All the episodes of Beautiful Possibility in sequence are here.

You can probably read/listen to this without having read/listened to earlier episodes, but parts of it probably need episode 1:3 to fully make sense.

“The world is full of magic things patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper.” — William Butler Yeats

In a castle, the king lies bleeding.

Outside the gates, a solitary knight approaches the castle. His name is Percival, and he’s known far and wide as the bravest and most honourable knight in the realm. He’s weary, hungry and in need of shelter.

The gates are lowered and Percival is offered the hospitality of the castle. A page tends to his horses and directs him to the banquet hall, where the nobles of the court are feasting on rich food and wine.

As Percival joins the nobles at their feast, a beautiful young maiden enters the banquet hall bearing a Grail, pierced by a Lance.

Percival is curious about the meaning of this strange procession, but he’s been taught that a respectful traveller does not ask questions of his host, and so he says nothing and politely ignores the Grail, turning his attention back to the feast and the nobles at the table.

The next morning, he awakens to find the castle silent. The night prior it had been alive with activity, but this morning, there is no one about to speak to or even acknowledge his presence.

Confused, Percival makes his way to the courtyard, tends to his horse and departs. As he does, he hears a voice behind him. He turns to see a bent old woman shaking her head sadly.

“Foolish knight,” she says. “You had the power to heal the king and the kingdom, if only you’d asked about the Grail. Instead you chose silence. You’ve dishonoured yourself and your king.”

“But milady,” Percival protests, “I was but following the custom of the land, that a guest is to ask no uninvited questions of his host.” But the woman has already vanished. And when Percival turns back to look at the Grail Castle, it, too, is no longer there.

In its place is only the Wasteland.

For fifty years, mainstream Beatles writing, constrained largely by the customs and bigotries of a wounded culture, has failed to pay attention to the possibility that John and Paul were lovers. For fifty years, the Fisher King wound that could begin to be healed in earnest by that possibility bleeds steadily out onto the castle floor, as the kingdom sinks further and further into the Wasteland.

There are, of course, reasons for this failure to pay attention, just as there are reasons for Percival not to ask about the Grail. Most obviously, there’s the ethical concern that if Paul and John were a romantic as well as a creative couple, it’s their love story — and no one else’s — to tell or not tell, and until they choose to do so, no one else can or should tell it, either.1

If you’re uncomfortable talking about Paul and John as a romantic couple without first having talked through the ethics of talking about Paul and John as a romantic couple, I get that. I spent a lot of time being uncomfortable about it, too. And over the past three years of intense consideration of the ethical issues involved with writing the lovers possibility, I’ve come to understand that those ethical issues are not at all what they might appear to be at first glance.

And though it’s hard to see that now, everything we’re going to talk about between now and the end of part one of Beautiful Possibility is the context we need for dealing with those ethical questions the way they need to be considered. For now, I can only ask you to trust that we’re covering all of this material in exactly the order in which it needs to be covered, even though it might not seem like it.

In this episode, we’re going to consider the other major objection to the possibility that John and Paul were lovers — that it just isn’t credible, that there’s nothing in the research to support it, and that the whole thing is just the erotic fever dream of yet another generation of lovestruck females swept away by the Fabs and confusing fantasy with reality.

So, okay, obviously the back half of that objection needs dealing with, and we will for sure do that. But first, let’s turn our attention to the first part — that there’s nothing to the lover's possibility and no credible research to support it.

The problem with countering the credibility objection isn’t a lack of supporting research2 — quite the contrary. There's a significant — even overwhelming — amount of supporting research for the lovers possibility, and some of it is strong enough that it’s difficult to find an alternate explanation for it. There’s so much supporting research, in fact, that if this were literally any other topic, it would already be part of the mainstream story.

But of course the lovers possibility isn’t just any other topic, which is why most of the research supporting the lovers possibility never seems to find its way into any of those mainstream articles and books we’ve been talking about — even though much of that supporting research comes directly from John and Paul. And when that research does find its way into the mainstream story, it’s often skewed in such a way as to deflect away from the lovers possibility. Whether that skewing is conscious or not is anyone’s guess, but it’s hard not to wonder sometimes, when it becomes as heavy-handed as it often is.

We’ll look at a specific example of this skewing away from the lovers possibility in this week's Rabbit Hole, relative to Paul and John’s famous “Nerk Twins” adventure in Caversham in 1960.

For now, what matters is that all of this becomes a self-perpetuating cycle. Because the research that supports the lovers possibility has been distorted or omitted entirely from the mainstream narrative, it’s been my experience that many writers who rely on mainstream sources for their information aren’t even aware that this body of research exists — which is partly why so many of them so confidently dismiss the lovers possibility so definitively. Their assumption is that because it’s not in any of those “definitive” books, it must not be credible. This attitude is summed up by a comment I read a while back on a mainstream Beatles forum thread about the lovers possibility — “If there was anything to it, it would be part of the story already.”

Now is a good time to remind us that just as it would be illogical (and unethical) for me to declare for sure that the lovers possibility is true — because how could I know for sure? — it’s also illogical (and also unethical) for anyone who is not Paul or John to definitely declare that the lovers possibility is false — because how could they know for sure, unless they were glued to either Paul or John’s side every day and night from July 1957 through December of 1980?3

Before we move on to talking specifically about the credibility of the lovers possibility, there’s a caveat, and a big one — because one of the challenges here is that while there’s a substantial body of research to support it, most of the individual data points can be explained in some alternate non-lovers possibility way, if you’re motivated to do so and if you aren’t aware of the full scope of the research surrounding that data point.

So for example, I could tell you that in 1961, John and Paul took a trip to Paris, just the two of them, in honour of John’s twenty-first birthday. And while that might raise an eyebrow, you’d probably say, that’s interesting, but it doesn’t prove anything about the lovers possibility, and you’d be right about that.

Best friends do sometimes take trips together, just like Paul and George used to hitchhike places, just the two of them. Maybe John and Paul just wanted to go to Paris — you certainly don't have to be lovers to enjoy visiting the City of Love. And maybe John took Paul because John had never been out of the UK before and he didn’t want to go on his own and he couldn't take his then-girlfriend Cynthia because in 1961, no respectable middle-class Liverpool parent would let their young, unmarried daughter go to Paris alone with her boyfriend — especially if her boyfriend is John Lennon.

All those things are valid, and if you’re looking for a reason to discredit the lovers possibility, it’s easy to look at the Paris trip in isolation and simply choose the alternative explanation.

But individual data points can’t be considered in isolation, when they’re part of a larger story. And when we put the Paris trip in its full context, we get a very different picture.

When you also know that it wasn’t a mutual decision, but rather John inviting Paul to come with him to Paris, and that John paid for almost everything, and that they stayed there together for almost two weeks, just the two of them, in a little hotel in Montmartre—

—And when you know that John and Paul returned to Paris in 1964 on The Beatles’ first international tour at the beginning of global Beatlemania, and that they stayed in a luxury suite at the George V Hotel, which is as posh as it sounds, and that it was there that, in beautiful synchronicity, they learned that “I Want To Hold Your Hand” — a song about a longing to hold hands, presumably in public — had reached number one in the US, meaning they’d made it to the toppermost of the poppermost together, and that multiple people who were on tour with them, including George Harrison, have written about how John and Paul spent an unusual amount of time alone in their suite in Paris to the point that it became a problem,4 and that staying in that posh hotel, Paul to this day recalls thinking of their first Paris trip, staying in a cheap hotel with only a hundred pounds in their pocket.5 And when you know that when they at last emerged from their self-imposed seclusion in their posh 1964 hotel suite, they’d written the song “Can’t Buy Me Love”6 —

And when you know that a decade later, Linda McCartney asked John if he missed living in the UK, and John’s answer was, “I miss Paris,”7 and in a separate interview, said he loved Paris because of how people could be so openly affectionate and romantic, kissing and holding hands in public, and when you know that same-sex love was legal in France in 1961, so two boys could hold hands and kiss and show affection in public the way, if they possibly wanted to, they couldn't in England8—

And when you know that in the ‘70s, John wrote a story about his memories of meeting his lover in Paris for a secret rendezvous9 and that there’s a home recording of John in the late ‘70s singing a parody of an old French love song in which he calls Paul’s name and riffs about his romantic memories of Paris and a “cafe on the Left Bank,”10 and when you know that in 1978 Paul wrote and recorded a song titled “Cafe on the Left Bank” inspired by their trip11 —

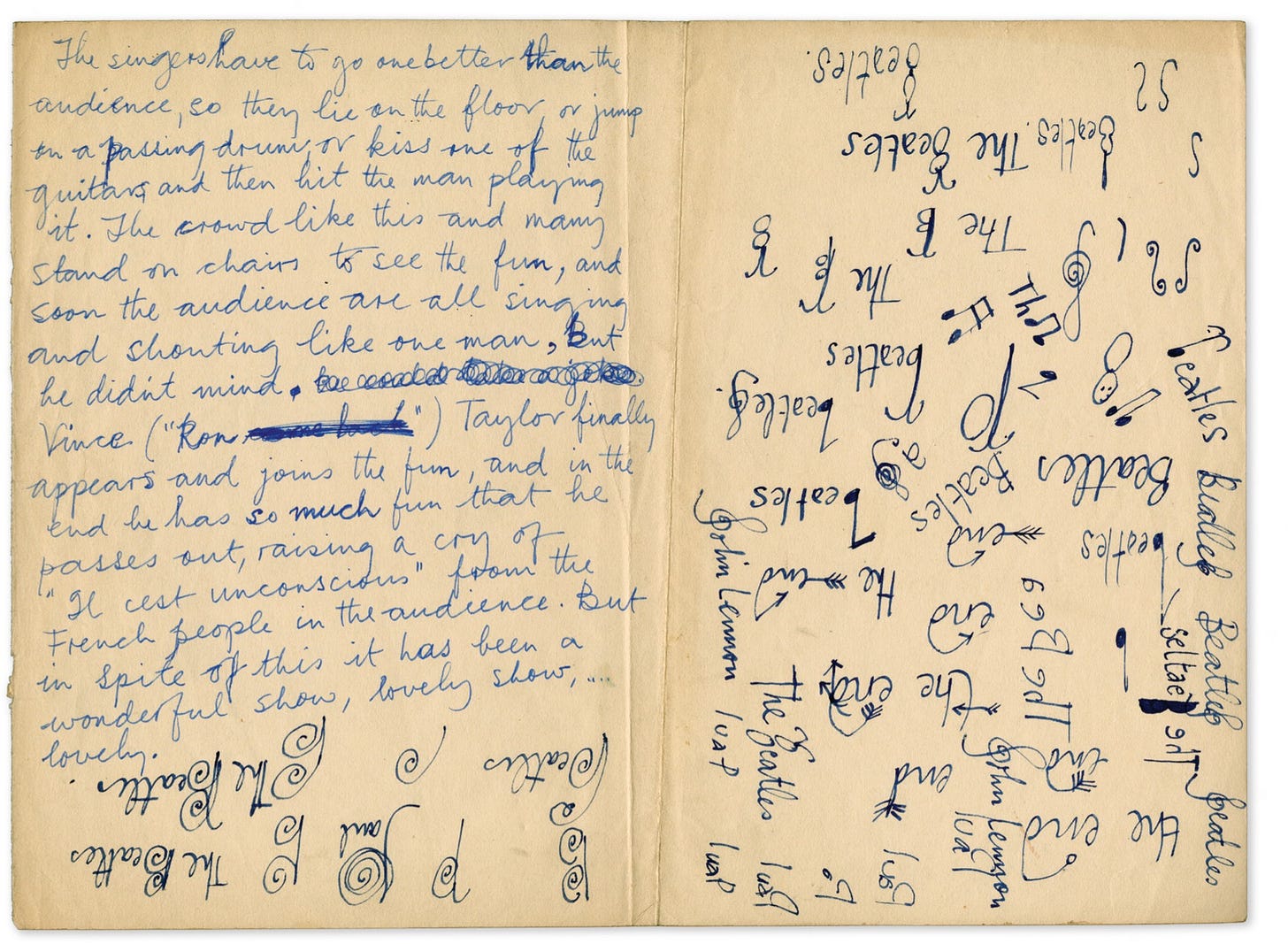

And when you know that the diary page Paul chose to feature in his Lyrics book and in his Eyes of the Storm exhibition (and I do mean featured, as in displayed in the centre of the room in a glass case) is from that original 1961 Paris trip, on which he and John wrote their names together in various configurations exactly like two teenagers in love,12 and that in 2007, Paul was interviewed on French television and asked what his idea of heaven was, and his answer was his trip with John to Paris in 196113 —

When you know all of that, the Paris trip starts to take on a different context.

Mainstream Beatles writing doesn't put those pieces together though — if they even know this research exists. Instead, writers just mention that John and Paul met up with a friend from Hamburg in Paris and that he gave them what became the Beatles haircut — relevant information, to be sure, but it rather misses the larger point.

Whatever else happened between them in Paris, their first trip there together is clearly a significant and cherished part of their relationship story for both of them, and I don’t think it's because they got their hair cut.

When a shared experience becomes deeply emotionally significant in a relationship, it becomes a shorthand for everything that experience represents about that relationship. And when it then appears in other contexts relative to their history, it carries all of that meaning along with it.

The most iconic example of this, of course, is from Casablanca. In the famous final scene at the airport, Humphrey Bogart’s character tells Ingrid Bergman’s character as she’s about to get on the plane with her husband that, “We'll always have Paris. We didn't have... we lost it until you came to Casablanca. We got it back last night.”

When he says “Paris,” Bogart isn’t talking about the city, not directly. He’s referencing their shared emotional experience and memories of Paris — what Paris means to their love affair — and he shorthands all of that to just the name of the city where that experience happened and where those memories were made. And because the experience is so significant to both of them, she instantly knows what he means — and so does the audience.

Paul and John seem to reference Paris in the same way as Bogie and Bergman do in Casablanca.

Just like in Casablanca, Paris is never just Paris when it appears in this story relative to John and Paul — and without understanding that, we miss the significance of those references and what they might tell us about the story, as well as the music that was being written at the same time.

For example, events like John “honeymooning down by the Seine” with Yoko in 1969, as he wrote in “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” and then asking Paul to help him record the song, become far more emotionally complex when we know that Paris is always more than just Paris between the two of them.

Without understanding the collection of experiences and emotional associations that’s referenced every time Paris appears in the story relative to John and Paul, I don’t think it’s possible to understand the meaning of that trip, or the meaning of “Can’t Buy Me Love” or “Ballad of John and Yoko,” or John taking Yoko to Paris,14 or John’s feelings about living in New York, or a host of other significant parts of the story. Without an awareness of the lovers possibility, the fuller context and meaning of those events remains invisible, and out of reach.

And without being sensitive to romantic and emotional subtext, you can’t put those pieces together. Paris becomes just a story about a haircut.

I’ve occasionally heard people protest that the problem with the lovers possibility is that it makes a complex relationship too simple. Putting aside that this isn’t in and of itself a reason to discount it — just because we don’t like what something does to a story doesn’t mean it’s not true — the Paris trip is an example of how it’s the other way around. It’s by stripping the lovers possibility out of the story that we oversimplify it — and miss the more beautiful story.

When we focus only on individual pieces of information without doing the work of putting together the whole puzzle in its broader context, we miss the bigger, more complete and complex — and more beautiful story. And this is why it’s difficult to present supporting research for the lovers possibility, because most of that research requires context to be fully understood.

This is true in any field of study, not just relative to The Beatles or the lovers possibility.

Pioneering Grail scholar Jessie L. Weston called this focus on individual details at the expense of the larger context “criticism by isolation,” and she warns that “so long as critics of the story” — and here she means the Grail story, but it’s just as true of the story of The Beatles — “will insist on pulling it into little pieces, selecting one detail here, another there, for study and elucidation, so long will the ensemble result be chaotic and unsatisfactory.”15

“Chaotic and unsatisfactory” is about as good a definition of the current state of the Beatles’ story as I can think of, mostly as the result of writers contorting themselves into Lennon-esque pretzels to avoid including evidence of the lovers possibility in all those “definitive” books — for reasons we’re about to get to.

Overall, though, it’s the significant body of supporting research taken as a whole and the larger context in which it sits that begins to establish the credibility of the lovers possibility. The best answer to “is it credible that John and Paul were lovers?” might be that it resolves virtually all the blank spots and inconsistencies in the overall story — and that it seems to be the only thing that does.

Again, this isn’t some new way of thinking about all of this that I’ve invented to support my thesis. Cambridge professor of classical studies Frances Concord pointed this out all the way back in 1934, when he suggested that “the true test of an hypothesis, if it cannot be shown to conflict with known truths, is the number of facts that it correlates, and explains.”16 Meaning that the credibility of a theory rests on how well it resolves the parts of the story that are nonsensical or unexplained. Which is exactly what the lovers possibility does — as we’ll see when we re-tell the story through the frame of the lovers possibility in the second part of this series.

There is a short list of individual pieces of research that by themselves seem to have no credible explanation other than the lovers possibility, and I’ll share those with you as we progress through this series — although I won’t identify them as such, so you can draw your own conclusions. But even these individual pieces of research require fuller context to understand why they’re so convincing.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. For now, let’s deal with the second part of the credibility objection — you’re just swept up in a romantic fantasy, seeing what you want to see because you think the idea of John and Paul together is hot. Translation: Those of us who advance the lovers possibility can’t be taken seriously because we’re thinking with our hearts... and y’know, other lady parts... and not our heads.

My dear reader, can you hear my sigh of frustration here? There are so many problems with this line of what we’ll politely call reasoning that I’d need charts to step through them all. You might have already noticed the most obvious one—

Since most — though by no means all — Beatles scholars who pay attention to the lovers possibility are female, “you’re seeing what you want to see because you think it's hot” is essentially a rehash of the tired old trope that women are too emotional and too carried away by our romance novel fantasies and out-of-control libidos to be able to think rationally about important things, so step back, little lady, and let those of us who are capable of keeping our emotions in check — which usually means the men in the room — handle the serious work of studying Lennon/McCartney.

Well, first and foremost — and please forgive me if I get a bit overly technical here, but — fuck exactly and precisely all of that nonsense.

Except...

As with almost everything that seems straightforward about this story, the “you just think it’s hot” objection is more complex than simple sexism, although it is certainly also that. The accusation that those of us who think John and Paul might have been lovers are swept away by the romance of it is undeniably sexist — but it’s also... true.

In case you hadn’t noticed already, yes, I’m completely, incurably swept away by the possibility of a love affair between John and Paul. The thought of these two beautiful, brilliant men passionately in love and in each other’s arms is take-my-breath-away romantic and gorgeous and, yes, hot as hell, and for this reason alone, I want it to be true. And more than that, as I shared in the prior episode, for me and for many others, the possibility that John and Paul were lovers makes the world a more beautiful and hopeful place, and my ecstatic, transformative experience in discovering this possibility was the initial inspiration for this series.

Because the internet has no secrets, I’ll also tell you that in addition to my “aboveground” writing on The Abbey, I write and read John/Paul slash fiction17 and I make absolutely no apologies for that. While it has its own ethical complexities, speculative fiction, erotic or otherwise, about real people can be an invaluable tool for understanding at a deeper level the relationships between historical figures. The insights gained as a result of reading and writing John/Paul slash fic have significantly enriched my thinking on not just the lovers possibility, but on the story of The Beatles overall and in my broader work as a predictive mythologist. Maybe we’ll talk more about all of that some other time, but for now—

The wonky term for this emotional attachment to a theory is, as you might know, “confirmation bias” — meaning that we tend to see what we expect and/or want to see rather than what’s really there. And yes, as a professional who’s been doing this sort of work for awhile now, I’m well aware that confirmation bias distorts thinking if it’s not consciously adjusted for. Being aware of and acknowledging that bias is a big part of consciously adjusting for it, so consider it acknowledged.

As for the rest of it, that’s where the “you’re just swept away” objection comes in — because when it comes to questioning the credibility of the lovers possibility, the whole problem might lie not in being too swept away to think clearly, but in too many mainstream Beatles writers not being swept away enough.

A colleague of mine, a long-time mainstream Beatles writer, once confessed to me that he has trouble getting his head around the lovers possibility because he “doesn’t speak the language” necessary to notice and respond to that possibility. And more than that, he dreads the day the lovers possibility becomes part of the mainstream story, because he’s afraid the “hardness” of the story will be lost.

This same colleague was literally the first person to encourage me to write this series, despite his personal misgivings, and I’m appreciative of his support. But I can’t help but ache that he feels the possibility of John and Paul as lovers somehow diminishes the story of The Beatles. It's a sad case to make, that any story would be made less beautiful by the addition of a passionate love affair. Even sadder is that he’s not the only one who feels this way. And sadder still is that, in my experience, most of the people who don’t want the lovers possibility to be part of the story are — not surprisingly — men, most of them of the same generation as the writers of all of those mainstream Beatles books.

It’s tempting to simply label my colleague’s point of view as homophobia and move on, as many people in the Beatles countercultural studies world do, and that’s not an unreasonable accusation. The overwhelming majority of mainstream Beatles writers have been and continue to be men who came of age during a time when the larger culture explicitly taught that love and sex between men is wrong wrong wrong.18

It’s not a big shock that many writers who grew up in the explicitly homophobic culture of prior generations would be resistant to any suggestion of a romantic relationship between John and Paul, even if they recognised it when they saw it — which they probably wouldn’t because as my colleague pointed out, they don’t “speak the language” necessary to recognise it. And regardless of how much information there is to support something, you’re not going to see it if that information is in a language you don’t understand.

But I think labelling the refusal to pay attention to the lovers possibility as “just” homophobia is less than helpful, and also perhaps less than fair.

Yes, many of these (mostly though not always male) Beatles writers have a blind spot when it comes to the intimacy of the relationship between John and Paul, even without the lovers possibility. And most of them seem unable to connect with the beauty of that possibility, even if they've acknowledged that it’s credible. These are, after all, the same writers who believed and perpetuated John’s distorted breakup narrative despite the abundance of evidence to the contrary.

But these first generations of Beatles writers are also the children of the Sixties and the children of the children of the Sixties. And while the Love Revolution outside of artistic circles wasn’t always especially enlightened when it came to same sex love, its overall arc did bend towards social justice. And that worldview was passed on as a cultural inheritance to future generations, including people who write about The Beatles.

So I feel very safe in saying that most of the same writers who deny and sometimes ridicule the possibility of John and Paul as lovers, and who fail to see its credibility and its beauty, are in general opposed to prejudice of any kind and would be genuinely distressed to be accused otherwise.

In other words, while it’s always dangerous to generalise 😎, I think it’s a fair generalisation to say that not being a bigot tends to go hand-in-hand with writing about the Fabs.

Still, it’s different, when it’s personal. Rational thought and evolved social consciousness are no match for the monster under the bed. And here’s where we arrive, finally, at fear.

Before we go further, I’ll say in advance that men in particular haven’t always reacted well when I’ve shared, well, the whole rest of this series, actually — but especially this next part. The thing is, though, I can’t make it less true than it is.

It’s easy to forget that the word “homo-phobia” translates to fear of same sex love. It’s a unique prejudice in our culture, word-wise — the only prejudice explicitly labelled as fear, though of course prejudice is the usual reaction to fear. And the thing about fear is that it doesn’t give a toss about our abstract political beliefs or moral principles. Fear — like love — has a mind entirely of its own — a thought that’s maybe some comfort for where we’re about to go with all of this.

This fear seems to be most acute for men who identify most strongly with John and who formed that identification in their teen and young adult years — which seems to be almost universally true of especially those earliest generations of Beatles writers, like Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner, whom we talked about in the prior episode. And of course, because they identify primarily with John, they have a heightened confirmation bias towards his version of events, rather than Paul’s — and we’ll come back to why in a future episode.

For a man who came of age in Western culture in any era, and especially before the cultural shift in attitudes towards same sex love, the possibility that a role model — an idol — around whom their self-identity has been formed, might have had (or even wanted to have) a romantic and sexual affair with his male songwriting partner (or for that matter, the male manager of his band or his male art school roommate) is almost sure to stir up whatever homophobia might be lurking in the secret depths of his psyche, even if that homophobia — that fear — isn’t consistent with his beliefs or values, and even if he knows, rationally, that it's a false and hurtful fear.

And that fear leads us back to the legend of the Grail.

The men don’t know what the little girls understand. — Willie Dixon19

The search for the Grail is Western civilization’s most iconic quest — and also maybe its most puzzling and least understood — because the Grail legends were essentially the superhero franchise of the Middle Ages, but there’s really no superhero-ing going on in them.

There are no battles to fight, no significant tests of physical strength or skill, no duels or jousts or dragons to slay. Instead, the Grail Quest pretty much consists of wandering around for years lost in the Wasteland, arriving at a nicely-kept castle, being welcomed with good food and wine (and depending on the version of the story, other delights) and noticing and asking about — or in most cases, failing to notice and ask about — a cup (penetrated by a lance) that’s carried through the banquet hall.

That’s it. That’s the big, iconic quest of Western civilization.

Very strange.

It’s even stranger that despite the near-complete absence of physical danger, the Grail Quest is undertaken by only the most courageous knights of the realm. And it’s stranger still that most of those otherwise-courageous knights fail the test.

We can only be very brave if we’re very afraid, so what is it about the Grail that makes it so terrifying that only the bravest knights are willing to search for it? And what’s so difficult about asking after a cup that makes even the bravest knights fail in their quest? I mean, how hard could this possibly be?

The answer to these questions will eventually lead us to the credibility of the lovers possibility.

It starts with noticing that, despite the equal presence of the Lance in the story, the quest is only for the Grail. Not noticing the Lance might be an oversight on the part of after-the-fact Grail scholars, but I don’t think it’s an oversight on the part of the original Grail writers.

As we talked about in the prior episode, given the distinctive shape of the objects involved, the Grail story is an allegory of sexual lifeforce healing. And obviously, in the symbolic sex act being enacted, the Lance is intended to represent the masculine, while the Grail represents the feminine.20

Mythological stories are profound but not perfect. And here we arrive at what seems to be a design flaw in the legend of the Grail, when it comes to healing a wounded culture — the segregating of essential qualities of being a complete human into “masculine” and “feminine” based on biology and anatomy.

We all know this already, but let’s say it anyway— for millennia, Western culture has drawn a sharp line between what’s considered “masculine” and what’s considered “feminine,” and punished anyone who dares to step over that line.

As we talked about in the extended Rabbit Hole on Beatlemania, a woman is allowed to be — or depending on your point of view, expected to be — fluent in the language of emotion. And at least when we're young, allowed to be openly swept away by passion and romance.

But a man risks his masculinity if he does anything the culture thinks of as “for girls only” — if he shows too much emotion or allows himself to be swept away by love or passion. Even in bed, a “real man” is expected to perform, to be in control, always, and not to surrender to ecstasy or allow himself to be "made love to.” A "real man” isn't supposed to be moved to tears by pain or grief or beauty, or show tenderness or sensitivity to, well, anything really.

Again, we know this already, but let’s put it in the context of the Grail legend.

A more accurate description of the lifeforce power of the Grail is what we might call receptivity — an ability to open ourselves to the lifeforce love, created by the union of the Lance and the Grail — so it can work its ecstatic, transformative magick.

Receptivity is too sterile a word to apply to magick, though. A better word — though not a perfect one — might be softness, to contrast with the hardness of the Lance. But when I say “softness,” I don’t just mean soft like a pillow, although that can certainly be part of it. I mean the kind of softness that allows us to feel emotions, including love and passion.

The Grail represents our willingness to open ourselves, to soften — not in a passive, or in any way weak, sense, but rather in allowing ourselves to be swept away by passion and love and erotic desire.

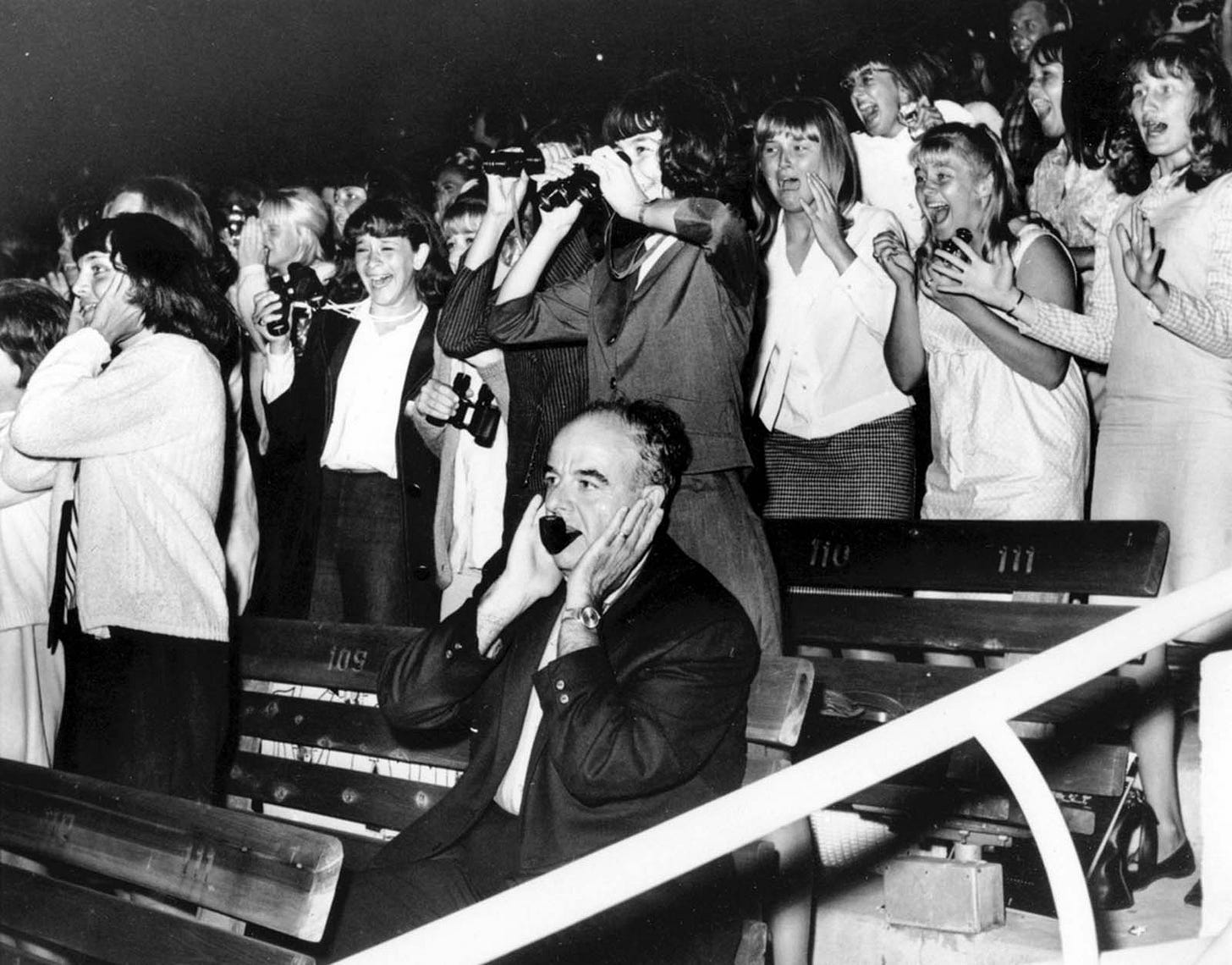

Without this softness, this receptivity, we can be in the midst of a tsunami of lifeforce love — say, for example, a Beatles concert — and be unable to recognize that love, much less let it in. These are the people you see in the film footage of those concerts who are looking around, mystified, at what’s happening, or putting their hands over their ears.

Without receptivity, we look at the Paris trip and think it’s a story about getting a haircut.

Men in Western culture are taught that this receptivity to emotion and passion is emasculating, that it’s an either/or situation.

A man can be sensitive and receptive to emotion — qualities traditionally associated with the feminine — or he can be a “real man,” hard and rational and not open to emotion — which is why so-called “real men,” like those battle-tested knights who seek the Grail, often feel the need to go through life in a metaphorical suit of armour, to make absolutely sure none of those softer, aka “feminine” qualities, can get in... or out.

It’s worth taking a minute to remember how ancient and deeply embedded this association is, between being soft — aka receptive to emotion — and being less than a man. It goes back at least as far as classical Greece, where the same words that meant “soft” — leios and malthakos — were used to describe a man who was weak and therefore unmanly, and not coincidentally, effeminate.21

It’s this association between softness and femininity that makes the Grail Quest so dangerous for a man in Western culture. It’s also this association between softness and femininity that keeps many men (and some women) from being willing or able to see the credibility of the lovers possibility — which is why just labeling it homophobia is oversimplified.

What might be more truthfully going on here isn’t homophobia per se — it’s Grail phobia. Fear of softness. Fear of emotion.

Fear of softness isn’t just about a fear of pillow-softness. It’s also about the fear of this receptivity, this openness — a fear of losing emotional control, of being swept away, of becoming one of those “hysterical’ Beatlemania teenagers.

This fear of softness is why for many men, living with the pain of John’s angry, hard version of the story — toxic as it may be — likely feels less traumatic than acknowledging the possibility that, at the heart of the story and the music that has shaped our culture and their sense of self, is a deeply intimate, deeply loving, deeply romantic erotic relationship.22 It’s also the beginnings of understanding why Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner was so determined to publish John’s distorted breakup interviews — in spite of John’s requests not to — that he was willing to sacrifice his own moral compass and his friendship with John to protect it.

Obviously there’s an extra layer of fear if that love affair is between two men, but the base fear — the fear of softness — would probably be there even if at the centre of the story of The Beatles was a love affair between a man and a woman, because men in Western culture aren’t supposed to respond to love stories at all, regardless of who’s pairing up with who. And that fear — my friend’s fear about losing the hardness of the story — is a fear that if the story of The Beatles turns into a love story, they won’t be able to tap into its superpower anymore.

This fear of softness is ancient and deep and powerful. For thousands of years, this fear has been leveraged by the powers-that-be to keep men from the Grail. Because as those same powers-that-be discovered in the Sixties, if men embrace the lifeforce love of the Grail, it’s a lot harder to get them to go to war — literally or in the corporate trenches — in defense of “suffer now, rewards later” and “might makes right.” And of course, this is a really big deal, given the history of Western civilization is largely a history of war.

One of the ways this fear of softness shows itself most obviously is the difference in the reaction when I share the lovers possibility with men versus with women.

Men almost always immediately characterize the lovers possibility as either accidental or circumstantial (“It was the Sixties,” “there were lots of drugs”) or as transactional and meaningless, describing it in crude and impersonal terms more suited to a porn video than a love affair. That crude characterization often has an aggressive quality to it — as if the (possible) intimacy involved was an assault or an attack, rather than a loving embrace. It seems likely this is an instinctive protective mechanism — a sort of an emergency retro-fitting of the new information into the story without having to acknowledge the softness of the Grail.

And while some men do immediately see that it explains things like the savagery of the breakup, they tend to react in a more intellectual way — as in, “oh, right, that makes sense.” Thinking, not feeling.

Conversely, when I talk with women, they tend to connect immediately with the romance of the lovers possibility. Their eyes light up and there’s often a little gasp of discovery and delight. Many women also immediately recognise how it explains the savagery of the breakup, but when women say, “Oh! That explains so much,” there’s a delight there — an emotional reaction. Women tend to feel how it makes the story make sense, rather than just thinking it. They experience the lovers possibility as a deeper articulation of the bond between John and Paul — and bond that they already intuitively sensed was there.

It’s important to emphasise that while these reactions mostly fall along gender lines, they don’t completely — we’re all unique even as our cultural conditioning is the same. Several of the men who have been most supportive of Beautiful Possibility are deeply connected to the lifeforce love at the heart of it. And several women I’ve met who’ve been… less supportive continue to frame anything that might have happened romantically between John and Paul as ”it was the Sixties and there were a lot of drugs.”

I’m tempted to say the difference between these two reactions is the difference between the Lance and the Grail, and in a sense, it is. But really, it’s the difference between fear of the Grail and the Grail itself.

The obvious problem here is that none of this “masculine/hard” vs “feminine/soft” business is actually true, and that’s the tragic flaw in the Grail legend. History follows mythology, and by making the Grail “female,” we’ve put softness, a fundamental part of being a whole person, out of reach of men.23

None of the qualities of the Grail or the Lance are by definition “masculine” or “feminine,” it’s only the culture that’s made it so. But tragically, the culture has made it so, and this is the fear that surrounds the Grail.

To put it bluntly, if Percival asks about the Grail, he’s afraid he’ll turn into a girlie man. And translated into our situation, that means a lot of men who write about The Beatles are afraid that allowing the lovers possibility into the story — even just as a possibility — will turn them into girly-men. And unfortunately, while we’ve made some progress, Western culture is still very much not okay with that.

But of course, the legend of the Grail shows us that it’s exactly the other way around. The Fisher King is emasculated by his groin wound not because he opened himself up to the softness of the Grail, but because he hasn’t yet found the courage to do so.

A man who acknowledges the Grail won't be unmanned — quite the opposite. By paying attention to the Grail, the Fisher King heals his wound (is it clear by now that Percival is also the Fisher King?), and becomes not less of a man, but rather a whole man, and his kingdom becomes a whole culture.

As with most things in this story (and in life), the choice between the Lance and the Grail isn’t either/or, it's both/and. A man’s reward for his courage in defying our wounded either/or culture by acknowledging the Grail is to possess the power of both the Lance and the Grail, to become not less, but more of what a man truly is — because the qualities of both the Lance and the Grail are essential for becoming a whole, healthy human being, regardless of biology or gender.

Not by accident, the knight who successfully completes the Grail quest becomes a king.

So now let’s go back to the objection that those of us who see the possibility that John and Paul were a romantic couple are too swept away by the romance and eroticism of it to be capable of seeing and thinking clearly, and to my friend’s admission that he “doesn’t speak the language” required to see the credibility of the lovers possibility, or to understand why it matters.

I hope you might be starting to see that the truer truth hiding in the “you’re just swept away” objection is that fluency in the language of softness and of emotion — the language of the Grail — isn’t a liability for recognising the credibility of the lovers possibility, it’s a requirement.

Confirmation bias makes people see what they want to see, but it also works the other way around — it also blinds us to what we don't want to see.

Fear of softness — aka fear of the Grail — is almost certainly the root cause of the willful blindness that leads those (again, mostly male) writers to ignore and ridicule the lovers possibility as nothing more than a romantic fantasy — thus justifying omitting most of the research in support of it from the story. And more than that, consciously or subconsciously writing the story to exclude the chance of anyone else seeing it — and I’ll show you a specific example of that in this week’s Rabbit Hole.

Sadly, this isn’t a conspiracy, which would at least be a little sexy and fun. It’s just garden-variety fear. And it starts to get us to the deeper reason why those first generations of journalists so easily believed John's distorted, angry, hard breakup narrative — even though it went counter to everything they’d seen — and felt — for themselves over the entire decade of the 60s.

What my friend who doesn't "speak the language” necessary to recognize the lover's possibility in the story is saying — and he might not be my friend after this episode, but again, I can’t make the following less true than it is — is that he doesn’t speak the language of the Grail. And more than that, he’s not willing to undertake the Grail quest that would teach him how to speak that language, and that he’d prefer to continue to ignore the Grail and to live with a bleeding groin wound rather than risk losing the power of the Lance. That’s all understandable, but no less heartbreaking for being understandable. Most knights fail the Grail quest, after all. Most knights never even attempt it in the first place.

The problem is, having an opinion about the credibility of the lovers possibility when you don’t speak the language of the Grail is like having an opinion about the plot of a novel written only in French when you don’t speak French. It says more about the person having the opinion than it does about the novel. In other words, dear reader, it seems the Beatles writers who dismiss the lovers possibility out of hand have more or less literally lost the plot.

All of that said, my friend isn’t wrong in experiencing the story of The Beatles as a hard story.

From their early days black leather “fuck you” defiance of social norms to Paul screaming “Long Tall Sally” into the firmament at Shea, to the savagery of the breakup and a thousand other moments in between, hardness is the edge that we sense in their music, part of what makes them The Beatles and not the Beach Boys.

That hardness, — that aggression and ambition — is another, equally important, aspect of the magick of The Beatles’ mythological earthquake-causing cultural power. Leading a world-changing revolution doesn’t happen with only the soft power of the Grail.

But my friend is wrong to try to force the story of The Beatles to be only a hard story, just as it would be wrong to force it to be only a soft story.

The Beatles took the hardness of early rock-and-roll and R&B and married it to the softness of music hall, Tin Pan Alley, and the exuberant passion of Tamla/Motown and Decca girl groups. They married the hardness of black leather to the softness of long hair and tailored suits. They married the hard post-war working class sensibility of Liverpool and early American rock-and-roll to the filthy decadence of Hamburg, and then made it a ménage à quatre by marrying all three to the soft artistic sensibility of Parisian bohemia and the avant garde.

It’s not either/or. We don’t have to give up the hardness, the edge, the aggression, to acknowledge the lifeforce love at the heart of this story. We don’t have to lose the Lance to find the Grail — they’re conjoined, a pair of intertwined lovers, each incomplete without the other, just as Lennon is incomplete without McCartney, and just as the two of them are incomplete without George and Ringo. Because the world is round, it turns us on.

The legend of the Grail asks the Grail Knight to pay attention to the Grail not because the Lance doesn’t matter, but because he already has the Lance. The search for the Grail is because the Lance really doesn’t need any additional attention in Western civilization. With the exception of the Sixties, it’s been more or less nothing-but-Lance for more than two thousand years.

I want to be really, really clear that in no way am I suggesting only women are qualified to write about The Beatles or to consider the possibility of John and Paul as lovers. That would be as ridiculous as saying only women can be soft and only men can be hard. That sort of rigidly dualistic thinking is what got us into this mess in the first place — and I’m talking now not just about the problems with the story of The Beatles, but the problems with more or less everything.

I also want to be really clear that in no way am I suggesting that all male Beatles writers are reluctant to include the lovers possibility in the story. Again, several of my most supportive colleagues in doing this work are men who see the credibility of this possibility, and its importance to the story as a source of lifeforce love. And again, I know a few female Beatles writers who are adamant that the lovers possibility is a fiction — and more sadly, don’t understand why it matters that it be included in the story.

But what I am suggesting is that because of what our culture teaches men about masculinity, it’s almost by definition more likely to be men who are uncomfortable with the possibility of John and Paul as a romantic couple, and in my experience, this does overall seem to be the case.

And this matters —- because the vast majority of people who write about The Beatles, even today, are men.

You don’t have to think John and Paul together is hot to see the evidence of the lovers possibility, but it certainly helps not to be terrified by it. Women and girls are more likely to notice the lovers possibility and to understand why it’s important because the culture hasn't taught us to be terrified by it. We’re allowed to speak the language of the Grail, whereas most men are not — or at least fear that they are not. It shouldn’t be that way, but this is the reality of how things currently are.

Fluency in the language of softness — the language of the Grail — is a requirement for recognising the signs of a secret love affair, and especially a secret love affair that challenges the narrow definition of masculinity imposed by the culture. An affair that — if there is truth to the lovers possibility — was intended to be concealed from anyone who doesn’t speak that language during a time when same sex love was illegal and unacceptable in the mainstream culture The Beatles’ music was reaching.

We’ll pick this thread back up again in a few episodes, when we’ll take a closer look at the more complex, more complete masculinity that The Beatles and the Love Revolution offered — and continue to offer, if we as a culture choose to pay attention.

With all of this in mind then, let’s look at how seeing the relationship between John and Paul through the soft gaze of the Grail can establish the credibility of the lovers possibility without having to reach for hard “proof” — just by looking at what we already see with open eyes, an open mind, and a softer, more emotionally receptive perspective.

We’re going to start on that by using what’s called a priori reasoning — reasoning that comes from looking at what we already know about the story using basic reasoning and common sense, and also in this case, a softer gaze — less the soft gaze of mythology, and more the even softer gaze of the human heart.

Again, I realise that talking about this before we’ve talked about the ethics of talking about this is pushing limits, but again, regardless of what you mght feel absolutely sure is the case, the ethical questions here are much more complicated than what they might seem, and to deal with them appropriately, we first need to establish the credibility of the lovers possibility. We really are doing all of this in the exact order in which it needs to be done — even if it might not seem so. I can only ask you to hang in there with me, and all will be clear eventually.

“There is an unmistakable look that two people have when they are in love. You can’t manufacture it. And if you’re experiencing it, you can’t hide it.”24 — Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love

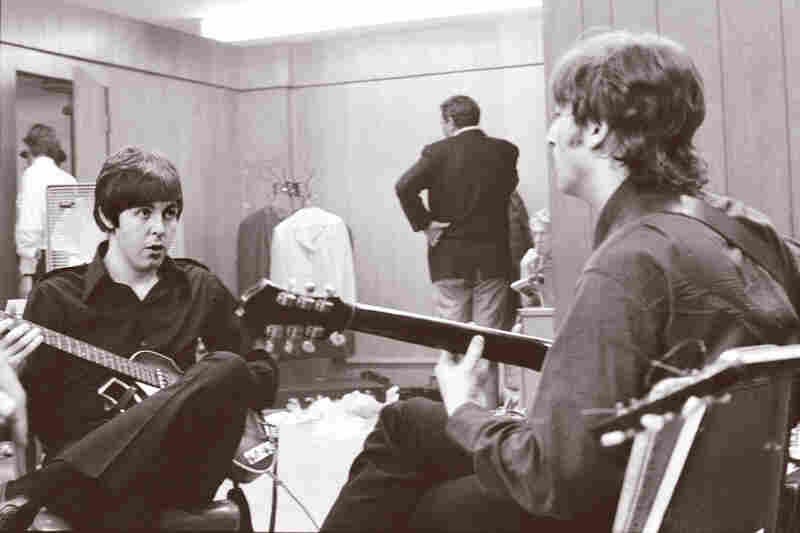

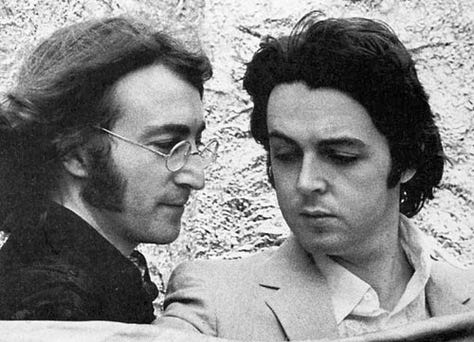

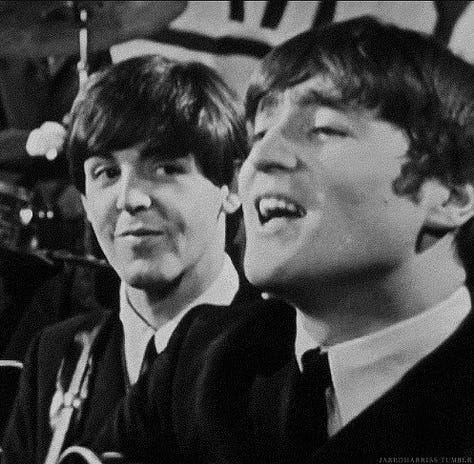

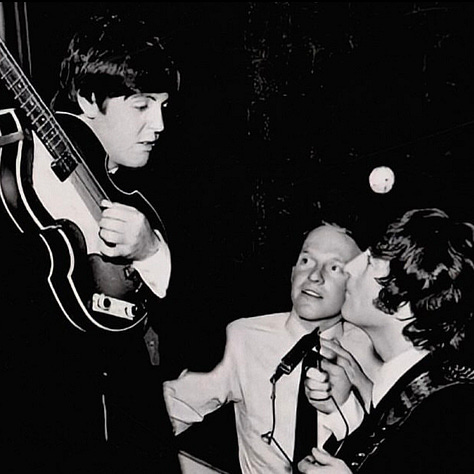

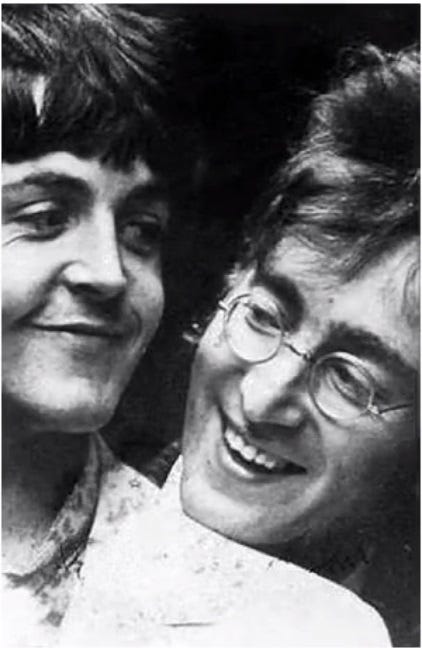

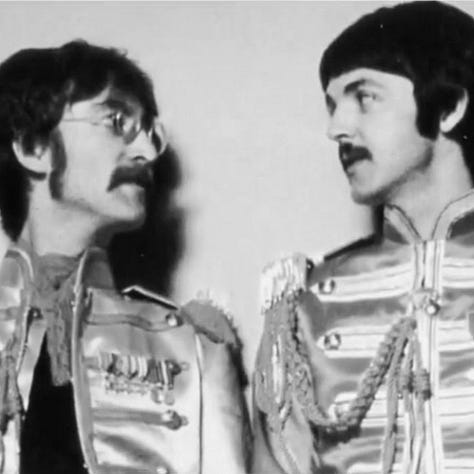

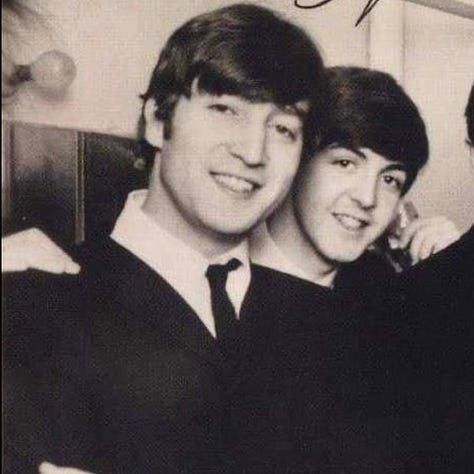

Let’s start with something obvious and easy to see, even if you’re only minimally fluent in the language of the Grail — the way John looks at Paul, from their early days together right through to the Rooftop Concert. There’s a look... and a smile... that John saves only for Paul and that he never once that I’ve ever seen offers to anyone else.

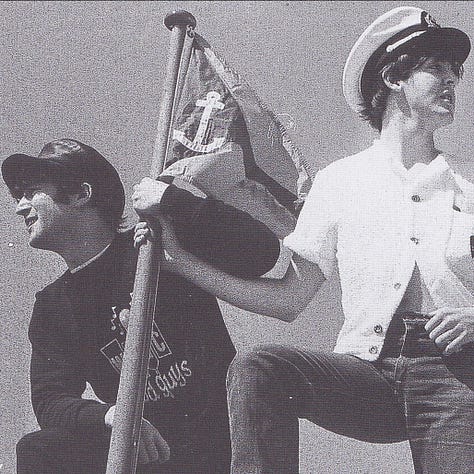

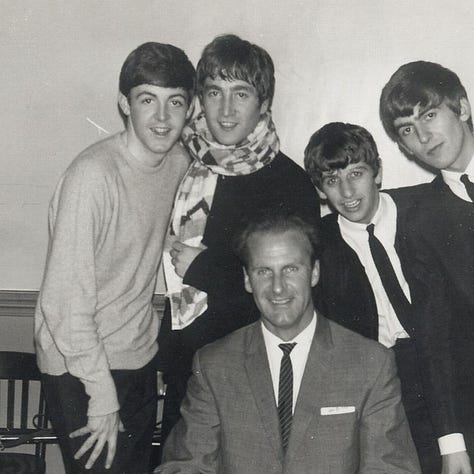

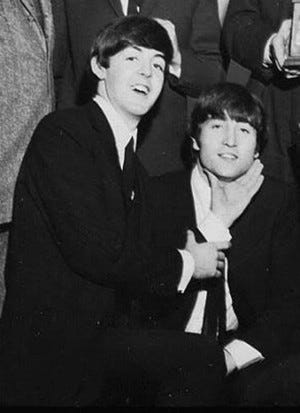

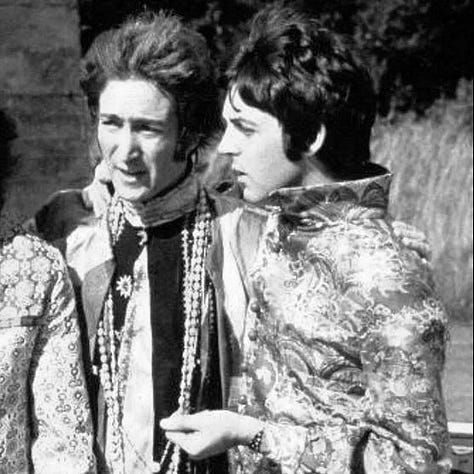

There are many, many photos and videos of John looking at Paul this way. So many that they’re practically a genre unto themselves. Here’s a gallery of some of the most obvious ones—

If you are fluent in the language of the Grail, you don't need my help to see what’s happening in these photos. But of course, right away, we run into a translation problem, in the same way that if you don’t speak French, you won’t understand — or respond to — a book written in French.

If you’re not fluent in the language of the Grail, it will obviously be particularly challenging to see the way John looks at Paul, no matter how unsubtle it is. That’s more or less the whole point of all of this — that the credibility of the lovers possibility is only visible with that softer gaze.

Unfortunately, I can’t reach through the screen of whatever device you’re listening or reading on and help you see it if you don’t. And since this is about emotion, it’s less of a “think about it” thing, and more of a “feel about it” thing.

It’s the thing that John’s art school friend Helen Anderson maybe noticed when she said that “Paul seemed to make John come alive when they were together.”25 And when Rosi, who worked behind the bar at the Kaiserkeller during The Beatles’ first Hamburg residency, told me that “John lit up when he looked at Paul.”26 27

If you can’t see it, one thing that might help is to put your hands over everyone in the photo who’s not John. You’ll probably be able to see... but really feel... the emotion in John’s gaze. If you’re still having trouble, imagine he’s looking at an attractive woman — I suspect that, like the Magic Eye pictures we talked about in the first episode, you’ll see... but really, feel... it immediately.

The way John looks at Paul is not subtle or ambiguous. It’s not a “squint to see it” kind of thing. It’s not a one-time deal where the camera caught an uncharacteristic look that could be misinterpreted. There are dozens and dozens of these photos, all of them of John looking at Paul this way — in a way he doesn’t look at anyone else.28

The way John looks at Paul is not how a man looks at a friend, not even a dear friend. It’s not how a man looks at a brother, and it’s most certainly not how a man looks at someone they don’t even like. John looks at Paul like Paul is the best thing John has ever seen. Like Paul is the centre of John’s universe. Like he’s deeply in love.

Now obviously, Paul either notices the way John looks at him, or he doesn’t. Paul either knows how John self-evidently feels about him, or he doesn’t.

One of the main arguments for discrediting the lovers possibility is that Paul didn’t notice these looks and that he was unaware of John’s feelings for him — that, yes, John was in love with Paul, but Paul was too oblivious to realise it at the time. Some countercultural scholars take it further, and suggest that this is the reason for Paul’s preoccupation with feeling like he never told John he loved him — which we’ll get to when we talk about their songs in the next episode. That Paul didn’t realise that he was in love with John, too, until it was too late, and that this is the pain that haunts him so deeply — that he and John were, to borrow a song title, “the lovers that never were.”29

“John was in love with Paul, and Paul was oblivious until it was too late” is more or less the “starter theory” when it comes to the lovers possibility. And on the surface, it seems solid.

Even if we’ve never experienced it ourselves, we know it’s possible to be completely oblivious to the signals that someone is in love with you — even if those signals are blatantly obvious to everyone else, and even if you feel the same way about them. That disconnect has been a central plot of romance writing and romantic comedy from Shakespeare to Nora Ephron to Red, White & Royal Blue.

The Paul-was-oblivious theory seems solid at first glance, and I certainly couldn't tell you for sure that it’s not true. But it does have a few problems — it doesn’t fit what we see in the photos and videos, it doesn’t fit what we know about the story, it doesn’t fit what we know about Paul, it doesn’t fit what we know about John, and it doesn’t fit what we know about the relationship between Paul and John. But y’know, other than that, it works great.

Let’s unpack it.

John has described Paul, along with Brian, as the person who was most able to steady him when he was at his most difficult and volatile. Here’s John in 1980—

“I should be able to look after myself but I never had, and there was Epstein or Paul to cover up for me. I’m not putting Paul down and I’m not putting Brian down. They’d done a good job in containing my personality from not causing too much trouble.”30

I don’t think we’ll ever completely be able to understand exactly how this “containing my personality” that John talks about manifested itself. That’s probably something only John and Paul would know. But at the very least, it would have required that Paul have the ability to read John’s emotional cues and respond to them in ways that diffused John’s emotional volatility.

And to do that, Paul would have to know what those cues were, in the same way you have to know how a bomb works if you're going to defuse it — and you better really know how that bomb works if you don’t want it to blow up in your hands.

This dynamic between them is something we’re not going to see a lot of overt signs of. By its nature, it would be a private matter, and a subtle one that happened out of view of the public. But we do get occasional glimpses of it.

Paul seems to have had this ability to stabilize John’s more volatile side from the very earliest days of their relationship.

For example, Colin Hanton, the Quarry Men’s drummer, was there for what may have been Paul and John’s first-ever gig together — a battle-of-the-bands contest in which bands were required to pay a cover charge to get in, even if they were competing.

Here’s the story in Colin’s words (edited for length)—

“[John] didn’t like it one bit, paying to play did not sit right with John Lennon... but we did eventually pay to go in — John included, and it was Paul McCartney who convinced John we should do so... Paul’s reasoning was we were more than good enough to win the prize money. He argued that as we would soon be walking off with the cash prize anyway, so we could afford to pay to go inside... So we all did cough up and in we trooped, set up, performed and, of course, proceeded not to win. It was undoubtedly a reality check for our new super-confidant guitarist. We all came away out of pocket, but steeped in admiration for Paul’s enthusiasm and blind faith in the Quarry Men’s ability. He had impressed us all.” 31

There are a lot of things that we could notice about this anecdote. Obviously, it reaffirms what we already know about Paul’s legendary charisma, charm, powers of persuasion and diplomacy. Beatles publicist Derek Taylor, who’s in a position to recognize such things, calls these qualities in Paul an “inborn gift,” and describes him as “a master of communication, unbeatable on personal attentiveness, whether on a one-to-one basis or in front of 50,000 people.”32

This ability is sometimes labeled by detractors as “manipulation,” and maybe it is — but when it comes to how it relates to Paul’s “handling” of John, I think it’s more accurate to call it a preternatural emotional intelligence. It’s notable in Colin’s anecdote, even though Colin doesn’t specifically call it out.

To understand what I mean, in 1967, John talked with biographer Hunter Davies about his insecurities about letting Paul into the band—

“'I was very impressed by Paul playing "Twenty Flight Rock". He could obviously play the guitar. I half thought to myself – he's as good as me. I'd been kingpin up to then. Now, I thought, if I take him on, what will happen? It went through my head that I'd have to keep him in line, if I let him join. But he was good, so he was worth having. He also looked like Elvis. I dug him.'”33

We’ll come back to the Elvis comment in the next episode. But for now, going back to Colin’s story about the pay-to-play gig—

Paul was able, at his and John’s first-ever gig together — when they’re still figuring out their friendship and the power dynamics of the band — to intuitively sense what John needed to hear to convince him to do something no one else in the band, not even those who’d known him for years, could convince him to do. And what’s more, Paul was able to do this in front of the other Quarry Men — with John’s position as leader at stake — apparently without undermining that leadership.

That’s as much about Paul’s intuitive sensitivity to John’s emotional state as it is about Paul's confidence, charisma and persuasive powers (which we all know are considerable).

Here’s Colin again, talking more generally about the bond he observed between them in the early days, soon after they’d met—

“Paul was impressed by John’s personality, his voice, his way with words and wit. John was different, spontaneous and sharp. It was a case of mutual attraction, their individual strengths rounded them off musically, and of course it was John who had the band. Paul was always very diplomatic, however; he always deferred to John. He knew where the boundaries lay.”34

And here’s Helen Anderson, the art school friend of John’s, talking about the lunchtime practice sessions that John, Paul and George would have at the Liverpool College of Art—

“Paul would have a school notebook and he’d be scribbling down words... Those sessions could be intense because John was used to getting his way by being aggressive — but Paul would stand his ground. Paul seemed to make John come alive when they were together.’ “35

Here’s former Quarry Man Eric Griffiths—

“After a while, [John and Paul] would finish each other’s sentences. That’s when we knew how strong their friendship had become. They’d grown that dependent on one another.”36

Here’s Johnny Gentle, aka John Askew, who used The Beatles as his backup band for their first-ever tour in 1960—

“Those two boys operated on a different frequency. I used to watch them work the crowd as though they’d been doing it all their lives—and without any effort other than their amazing talent. I’d never seen anything like it. They were so tapped into what the other was doing and could sense their partner’s next move, they just read each other like a book. It was uncanny… how well they knew each other. It was always Lennon and McCartney, even then. Lennon and McCartney. They wouldn’t even look at George or Stu to determine where things were going. Everything was designed around the two of them—and the others had to catch up on their own.”37

Even at a young age and having only known him for a short time, it seems Paul was able to suss out John’s emotional volatility and devise a way to relate to him — a deferential-but-not-at-all-deferential approach that allowed Paul to be an equal creative partner while keeping John relatively stable. And what’s more, he managed to do both of these things without stepping on John’s need to be seen as the leader, so that John could feel safe in the partnership, the band, and in the world in general.

That’s a remarkably sophisticated balancing act for anyone to master, let alone a 15-year-old boy. And what’s more, Paul seems to have arrived at it instinctively, with no psychological background or resources to draw on — it’s not like he could pop down to the Indica Bookshop and buy a book on how to work productively with your temperamental, insecure, volatile songwriting partner and bandmate.

The reverse also seems to have been true — John seems to have been the one most able to re-centre Paul when he spiralled into worry and anxiety. Again, by its nature, this steadying influence of John on Paul isn’t something we’d see play out in public between them. But again, we do get occasional glimpses of it.

We see John doing quite a bit of “Paul whispering” in Get Back, as well as in interviews throughout their career — including an extended exchange that I’ll leave in the footnotes for you in which Paul starts to spiral into anxiety at having to answer the perpetual “what will you do when the bubble bursts” question, and John steps in and re-centres him by reminding him of their plan to continue to write together regardless.38

Then there’s the anecdote Paul talks about in The Lyrics about recording “Kansas City”—

“Now I’m thinking, ‘this has got to be my best performance ever,’ and I wasn’t doing too well. And John was up in the control room with all the other guys while I was down in the body of the studio doing the vocal, and he walks down for a minute, comes in and whispers in my ear, “Comes out the top of your head, remember?”39

And then there’s the little moment, so quick it’s easy to miss, on an outtake included on the Super Deluxe Sgt. Pepper release. Paul and John are experimenting with the final chord for “A Day in the Life.” Paul is having an attack of the nerves, and John interjects — gently but firmly — with, “stop freaking out, missus.” and Paul immediately settles.40

There’s no way to know for sure the exact contours of the complex bond that they shared — and that’s probably how it should be. But it seems likely that Paul’s ability to read John’s emotional cues — and vice versa — was key to building the trust and intimacy between them that allowed them to write together the way they did and for as long as they did.

Even without considering the lovers possibility, this is why the insistence by several of the more “authoritative” Grail-phobic writers that the Lennon/McCartney relationship, if it existed at all, was strictly a professional one, is so heartbreakingly inaccurate — and maybe a subconscious attempt to steer the story away from anything that would bump up against the lovers possibility.41

If you’ve ever had a long-term creative relationship with another person — as I have — you know it’s an act of intense intimacy and trust.

Like making love, engaging in the act of creation with a partner requires being emotionally vulnerable. For an artist, there’s not much more terrifying than sharing half-finished, half-baked, maybe-terrible ideas with someone in a position to judge their merit — especially if you suffer from intense creative insecurity like John did.

What’s more, creating any kind of art inevitably reveals the secrets of our innermost thoughts and feelings, whether we intend it or not. It’s like the metaphorical version of the naked Two Virgins album cover.

It’s possible to write disposable, for-hire songs without this kind of connection — I’ve done it a time or two myself. But to make Lennon/McCartney happen — to write the songs that changed the world — John and Paul had to be willing to get emotionally and creatively naked with each other, not once or twice or occasionally, but over and over again, for over a decade.

Here’s Paul, talking about that intimacy in a quote we’ve seen before—

“...we looked into each other’s eyes — the eye contact thing we used to do was fairly mind-boggling. You dissolve into each other... (sic) you would want to look away but you wouldn’t and you could see yourself in the other person.”42

John didn’t live long enough to find language like that to describe their creative bond, but we know that they preferred to write together in private, and this creative intimacy is likely a big part of why.

Here’s Paul, as a solo artist, talking about needing privacy to write love songs.

“When you're writing something... as potentially embarrassing as a love song, it's best to hide away in the furthest corner cupboard you can find so that no one can hear you through this process. So I will often literally try and get away so that nobody can hear me do this, because this is...very private. It's got to just be me and this guitar. Then I can touch this sort of inner place where I am the troubadour wandering around in the forest thinking of love, thinking of the beauty of it, the mystery of it, the strength of it... I say it's potentially embarrassing because you know, someone could walk in and go, oh god, you know, and that would be the worst thing.”43

Of course, Paul and John wrote love songs together for many years. So if what Paul is saying is true — and there’s no reason to doubt him — then, by extension, writing a love song with John was the equivalent of writing a love song in private, an act of trust and intimacy.

Here’s Paul again—

“[We] nearly always went up to [John’s] little music room that he’d had built at the top of the house, Daddy’s room, where we would get away from it all. I like to get away from people to songwrite, I don’t like to do it in front of people. It’s like sex for me, I was never an orgy man.”44

Putting aside the possibility of sexual metaphor as a cloaking device for a more literal romantic relationship, they both regarded songwriting as an act of erotic as well as creative intimacy.

Here’s John—

“It’s like a love affair. When you first meet, you can have the hots for twenty-four hours a day for each other. But after fifteen or twenty years, a different kind of sexual and intellectual relationship develops, right? It’s still love, but it’s different.”45

And here’s Paul again—

“That creative moment when you come up with an idea is the greatest, it’s the best. It’s like sex. You’re filled with a knowledge that you’re right, which, when much of your life is filled with guilt and the knowledge that you’re probably not right, is a magic moment.”46

Again, putting aside for now the possible literal meanings of their choice of metaphor, and that both of them reserve their erotic metaphors almost exclusively for talking about one another, that kind of creative intimacy doesn’t happen unless two people are intensely and deeply attuned and trust one another enough to reveal things they wouldn’t reveal to anyone else. Obviously, that kind of deeply bonded partnership doesn’t have to include a romantic element — although it often does — but by definition that kind of mutual trust doesn’t happen in a superficial working relationship.

Great art requires honesty or it’s not great art — and I don’t think it’s possible to write the way John and Paul wrote together, especially given John’s insecurities — eye to eye, looking in a mirror, finishing each other’s lines — unless you’re extraordinarily attentive to what the other person is feeling.

That creative intimacy and trust would have been especially important in the case of Lennon/McCartney. Given John’s extreme issues with abandonment, and his apparent lifelong need to be deeply connected to a single, special person, John would almost certainly have been unable to thrive or work long-term in a creative partnership if he didn’t feel extremely safe.

Here’s John’s childhood best friend and former Quarry Man, Pete Shotton—

“John always suffered from an irrational fear of stepping out on his own. He was accustomed to being the ringleader and the center of all attention, yet nonetheless desperately required the supportive presence of whoever he felt closest to at the time. It would simply never have occurred to him to organize a band from scratch with a group of strangers.”47

By John’s own account, he felt safe with Paul, when he compared their partnership to a stable marriage of two people in love, presumably because he “got” Paul and he knew Paul “got” him — even when no one else did. And someone who has trust and abandonment and self-esteem issues doesn’t get that close to someone without an extreme amount of mutual trust.

The point I’m making — and perhaps over-making — is that John felt safe with Paul, probably because right from the day they met, Paul seems to have understood him in a way no one else did. Paul seems to have seen John in a way no one else ever did.

And given all of this — Paul’s sensitivity to John’s emotional cues, the closeness of their bond, their writing in private, their equating the creative process to sex and physical and emotional intimacy, and the years they spent living in each other's back pockets — it stretches belief to the breaking point that Paul would have failed to notice the way John looked at him. And if Paul noticed how John was looking at him, it stretches credibility that Paul wouldn’t have known John was in love with him.

Now, if Paul knows how John feels, there are, broadly speaking, two possibilities — Paul feels the same way about John, or he doesn’t. And again, the softer language of the Grail helps us out with this one—

If you know your best friend, bandmate and creative partner is in love with you and you don’t feel the same way, the instinctive response — and maybe even the only response, either consciously or subconsciously — is to put some distance between the two of you, for your own sake, for your friend’s sake, for the sake of the partnership, and for the sake of the band.

You’d probably, for example, be hyper-sensitive to physical closeness, and extra careful not to touch the other person unless absolutely necessary. And you’d also probably be careful not to spend hours in private songwriting sessions together. For sure, you wouldn’t spend two weeks in a little Parisian hotel with the other person, or share a hotel room on tour.48

As you know if you’ve ever been in this uncomfortable situation, this instinct towards distance isn’t meant to cause pain so much as to prevent pain. It’s an attempt not to lead the other person on or give them false hope for a romantic relationship that you’re not available or open to.

If Paul knew John was in love with him — which he almost certainly did — and if Paul didn’t return those feelings, he’s more than emotionally literate enough when it comes to John to create distance between them.

But Paul didn’t create distance. In fact, he seems to have done the opposite.

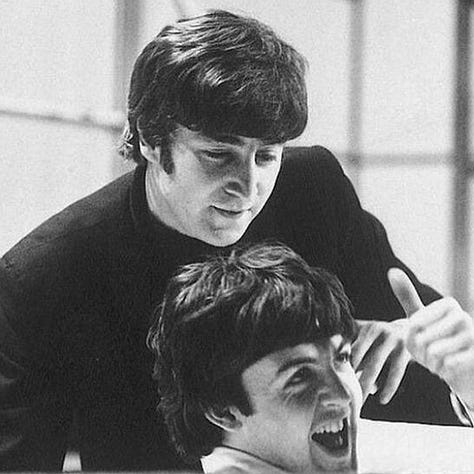

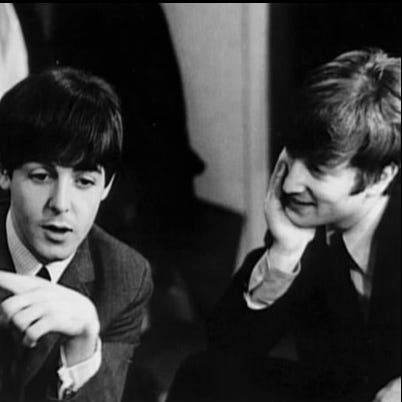

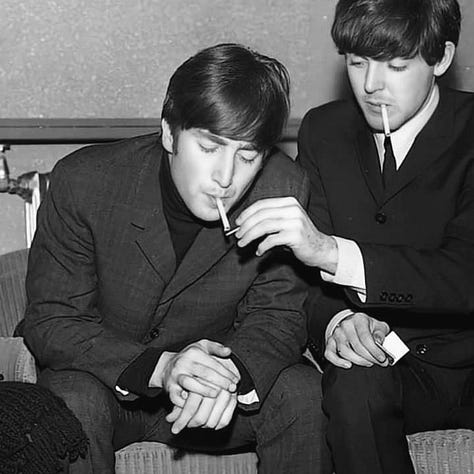

When John looks at him, Paul looks back. He’s less obvious about it than John is, because he’s Paul, not John. But Paul looks back at John in photos and interviews, and onstage with those iconic glances at each other over a shared microphone. Paul looks at John — but really, Paul and John look at each other — through all eight hours of Get Back.49

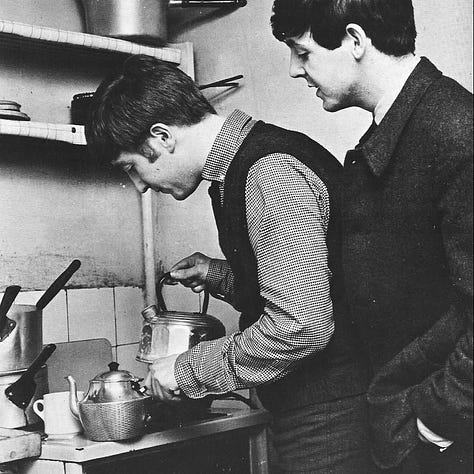

And Paul didn’t just look back. Despite his frequent insistence that he and John never touched because “northern men don’t touch”50 (and that Paul spends so much time talking about this is in and of itself something to notice), Paul and John touched — on camera. A lot. All four of them touched each other a lot, but John and Paul even more so. And more than that, in the photographs and films at least, it’s almost always Paul who initiates the touching.

This isn’t speculation or secondhand reporting or romantic fantasy. There are many, many photos of Paul touching John — Paul’s hand brushing John’s hand, lingering on John’s shoulder, Paul putting his arm around John, sitting on John’s lap, lighting John’s cigarette, playing with his scarf, adjusting John’s tie, fixing his hair. Again, you don’t need to take my word for it—

There’s no practical necessity for Paul to touch John this way or this frequently. They’re bandmates and songwriting partners, not pairs figure skaters or ballroom dancers. There’s no photographer asking Paul to sit on John’s lap or brush his fingers against John’s so they can get a romantic photo for the gossip columns.

And for sure, they didn’t need to share a microphone, at least not once they’d made it to the toppermost. Paul had a perfectly good one on his side of the stage and so did John. And if you’re thinking they needed to share to hear one another’s harmonies, they couldn't hear themselves play their amplified instruments over the screaming audiences, much less the nuances of vocal harmony.

None of this creates distance. And here’s the thing —

If Paul knew John was in love with him — which it seems certain he did — and if Paul didn’t feel the same, and if despite not feeling the same, he looked at John the way he did and touched John the way he did, that would have amounted to something awfully close to emotional cruelty.

I can — just barely — believe John capable of spending years pining after a careful-to-keep-his-distance Paul. But I have a hard time imagining Paul spending twelve years psychologically torturing John, and an even harder time believing John would have put up with that nonsense for twelve minutes, much less twelve years, in the band that he started and made sure everyone knew he was the leader of.

And even if John was so determined to get to the toppermost of the poppermost that he put up with twelve years of emotional cruelty from his co-frontman and songwriting partner, it’s beyond unlikely that their bond would have been as intense or as trusting as it was — or that Lennon/McCartney could have existed at all under those circumstances.

If John was in love with Paul and Paul wasn’t in love with John, and if Paul constantly tormented John by touching him and looking back at him, at the very least, their relationship would almost certainly have been beyond awkward. And that awkwardness would be visible in the photos and videos and to everyone around them — and it just simply isn’t.

So to recap where we are with the credibility of the lovers possibility so far —

John looks at Paul like he’s in love with him. And Paul looks right back, and more than looks, he’s the one who initiates those touches, and he continually seeks out close physical proximity to John — all of which it’s highly unlikely he would have done if he wasn’t in love right back, especially given the intimacy of their bond and Paul’s intuitive understanding of John’s emotional needs.51

So the next question is, if John was in love with Paul and Paul knew it and was in love with John, did they act on that love or not?

Now again, we’re not looking to “prove” that they did — nothing in this line of reasoning would be able to do that anyway. We’re just looking to show that it’s credible that they might have acted on it, which brings us to another objection that’s often made relative to the lovers possibility—

When the possibility of John and Paul as lovers is considered in mainstream “aboveground” Beatles writing, it’s usually presented — or avoided, depending on your point of view — by positing that the lovers possibility confuses the literal with the creative and psychological (the terms “psychosexual marriage” and “romantic friendship” get used a lot these days with regard to Lennon/McCartney — which is at least better than “they only had a professional relationship” or “they never even wrote together at all”).

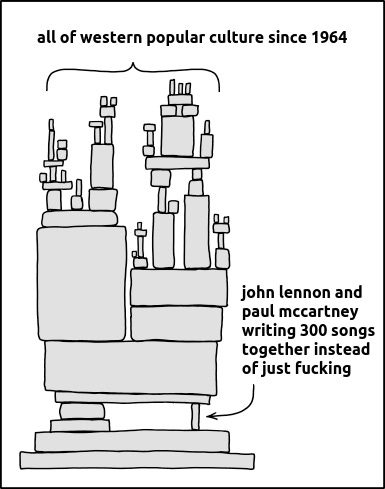

This theory goes that it was John and Paul not acting on their mutual desire for one another that fueled the music and Beatlemania — that all that desire had to go somewhere and that it’s the tension of unconsummated erotic love that accounts for the extraordinary and prolific music of Lennon/McCartney. And that if they’d acted on their attraction, they’d have dissipated their creative energy into sex instead of music.

On the surface, this sounds plausible — very plausible, actually — if for no other reason than unresolved sexual tension is an obvious source of artistic inspiration. More than that, this seems on first blush like the most plausible theory relative to this particular story — John Lennon and Paul McCartney, two of the most famous and desired men in the world, deeply in love during a time when it was illegal and forbidden to express that love directly, pouring all of their erotic passion for one another into the music that would become the lifeforce erotic love that changed the world. Making love to one another through their songs.

That theory has a tragic beauty to it, in the sacrifice of individual happiness for the good of the world — that The Beatles and thus Beatlemania only happen because John and Paul don’t act on their romantic attraction for one another. That it’s this unresolved sexual tension, because it’s unresolved and because it’s so intense between them, that becomes the spark that ignites Beatlemania and thus the Love Revolution.

But while the unresolved sexual tension theory looks shiny on the showroom floor, it doesn’t fare so well on the test drive.

There are lots of reasons for this. There’s the way an actual love affair fits like the proverbial glove into what we actually know happened, and how it resolves almost all the inconsistencies and blank spots in a way that nothing else does — all of which we’ll get to when we re-tell the story in the second part of the series. There are the many things that they’ve said about each other and about their relationship over the years that do not point to an unconsummated love story — things that somehow rarely end up in any of those books. Not the least of which is that if the two of them are in love but not acting on it, then spending two weeks together in a little hotel in Paris would be a fairly extreme form of mutual emotional cruelty — and not something either would be likely to agree to or look back fondly on.