that Paul contributed the “burning love” middle eight, and also that Paul wrote the final verse — that would be the verse that includes “it’s only me/I love you.”

Paul having written the “burning love” bridge and the “it’s only me/I love you” verse would be more than enough to make “No Words” what it is, relative to the lovers possibility. But there’s a bit more to tell about the origin story of “No Words.”

In his final interview shortly before his death, Denny was asked about Paul’s involvement with writing “No Words,” and he tells his usual story of bringing bits of the idea to Paul. He ends the story with, “It’s hard to keep [Paul] out of a song once he gets going.” And then it’s mentioned in the interview that Denny laughs.74

Maybe it’s just me, but “it’s hard to keep Paul out of a song once he gets going”— particularly given the laugh at the end of it — feels like it’s tinged with a touch of the amused resignation one might feel when their boss has taken over what used to be a personal project, which seems virtually certain to have happened because as Denny points out, Paul McCartney is Paul McCartney. And because Wings, after all, was first and foremost, Paul’s band. Denny was a salaried employee, not a full-fledged member or collaborator, however much he may have wanted to be and occasionally styled himself as being.

I suspect what happened here is that Denny brought Paul a vague idea for a song that bore a passing resemblance to some residual part of “No Words,” and by the end of the writing session, it was a Paul song about John — because this is the sort of thing that happens when you’re in a band with Paul McCartney and you’re not John Lennon.

“No Words” is the first song in which Paul explicitly, in so many words, tells John that he loves him. And maybe it’s a coincidence, but it’s not long after “No Words” that John and Paul reconcile and begin spending time together again, not long before John has planned to go to New Orleans to work on Paul’s new album with him.

And maybe it’s not related at all, since it’s just before the official release of Band on the Run, but in 1973, John had this to say about Paul’s music—

“I think we all had a little bit of pain75 from our divorce at that period and it was all rather painful to hear about it or listen to the music. But I think if you spoke to Paul now, you might hear a different story. Because, I mean, we’re just humans and we want changes, you know, some days, you like to hear stuff and some days you don't. But I think the story might be different now, just by his records.”76

Whether Paul sent John an advance copy of Band on the Run or not, John, it seems — regardless of what he was claiming in his interviews — was indeed listening to Paul’s “whispers through the wall.”

Interestingly enough, after “No Words,” Paul’s regret songs stop for a while. We don’t yet have enough context to talk about why that might be, but what matters here is that as with the emotional arc of their songs overall, Paul’s regret songs seem to follow the trajectory of his relationship with John — and only, it seems, his relationship with John.

A few traces of “I can’t express my feelings” songs in the ‘60s when they’re young and in love and living in each other’s back pockets, lots of “I wish I’d expressed my feelings” songs after the breakup, when he and John aren’t speaking, and then no regret songs following their reconciliation during the Lost Weekend — which, again, happens soon after “No Words” — and reappearing only after John’s murder, and continuing into the present day.

Unless Paul has another significant relationship that we don’t know about that lasted from the beginning of The Beatles through John’s murder, in exact parallel with Paul’s relationship with John, Paul’s relationship with John as reflected in his songs seems to be the only match for that pattern. For that emotional arc.

One of those post-1980 regret songs is “However Absurd,” from Paul’s 1986 album Press To Play.

We don't yet have anywhere close to enough context to do a thorough job of interpreting “However Absurd,” but any discussion of Paul’s regret songs would be incomplete without at least mentioning the bridge77—

Something sparks off between us

When we made love the game was over

I couldn't say the words

Words wouldn’t get my feelings through

So I keep talking to you

However absurd

However absurd it may seem

Obviously, “However Absurd” is an “I couldn't say I love you” regret song, and thus almost certainly a song about John, especially given that the verses fairly clearly tell the broad-strokes story of Lennon/McCartney.

It’s also a bit more than that, as you may have noticed.

Paul has written many regret songs since 1980, and many of them include fairly clear references to John. But “However Absurd” is singular, because it’s the song in which Paul most explicitly links erotic love to his relationship with John. The rest of “However Absurd” is written as absurdism — hence the title — but there is nothing absurdist about “when we made love the game was over.”

In 2015, Paul did an interview with Q magazine, in which he was asked the question about whether he worries about revealing too much of himself in his love songs. “Yes,” Paul answered. “but you’ve got to get over that feeling quickly, because that’s the game.”78

Of course, after 1980, there are no more whispers back through the wall from John. But If I can share a personal belief — and this is just a personal belief, not a mythological musing — I believe John hears Paul’s songs. And I think maybe, just maybe, Paul believes that, too, or perhaps he wouldn't write so intimately and so directly to John the way he does, still to this day — however absurd it may seem.

Until next time, peace, love and strawberry fields,

Faith

Paul McCartney, The Lyrics, Liveright, 2022.

In 1967, Italian film director Franco Zeferelli offered Paul the lead role in his film adaptation of Romeo and Juliet.

“Other than West Side Story, John hated musicals. West Side Story, we went to see together.” Paul McCartney, The Lyrics, Liveright, 2022.

The skit apparently left a lasting impression on Paul, because three years after that in 1967, he named a pair of kittens Pyramus and Thisbe. Beatles lore tells that Paul kept Thisbe — named after John’s part in the pantomime — and gifted Pyramus to John. It’s a lovely bit of lore, but I haven’t been able to confirm that Paul gave Pyramus to John. It seems at least possible, given John was a cat lover and Thisbe remains unaccounted for otherwise. If anyone is aware of any confirmation on this part of the story, please do let me know.

The full quote is “A man is least himself when he speaks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he'll tell you the truth" - Oscar Wilde, Picture of Dorian Gray.

Written by British music critic Ian MacDonald and published in 1994, Revolution in the Head is known for its strident embrace of the distorted breakup narrative, and for MacDonald’s scathing contempt for Paul’s role in the partnership and in the band. Paul is on record as protesting its inaccuracy — and correctly so.

“Q: I keep dipping into that Revolution In The Head book. Written, of course, by the late, great pop scholar and Uncut contributor lan MacDonald. A hugely compelling read by any yardstick.

PAUL: Well, it might be compelling reading for you. But not for me it isn’t. Because I keep finding all the mistakes in it. “McCartney did this because of that…” And I’m sitting there thinking, “No, I didn’t.” Or, “John Lennon was out of his head on this when he wrote that.” No, he wasn’t. I should know because I was fucking there. It’s all this received wisdom shit. It’s good that someone like lan bothered to write a book about us. I’m sure a lot of it is very perceptive. But what do you do when you’re me? When someone is telling you what it’s like to be in a room writing “A Day In The Life” and you’re thinking, “No, that’s not what it was like at all.” It can be very enraging, that sort of thing.”

Paul McCartney interview for UNCUT, “My Life In The Shadow Of The Beatles,” July 2004.