All the episodes of Beautiful Possibility in sequence are here.

The back half of this episode does not require having read/listened to anything prior, but the first half will make a lot more sense (and make for a more beautiful experience of the full episode) if you’ve first read/listened to episodes 1:1 and 1:2.

In a castle, a king lies bleeding.

He’s a good king, a noble king, anointed with the blessing of the goddess. He has no queen.

The king is bleeding from a stab wound to his groin. It’s not a fatal wound, but it is a grave one, because it makes him an impotent king. He can’t do the most important thing that kings are meant to do, beyond ruling the kingdom — he can’t father a child.

Without an heir, his legacy and his power will not live into the next generation. His name and good works will die along with him. He is, it’s said, too ill to live and yet unable to die.1

Beyond the gates of the castle, the once fertile kingdom lies fallow, a Wasteland, bleeding and suffering along with the king. It, too, is too ill to live and yet unable to die.

No traditional cures can stop the king’s bleeding or heal his wound — not his royal physician, nor his court sorcerer, not time nor prayer nor offerings to the gods. Only one remedy can heal the king and save the kingdom.

Every evening, a young maiden silently carries a golden chalice — a Grail — through the banquet hall, where the nobles of the court are feasting. Penetrating the Grail, supported by nothing but air, is a bleeding lance. To heal the king requires only that someone notices the Grail procession and asks after its purpose.

But no one asks. The nobles at the table are too busy gorging on the king’s rich food and wine to offer their attention, and the occasional traveller who arrives at the castle gate seeking hospitality is too polite to mention the odd procession through the hall.

Months pass. Then years. Then decades. And still the king lies bleeding.

This is the earliest-known telling of the legend of the Fisher King and the Grail, another of Western culture’s most important mythological stories, though unlike the story of The Beatles, almost certainly fictional.

Most people think of the legend of the Grail as a Christian story — or maybe a Monty Python movie — but there’s good reason to think it originates from pagan traditions that predate Christianity by hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years.2 When it comes to mythology, though, it matters less what a story was, and more what it has become. And over the past thousand years, the Fisher King and the Grail has become one of the most important — if not the most popular or well-known — mythological stories in the Western world, in part because it offers a simple and profound set of instructions for how to heal a wounded culture.

We’ve covered a lot of ground in the first two episodes, getting to our own wounded culture — about two thousand years’ worth. Given where this episode is headed, I suspect some of you may be tuning in to Beautiful Possibility for the first time with this episode, so let’s briefly recall where we are in our story about the story of The Beatles.

By the early ‘60s, not just Western culture but the whole world had been through a near-relentless generations-long death march — and not just the perpetual death march that goes hand-in-glove with “might makes right,” but the most extreme and gruesome manifestation of the death force in history. Over 20 million people killed in World War I, over 50 million people killed in World War II, including over six million people killed in the Holocaust, two hundred thousand people killed by the atomic bomb — and with it, the new and unprecedented threat of the destruction of all life on earth if someone has a bad day and pushes the wrong button. All of it punctuated by the assassination of a young, idealistic American president. And that’s not even a complete list.

At the end of 1963, virtually everyone on the planet had been forced to confront, in some form, violent death on a previously unfathomable scale.

Most of the older generation coped the way most people do, when trauma is chronic and they still have to get up every day and go to work and care for their families, and in the absence of any therapeutic or cultural support to deal with it. They went into denial, pretending nothing was wrong and everything was fine, and let’s just keep calm and carry on the way everything has always carried on and not think too much about all of it.

The kids, on the other hand, always hardest hit by the death trauma of war anyway — and on top of that, having grown up with nightmares of atomic annihilation — coped by screaming their heads off to the cathartic rhythms of early rock and roll, though only for a few short years.

Early rock-and-roll blazed through the culture like a fast-moving prairie fire, but history shows us it lacked the necessary extra something — the X-factor, let’s say — required to spark, and more importantly, sustain and grow a riverbed-changing revolution and a new mythology, and thus a new culture.3

Changing the world requires a new story, not just the rejection of an old one, and despite the younger generation’s extreme dissatisfaction with both “suffer now, rewards later” and “might makes right,” at the dawn of the new decade of the '60s, no new story had arisen that was powerful enough to replace either.

The cultural earthquake of the Sixties — sparked and led by The Beatles — gave us that new story, and created a new and better world that we refuse, quite correctly, to let go of, even if all we got was a whirlwind romance with the Love Revolution before it all came crashing down.

The breakup of The Beatles, in part because of the distorted story that formed around John’s desperate and angry breakup narrative, tore a jagged hole in that new world when we lost our faith in the power of love. That loss of faith manifests itself in the fragmented, disoriented, chaotic culture we’ve been trapped in ever since.

Those of us who engage deeply and emotionally with the story of The Beatles tend to feel this wounding more consciously and more acutely. Those who don’t engage as deeply or as emotionally — or not at all — still feel the wounding as an underlying existential dis-ease, even if there’s no conscious understanding of the cause, because that’s how mythology works—

When the foundational myth of a culture is wounded, the culture itself is wounded, and so is everyone who lives in that culture. A foundational myth distorted by rage and pain is a slow-acting toxin that contaminates the “river” of a civilization and poisons everything and everyone touched by that river — whether we’re aware of the toxin or not.

At the end of the prior episode, I suggested there might be a way to heal the wounded story of The Beatles and of the Sixties, and thus to begin to heal the wounding in all of us. That there might be a way to restore our belief, born out of the Sixties, that the power of love really can change the world — which brings us back to the legend of the Fisher King and the Grail.

In the legend of the Grail, the Fisher King’s wound can only be healed by an act of attention. Someone has to notice the Grail and ask about it. This is common sense, really, more than mysticism or magick, and it suggests that we’re in very good hands looking to the Grail story for guidance. We obviously need to pay attention to a wound — we literally need to notice it’s there — before we can do anything to make it better.

So in this episode, we’re going to continue our careful work of paying attention to the wounding of our world caused by the breakup of The Beatles and the collapse of the Sixties — and by the first generation of Beatles writers who believed John’s angry, false narrative about both. In contrast to the bleakness of the prior episode, this episode will lead us to what might be the most beautiful place we’ve been so far in all of this — the specific nature of the love at the centre of the Love Revolution and the new world it created.

For those of you who have already sussed out where all this is going, this is the episode you’ve been waiting for and thank you for your patience. For some of the rest of you, this may be an unexpectedly challenging episode, despite it being all about love, and I ask for your patience and your open-mindedness. We’re only just getting started together on this journey and once we get past a few bumps in the road, you’ll find it will take us to some quite unexpectedly profound places — all of them intimately bound up with the healing power of love.

So with that said, let’s go search for the Grail.

“We all been playing those mind games forever

Some kind of Druid dude, lifting the veil

Doing the mind guerrilla

Some call it magic, the search for the Grail.”4

— John Lennon

The Grail is one of the most complex mythological symbols in human history and we’re not likely to define it in just a few short sentences. Most Grail scholars (and to be clear, I am not a Grail scholar) agree that the power of the Grail relates in some vital way to love. But what kind of love are we talking about, exactly, when we say the Grail — or for that matter, the Love Revolution — is about love? “All you need is love” sounds good in a song, but it isn’t all that helpful, when there’s a wound bleeding out all over the floor of the castle.

The problem is that “love” is such a frustratingly vague word. It’s become almost meaningless, the way we use it to describe our feelings for our friends and family, our romantic partner, maybe whatever we call God, and also our affection for tacos. And then there’s the more diffuse and abstract “love for humanity.” Surely those can't all be the same kind of love? And which of these many kinds of love might be represented by both the Love Revolution and the Grail? It probably isn’t the love of tacos — even really, really good tacos.

Many Grail scholars, especially those who come from more conservative academic or religious traditions, suggest that the love represented by the Grail is chaste, spiritual love in the form of a pious devotion to God. But Grail scholars, like Beatles scholars, have a habit of ignoring inconvenient truths, and what the “chaste spiritual love” crowd ignores about the Grail story is the inconvenient presence of the Lance.

A lot of people don’t know there’s a Lance in the Grail story (if you don't remember it from the opening of the episode, you’re in good company). But there is and it’s, well, very lance-y — long and hard and erect, its tip dripping with blood in the earliest version of the story that we have, but perhaps dripping with something else in its original incarnation — penetrating deep into the obviously feminine form of the Grail.

That description probably makes it self-evident that saying the Grail represents spiritual love is something of a polite euphemism, much like describing the Fisher King’s injury as a “groin wound.”

Medieval audiences had delicate sensibilities, you see, not unlike some audiences today — so medieval poets mostly ignored the obvious symbolism of the erect Lance penetrating the — we don’t have a poetic word for this exact combination, but — the uterus and vagina-shaped Grail, just like those same medieval poets ignored the inconvenient detail that the Fisher King’s wound isn’t a “groin wound” or even a wound to the heart, it’s a wound to the genitals.

Uptight medieval poets and academic Grail scholars can contort themselves into denial all they want, but there’s no reasonable way the Fisher King legend is about the healing power of chaste, spiritual love — and not just because of the obvious symbolism of the Lance and the Grail, but because spiritual love isn’t in and of itself actually a cure for a wound to the genitals. Try telling a man with a serious injury to the... groin... that all he needs to do is pray and everything will be fine, and see how far you get with that.

Remember the Grail began life as a pagan symbol, and pagans were very much not uptight about sex, in part because they knew sex was one of the most powerful ways to connect directly with whatever you want to call God.

If the Fisher King’s wound is a wound to his genitals, which it clearly is, and the Lance and the Grail are having symbolic sex, which they clearly are, then the healing power of the Grail isn’t spiritual love, it’s erotic love — the kind of love that’s primarily expressed not through prayer and chaste piety, but through the fire of sexual passion, which in turn makes the Grail a literal sex symbol and the legend of the Fisher King a story of sexual healing. And this is why we’re talking about this relative to The Beatles and more specifically, Beatlemania — because Beatlemania was self-evidently about sex, and sex is, of course, about a lot more than just sex.

Sex, at its most basic, is obviously biologically meant for reproduction. Conceiving and giving birth to physical offspring is nature’s way of creating new life. And giving birth to new life is, of course, the most literal and instinctive way to counter death.

The post-World War II baby boom — and there is always a baby boom after a war, but this one was especially big — was a global example of this instinct to heal death with new life. A post-war baby boom is usually explained as soldiers coming home from war — and probably even more, the sweethearts they left behind — being impatient to start the families that had been delayed because of the war. And while that’s true, it's also a bit spicier than that, because of course sex is about more than baby-making, especially when it's with someone we love.

And now we come to a fundamental — and very hopeful — truth of how humans and mythology have danced together throughout history.

Mythologically, psychologically, in the fragile, ever-changing fortunes of the human heart, when we’re suffering under the heaviness of death, we instinctively reach for life. And despite what the anti-sex religious crowd would have us believe, nowhere is the power of new life in the face of death stronger than in the ecstatic, life-giving passion of erotic love.

I hope you’re fortunate enough to know firsthand that really great sex with someone you’re deeply in love with (and who’s deeply in love with you) tends to be especially intense and ecstatic — physically, emotionally and spiritually. Great sex of course needs no explanation. And when we’re having that great sex in the arms of someone we’re in love with and who’s in love with us, we’re not just having sex, we're making love in the most literal sense. We’re connecting with the life-affirming power of both romantic love and sexual passion. And the combination of romantic love and sexual passion creates an ecstatic feeling of new life within us, whether we’re trying to make a literal baby or not.

When we make love — with everything that phrase suggests — our spirit is renewed and we are, in a very real way, reborn into a new and heightened sense of awareness.

You might have had the experience of what the world looks and feels like after making love, especially for the first time, with your beloved — the way everything feels new in some way that’s hard to define, but undeniable. The way even ordinary things take on a kind of life that they didn’t have before, from your morning coffee to the feel of the sun on your skin to the usually routine commute to work.

This is what we mean when we say that someone who is newly in love is glowing. That “glow” is the glow of new life pushing up through the once-fallow ground of our spirit. And one of the strongest ways new life finds its way into our world is through the life-giving power of erotic love.

A colleague of mine, religious studies professor Arthur Versluis , calls this life-giving combination of sexual passion and romantic love “love-fire-life.”5 French theologian Jean-Yves Leloup calls it “sex with wings.”6 It’s the kind of unusually intense and ecstatic erotic love that the pagan world knew had the power to lift us into a higher place. And it’s probably where the fundamentalist Christian idea of being “reborn into the love of Christ” originally came from — before erotic love was labelled corrupt and sinful and stripped out of that story in favour of “suffer now, rewards later,” the antithesis of the power of erotic love.

Our Western rationalist culture doesn’t value or even explicitly acknowledge this sex-love-life combination. And since we tend not to name things we don’t value or acknowledge, we don’t have a good word for it, which is why we come up with things like “love-fire-life” and “sex with wings.”

For our purposes, let’s call it “lifeforce love,” which is a bit less poetical but a bit more descriptive. It still doesn’t get us anywhere near its world-creating transformative power — I doubt there’s a single word or phrase in any language that could — but at least it puts what we’re trying to define in direct opposition to the death force that, by its nature, it pushes against.

Lifeforce love is almost certainly the healing, regenerative power offered by the Grail, but really it’s the combination of the Grail and the Lance. It’s also the reason the Grail’s power often gets confused with spiritual love for God. It’s the necessary spark at the inception of all acts of creation, whether it’s the literal conception and birth of a new baby, or the creation of a new song or painting or an invention or an idea, or ecstatic, blow-your-mind-out-in-the-backseat-of-my-car sex with someone we’re passionately in love with and that plugs us directly into the fiery “big bang” creation energy of the universe. The life-creating erotic love that — if it’s strong enough and if there’s enough of it — might even be powerful enough to spark an earthquake that gives birth to a new world.

It’s going to be really important to understand that what I’m talking about here is more than just garden-variety (although still wonderful) romantic passion — which does not generally create new worlds for anyone but the two people involved.

And since I seem to have run out of words to fully make that point, I’m going to borrow some from writer Elizabeth Scalia writing in 2019 about Beatlemania (edited for length) —

“The bald joy is no small thing. In fact, it’s incredibly powerful... It’s like watching a struck match being thrown with abandon into the mysterious fuel of God’s eternally aflame creative energy; it brings forth a full-on encounter with the deepest essence of another which has been willingly, almost recklessly and needfully exposed out of a compulsion to consume and be consumed within this driving love. When what is being exposed is the naked joy of consummation and fulfillment, the girls can’t help it; the boys can’t help it. Everyone screams.”7

This fiery, transcendent sex-love-lifeforce is the restorative, life-giving elixir the grey shell-shocked post-war world of the 1950s was desperately in need of, to heal a culture numbed by the trauma of violence and death. And it’s the life-giving regenerative love our world today is in desperate need of, in the wake of the collapse of the Sixties and the chaos and social disintegration we’ve lived through ever since, that seems to be escalating with each passing year.

The legend of the Grail reminds us that when a culture suffers from a Fisher King wound, it loses its connection to this erotic lifeforce love, represented by the Grail (in combination with the Lance). The culture becomes impotent, too ill to live and yet unable to die, incapable of nurturing or sustaining meaningful, life-affirming growth or change.

And until that wound is healed, any effort to create sustainable, long-term change — through art or music or social reform or political action or even the awesome power of social media hashtags 🙄 — is virtually destined to fail. The world is, essentially, stuck. And when the lifeforce of a culture is stuck, it inevitably decays and becomes barren and sterile. Nothing can grow or change or heal. It becomes, as in the Grail legend, a Wasteland.

Mythologist Joseph Campbell describes the Fisher King’s Wasteland this way—

“In the Wasteland, life is a fake. People are living in a manner that is not that of their nature; they are living according to a system of rules. And this is represented in turn by a wounded king whose wound has turned the whole country to waste.”8

Does this sound familiar? Beyond the obvious parallels with the current... situation, in our modern world, the “system of rules” is the toxic mythologies of “suffer now, rewards later” and “might makes right.” And the Wasteland is what our culture has been slowly decaying into, as anything stripped of its lifeforce decays — beginning with the collapse of the Sixties and the breakup of The Beatles, slowly but steadily bleeding out into the.... I mean, no one has yet coined a better phrase than “dumpster fire” we’re living through now.

I hope maybe you’re starting to see why healing this story matters so much.

KURT VONNEGUT: The function of the artist is to make people like life better than before.

INTERVIEWER: Have you ever seen that done?

KURT VONNEGUT: Yes, The Beatles did it.9

It’s one of my favourite parts of the story of The Beatles — that it’s the children of the post-war Baby Boom, born out of the death trauma of the war and the Holocaust and raised in the shadow of the atomic bomb, who would become the teenagers and young adults who would spark Beatlemania, and in turn, the Love Revolution, the most powerful eruption of lifeforce love in recorded history. And like the post-war baby boom, the Love Revolution, beginning with Beatlemania, was without a doubt fueled by this lifeforce love — the healing erotic power of the Grail.

When we think of Beatlemania, we usually think of those post-war Baby Boom teenagers, who had the privilege of being the first generation to lose their minds over The Beatles. The screaming and fainting, the wet seats after concerts, the contorted expressions of ecstasy and sometimes agony on their faces, the desperate attempts — some of them downright terrifying — to gain access to the Beatles’ hotel rooms. And in some ways, most telling, the tidal wave of letters written to The Beatles by teenagers offering themselves — including often their virginity — as tribute and sacrifice to these new and powerful gods of erotic love.

Of course, teenagers screaming for their idols wasn’t in and of itself new. Kids had screamed for Elvis, and before that, for Frank Sinatra, and during the Swing Era, for the Benny Goodman Orchestra, and no, I am not making that last one up.10

Beatlemania was something altogether different.

After the long, dark night of two world wars, the Holocaust, the atomic bomb and the assassination of a young American president, Beatlemania engulfed the world in an ecstatic explosion of music and joy and sexual awakening unlike anything the world had — or has — ever experienced, lighting the fuse for what would become the Love Revolution of the Sixties.

Beatlemania dwarfed everything that came before — or since — in scale and intensity and longevity, as it spread rapidly across multiple generations and over most of the globe. Sixty years later, Beatlemania remains a singular phenomenon that’s never come anywhere close to being repeated.

It wasn’t only the scale and intensity and longevity that were unique about Beatlemania. The way in which teenagers around the world reacted to The Beatles was markedly different from the reactions to Elvis and Frank and Benny, though it might look the same on casual glance.

There was an intensity — and even a violence — to Beatlemania that was entirely absent from prior eruptions of teenage lust and euphoria — a near-primal ferocity, as if they were dying of thirst and desperate to get to the only water in the desert.

We’ll talk more about that reaction in a little while, but for now, even as we’re all in agreement about its seismic cultural impact, we still don’t have a satisfying and accurate explanation for why Beatlemania was what it was.

Most writers do what mathematicians playfully do when they don't yet know how to solve a proof, inserting “and then a miracle happens” for what they aren’t able to explain — “First, there were The Beatles and then a miracle happened and then Beatlemania and then another miracle happened and then The Sixties.”

The thing is, though, in important ways, that is more or less exactly how it all happened. “What was it about The Beatles?” is to some extent an unanswerable question, and that’s probably how it should be.

Beatlemania was, by any reasonably open-minded definition, a miracle — if a miracle means a great blessing that we have no scientific explanation for. And how do you explain a miracle? How do you deconstruct magic? And do we even want to try? Isn't it perhaps more magical if The Beatles remain mysterious and ineffable in the same way a magic trick is only magical when we don’t know how the trick works?

There’s always risk in a quest to discover the source of magic — otherwise, it wouldn't be much of a quest.

But in this case, it might not be quite the risk it seems to be, because there’s magic and then there’s magick. There’s trickery and sleight of hand and the “man behind the curtain” magic of the illusionist — and then there’s that other kind of magick, the real kind that we know in our hearts is at the centre of this story and this music. The kind of magick we find when we look with the softer gaze of mythology. The kind of magick contained in the lifeforce love of the Grail.

Unlike the hard, rational stare of history and journalism, mythology draws on this deeper magick, found in the subtleties of the human heart and the human spirit, in fairy tales and folklore, enchantment and mystery, which I’ve come to believe is where this story belongs — and which is perhaps the only way to truly understand and connect with its deeper power. And most important for us, perhaps the only way to heal the wound at its centre.

For the vast majority of people I’ve talked with about my work on this series over the past few years, discovering the deeper magick at play behind all of this has made the story — and the music — richer, more beautiful and more magickal. And since I’m on a bit of a personal quest to restore the deeper magick to this story, I hope with all my heart that you'll feel the same.

But that said, if you really, really don’t want to know how the magick of Beatlemania might have happened, now’s the time to leave the theatre. For the rest of us, I invite you to come along on our — you knew we were going to say it eventually — magical mystery tour and see what we might discover.

“Must’ve been a lot of magic, when the world was born.”11 — Paul McCartney

Let’s put the pieces that we have so far together.

Lifeforce love is by definition the only thing that heals a death trauma. And the description of lifeforce love — as best as I’ve managed to find words for it — is also an accurate description of Beatlemania. And since it was Beatlemania — and thus The Beatles — that sparked the Love Revolution, that obviously means that the source of that lifeforce love is The Beatles. And lifeforce love is, remember, erotic love, love that creates new life — either literal or creative.

That in and of itself isn’t unusual. Lots of things are the source of lifeforce love. All art, including and perhaps especially music, is inherently infused with at least some lifeforce love or it couldn't exist. And so is all of what gives us true and deeper joy rather than just passing pleasure or escape, whether it’s making love with our beloved or romping in the park with our dog or immersing ourselves in a creative project or connecting to whatever higher power we might choose to call God.

It’s once again a matter of scale.

The Beatles were, to say the very least, an unusually powerful source of lifeforce love — arguably the most powerful source in recorded history, given they’re the only ones who’ve managed, in the span of just a few short years, to displace “suffer now, rewards later” and create a new world.

So what’s the specific source of lifeforce love in what The Beatles were giving the world in 1964? It could be as simple as their musical genius — but they weren’t history’s first musical geniuses, and none of the other geniuses managed to spark a riverbed-changing cultural earthquake. So it could be that, but it’s probably not just that.

What, beyond the obvious fact of their genius, is the X-factor that made it possible for four boys from Liverpool to do what no one else in two thousand years has ever done?

This is the deeper mystery at the heart of the story of The Beatles, the one that goes far beyond the surface inconsistencies and contradictions.

And what makes it all even more mysterious is that when manager Brian Epstein replaced the overt sexuality of their black leather with tailored suits and a fresh-faced “boy next door” veneer of respectability before launching them into the wider world, the reaction to them got even bigger, more intense, more ecstatic, until it swept across the globe in a firestorm of teenage lust and longing like no one before — not Elvis, not Frank, not even Benny Goodman — nor anyone since has ever done, not even artists who were far more overtly sexual onstage then The Beatles.

One reason none of those more overtly sexual artists managed to spark a world-changing revolution might be that they were raising the wrong kind of sexual energy — or to put it in the language of the Sixties, they were giving off the wrong kind of ‘vibe.”

To understand why, we need to talk about sex, revolution and early rock-and-roll.

Anything that connects us directly to the lifeforce is inherently dangerous to institutional power, and especially to religious institutional power, because the ecstasy of being connected to the lifeforce directly ourselves means we don’t need what the powers-that-be have to sell. If money can’t buy love, it sure as hell can’t buy the ecstatic joy of lifeforce love.

Sex has always been the most dangerous and powerful conduit of lifeforce love, because it’s such a direct and literal manifestation of it — which is why religious authorities tend not to want people to have sex, and if we insist on doing it anyway, they’d prefer we didn’t enjoy it. After all, if we discover that sexual ecstasy can connect us with the transcendent power of lifeforce love — aka the power of creation, aka the power of God — then, as the Flower Children figured out in the Sixties, what do we need the Church for?

But obviously, there’s a limit to how much control religious authorities have over sex. They can’t stop people from having it altogether, and even if they could, they still can’t, because whether the uptight brigade likes it or not, sex — and here I’m talking about garden-variety heterosexual procreative sex — is how we make more humans, so a civilization wouldn’t survive more than a single generation without it.

Since the powers-that-be who constructed the whole “suffer now, rewards later” marketing campaign for Christianity couldn't get rid of sex entirely, they did the next worst thing — they made rules about who could have sex and how, and then told everyone that if you have sex outside of those rules, you won’t get into Heaven. Basically, try and get your rewards now, and you’ll suffer later.

As for the rules, however open-minded the pagans had been about lifestyle experimentation, the first earthquake of Christianity made it very, very clear that the only kind of sex that was going to be acceptable moving forward was “boy meets girl” — and even then, only within the bonds of holy matrimony and only for the purpose of making more little Christians. And for the next two thousand years, that’s more or less how it was. Traditional — and tightly constrained — heterosexual baby-making sex was the only culturally-approved kind of sex. And you still weren’t allowed to enjoy it (especially if you were female).

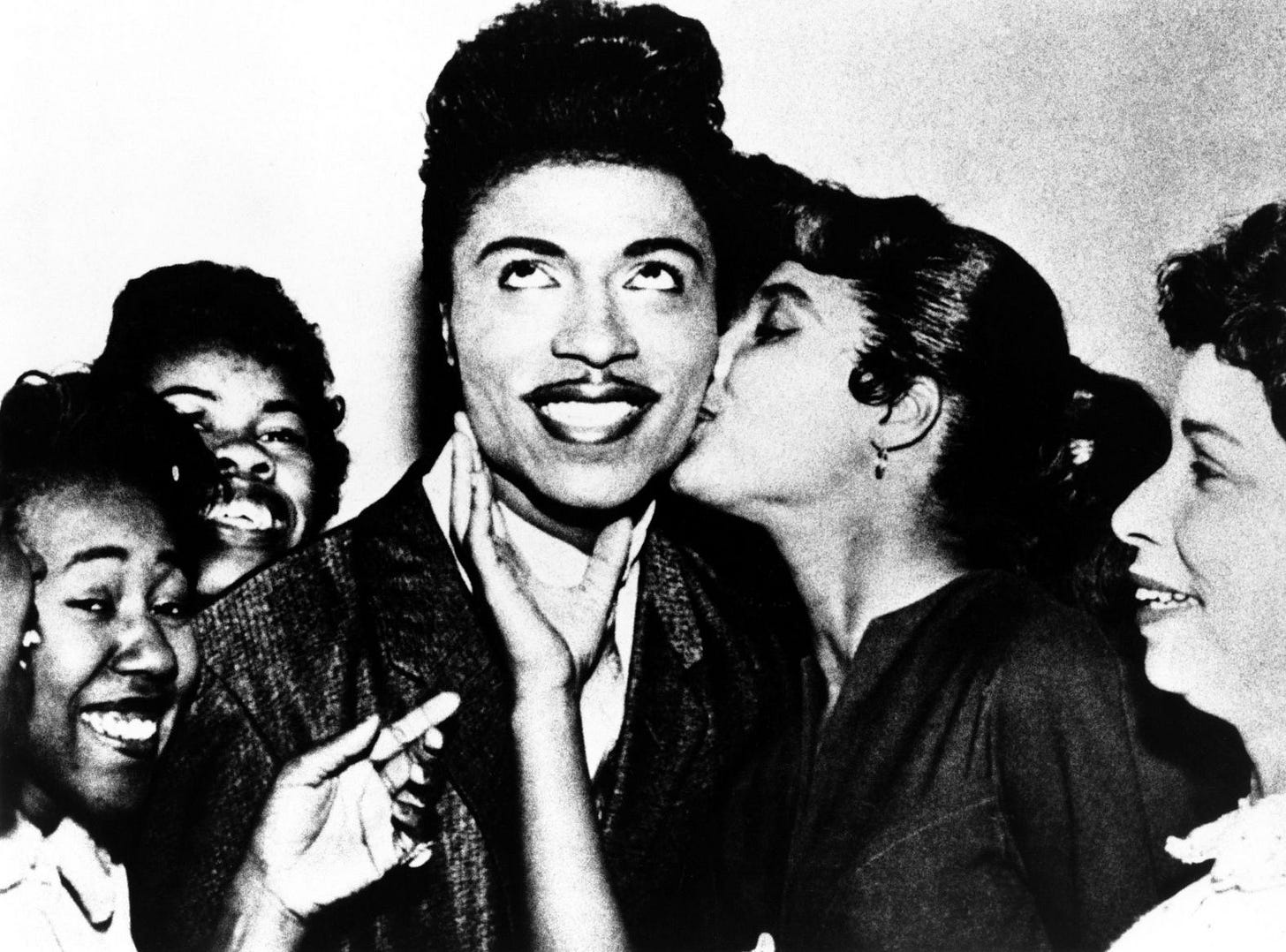

Early rock-and-roll— mostly in the form of Elvis and also to some extent Little Richard — pushed the boundaries on these rules. Here’s Sixties cultural critic George Melly on Elvis’ appeal (edited for length) —

“Presley’s breakthrough was that he was the first male white singer to propose that fucking was a desirable activity in itself and that, given sufficient sex appeal, it was possible for a man to lay girls without any of the traditional gestures or promises... [Presley] came on as though confident in his ability to attract women without appealing in any way to their protective instinct. He was the master of the sexual simile, treating his guitar as both phallus and girl, punctuating his lyrics with the animal grunts and groans of the male approaching an orgasm. He made it quite clear that he felt he was doing any woman he accepted a favour. He dressed to emphasise both his masculinity and basic narcissism, and rumour had it that into his skin-tight jeans was sewn a lead bar in order to suggest a weapon of heroic proportions.”12

I can’t speak to the truth of the lead bar situation, but as with the brick through the window during The Beatles’ breakup, it’s the kind of thing that sounds like it could be true. And that tells us most of all we need to know about the sexuality Elvis was putting into his performance, and thus into the culture.

Elvis was scandalous in that he brought sex to the surface as something to do not just for babies, but for pleasure and for power — which definitely violated the rules of “suffer now, rewards later.” But as sexually inflammatory as pre-Army Elvis was as a performer, he was nonetheless modelling traditional, culturally-sanctioned “boy meets girl” heterosexuality. And his performative sexual arrogance was the arrogance of America in the 1950s. The country that had won the war and saved the world with the most awesome display of “might makes right” the world had ever seen was now demanding the spoils of war — and those spoils included your teenage daughters.

This matters because the erotic lifeforce power required to spark a riverbed-changing revolution and change the underlying mythology of a culture by definition has to push against the prevailing values of the culture, in the same way that if we want to change the direction of the river, we can’t just send a bunch more water down the same riverbed that already exists. All that would do is make the existing riverbed deeper and wider, more of what it already is.

To put it another way, adding more of something that’s already there doesn't disrupt the pattern of a culture, it reinforces it.

Adults were scandalised by Elvis’ more overt and aggressive sexuality, and at the shocking discovery that teenagers were having premarital sex. But none of that was all that different from the norm. Teenage sex, Elvis-style, was really just a sin of overzealous, premature heterosexual sex. It was scandalous not because it went against the existing values of the culture, but because it exaggerated them.

It’s not a coincidence that in the ‘50s, Elvis was sometimes promoted as “the Atomic Singer.”13

And this leads us to…

“The white kids would have Pat Boone up on the dresser and me in the drawer ‘cause they liked my version better, but the families didn’t want me because of the image I was projecting.”14 — Little Richard

Little Richard, a queer black man whose music and sexually-ambiguous stage presence was overtly and flamboyantly erotic, unquestionably had the transgressive sexual firepower required to push hard against the culture.

But history shows us that Little Richard didn’t spark a world-changing revolution, either. Far from it. Little Richard struggled for most of his life to get his music to the mainstream, and without getting the message to the mainstream, there can be no revolution of any kind.

In addition to his habit of sabotaging his own career with his personal demons, it’s tempting to blame Little Richard’s “failure to thrive” on the racial and sexual prejudice of the 1950s. That prejudice undoubtedly kept black and openly queer artists from the full career opportunities that they should have had access to.

But for our purposes here, looking at this through a mythological frame, Little Richard’s story is more complex than that.

Like Elvis, Little Richard was a huge talent and pivotal to the history of rock-and-roll. In pagan and in many indigenous cultures, his transgressive gender-bending sexuality would have made him a powerful and revered shaman. And he would have dazzled as a provocative, outspoken advocate for queer liberation in the ‘70s and ‘80s — when he wasn’t otherwise occupied denouncing homosexuality in the name of Jesus, that is.

But a revolution that actually changes the world requires reaching beyond the revolutionaries. And in post-war Western culture, a black man performing queer sexuality was not going to be welcomed into the living rooms and bedrooms of white suburban families — at least not on the scale required to spark a riverbed-changing revolution.

This was the era when, in America at least, even traditional male-female married couples on TV were still being shown sleeping in twin beds, if they were shown together in a bedroom at all.15 And of course, the 1950s was also an era of widespread, publicly-sanctioned institutional racism. Put those two together, and a black man even flirting with a white woman wasn’t just scandalous, it could get him lynched.

Here’s Charles Connor, who was a member of Little Richard’s band in the 1950s—

“A lot of places we played down South, like Amarillo, they locked Richard up [to keep him] from shaking [his] hips on the bandstand. They’d stop the concert and throw him in jail. Richard’s road manager would have to pay a fine, $150, $200. And then they’d say, ‘You better not come back here shaking your hips like that, boy.’ I’ll never forget that night, because when they let him out, they said, ‘There’s another guy coming here. His name is Elvis Presley. If you see Elvis Presley, tell him he’d better not bring his redneck behind here shaking and acting the fool on the stage like colored people. ‘Cause we’re gonna lock him up, too!’ Because Elvis was shaking his behind on The Ed Sullivan Show, but in Amarillo all it meant was a white man acting like a black man, and they couldn't have that.”16

In the racially bigoted and sexually repressive cultural climate of the ‘50s, white teenagers were not going to be allowed to perform public sexual hysteria for a queer black rock-and-roller. Nor were parents going to allow a queer black rock-and-roller into their living rooms, radiating the full force of his queer black sexuality on, say, The Ed Sullivan Show.17 Nor would most white suburban parents have allowed their kids to put up a queer black man’s poster on their bedroom wall or attend his concerts.

And if, in spite of all of that, massive numbers of white teenagers had defied cultural norms and Little Richard-mania had broken out, the white authorities, panicked and terrified at seeing their kids worked into a sexual frenzy by a black man (and a queer one at that), would have clamped down — hard. And the clash that would have followed — as we know from the white establishment’s brutal response to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s — would have ended in something quite the opposite of a Love Revolution.

If Elvis was too sexually mainstream, then Little Richard’s transgressiveness was too much too soon, sexually and racially, to be able to spark a culture-changing revolution in a world that wasn’t quite ready — and wouldn’t be ready until after the revolution of the Sixties — for his incendiary brand of sexuality. And by then, the music had moved on. The tragedy of Little Richard is that he was born a generation too early to be everything he could have been.

Both Little Richard and Elvis were, of course, important to the history of rock-and-roll. And their influence on The Beatles’ story and on their music is obviously significant. Without Elvis in particular, it's possible The Beatles might not have happened. And the world would be a poorer place without Paul McCartney screaming “Long Tall Sally” into the heavens at Shea. But those who inspire revolutionaries are not necessarily successful revolutionaries themselves, and that’s where we often get confused.

Transgressive does not equal subversive. The two words are often used interchangeably, but they’re very different. To be transgressive is to break the rules of the culture. To be subversive means to undermine the culture, whether deliberately or not, without the culture realising what you’re up to.

Elvis was scandalous, but he was not transgressive. Little Richard was transgressive, but he was not subversive.

There’s a covert “trojan horse” quality to subversiveness that there isn’t with transgressiveness. And it’s that “trojan horse” quality that distinguishes The Beatles from both Little Richard and Elvis — and that might offer us the beginnings of the deeper explanation for Beatlemania, and thus the deeper explanation for the Love Revolution.

To spark the Love Revolution, the lifeforce erotic love of Beatlemania needed to be rooted in transgressive sexuality that pushed against the culture. But to spark a global freakout of the groovy rather than the terrified kind, that transgressive sexuality also had to be subversive — hidden beneath the surface and felt but not seen, so it could get past the restrictive cultural mores of the early 1960s without being censored — or worse.

There’s one more element that early rock-n-roll didn’t have that was required to spark Beatlemania and thus the Love Revolution. And that is, obviously, love.

The seeds of a revolution, like the seeds of anything, need to contain all of the necessary elements for that revolution to grow into maturity. And if there was going to be a Love Revolution, the seeds of that revolution needed to include love. And not just any kind of love, but that sweeping, intense, passionate, regenerative, energy-of-creation kind of lifeforce love represented by the power of the Grail — which is, remember, not chaste spiritual love, not even brotherly love. But rather, intense romantic love combined with the transcendent fire of sexual ecstasy.

Like most music, early rock-and-roll consists mostly of love songs. But regardless of what the actual lyrics are about, early rock-and-roll — and rock-and-roll in general — is deliberately not about love, or at least not that kind of deep, transcendent kind of love we’re calling lifeforce love — which remember is bigger than ordinary love or passion or sexual desire.

Sixties cultural critic George Melly called early rock-and-roll “music to be used rather than listened to,”18 and that’s a crude, but accurate summation. Early rock-and-roll was built first and foremost to be played on the car radio while shagging someone you have no intention of marrying in the backseat of a Chevrolet at the drive-in movie on a Saturday night. And that is, to be clear, a many splendored thing. But it is not love. And it is definitely not the world-changing mythological lifeforce love required to spark Beatlemania and thus the Love Revolution.

Mythologically speaking, if we were to write an ingredient list for Beatlemania to happen as it did, and thus for the Love Revolution to happen as it did, it might be something like this—

For Beatlemania to happen, somewhere at the heart of The Beatles there needs to be a unique, powerful, deeply culturally transgressive source of erotic lifeforce love strong enough to spark a riverbed-changing earthquake and give birth to a new world, but subversive enough so as not to be consciously recognised as transgressive by the larger culture.

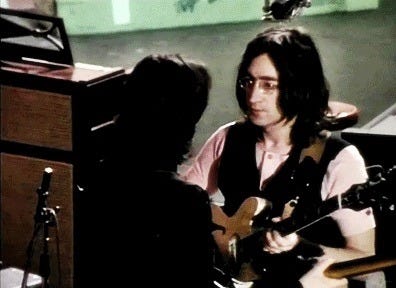

And that takes us back to where we started with all of this — not two thousand years back, but back to me in my little house in the woods in Maine during the darkest days of the pandemic, watching Get Back.

Aren’t certain stories

Best left untold?

—Paul McCartney, Blackbird Singing: poems and lyrics, 1965-1999

I suspect there’s a very specific reason so many of us responded so strongly to Get Back, even beyond our longing to see The Beatles together again.

Get Back is an important piece of history, and I’m wildly grateful for everyone’s work in bringing it into the world, if for no other reason than that it is — to my knowledge — the first time we’ve ever had the near-surreal experience of literally watching a masterpiece (several actually) being created in anywhere close to real time.19

But Get Back is not a feel-good movie, despite its moments of playfulness.

It’s a measure of our intense and urgent need to heal our Fisher King breakup wound, that we so willingly bought into the PR spin that it was a feel-good movie and that it somehow flipped the breakup from grief to laughter and instantly healed all of our pain. It’s a tantalizing pitch — we do love our instant fixes.

But performative smiles for the camera and Peter Jackson’s... creative... editing20 don’t cover up what’s playing out on screen. And as much as we may want and need to heal the wound in this story, we’re not going to do it by forcing a false narrative of happiness over heartbreak.

Get Back John is obviously deeply in pain, strung out on heroin, and acting utterly unlike a man allegedly “in love for the first time.” He’s barely functional enough to string a couplet together, and it’s a testament to both his determination and his genius that he nonetheless manages to come up with half of “Get Back” and “I’ve Got a Feeling” and most of “Don’t Let Me Down.”

Paul is obviously deeply in pain, trying to bite back tears, not always successfully — his perpetually red eyes probably aren’t just from smoking weed — and also not acting at all like a man supposedly newly in love. Paul’s coping by doing what Paul does, pretending everything is fine... just fine... losing himself in the music and in his ability to write masterpieces even when he’s in extreme pain — or perhaps more accurately his in-ability not to write masterpieces even when he’s in pain, and even as it rubs salt in the wound of John’s insecurities about his own inability to write consistently during this time period.21

George is obviously deeply in pain, and also not biting back the tears, as he watches John and Paul, focused exclusively on one another, work on “Two of Us.” In one of the most misinterpreted moments in Get Back, George quits, comes back, and gets happy only when Billy Preston arrives to be a (madly talented) buffer.22

Ringo’s in obvious pain, too — the friend caught in the middle, fantasising about hiding below the storm in an octopus’ garden, and wishing everyone could get themselves sorted and suspecting they probably won’t and loving them all anyway.

Around this tight knot of pain, The Beatles’ royal court of spaced-out insiders and eccentrics orbits them cautiously, perhaps sensing any sudden move could bring the whole thing crashing down around them.23

Get Back is a longer, colour-corrected version of Let It Be with more happy moments edited in — which is a good thing, of course it is — but it doesn’t in and of itself heal the breakup wound, much as we all wish it were that easy. Even if it was a happy movie, it’s too early in the timeline for it to heal anything. They’re not even broken up yet, and the worst is still to come.

But the curious thing is that even though Get Back isn’t a feel-good movie, it made us feel good, and I don’t think it’s just because we bought into the PR.

Get Back reveals things that our collective gaze couldn't see, when Let It Be was released in 1970. Because of this, Get Back has given us the opportunity to pay attention to this story in a new way — which as the Grail story suggests, is the first step to healing that wound.

Get Back is the longest continuous look we’ve ever had — by a large margin — at John and Paul together in any context. Yes, granted, it’s during a difficult period, and with an obvious awareness of the cameras, and again, with Peter Jackson’s imaginative editing — but even so, Get Back is still nearly eight full hours of John and Paul interacting with one another in a way we’ve never before been permitted to see. And it’s this more than anything else that makes Get Back so remarkable.

Prior to Get Back and outside of short and staged events like performances and press conferences, we’d only been allowed to experience John and Paul's relationship second-hand through what we’ve been told about it — much of that in those books based on John’s distorted “we never even wrote together” breakup narrative.

For the first time, we (partly at least) got rid of the middleman and were able to see for ourselves how John and Paul actually were together. And what we saw most definitely did not match what we’d been told for all those years in all those books about that relationship.

Watching Get Back during that winter of 2021, I started to notice what was happening between John and Paul.

How they could barely take their eyes and their attention away from one another. How they mirrored each other’s body language. How they communicated in what seemed to be a private language only they understood and that John has acknowledged they had between them,24 including the fragments of songs they seemed to be playing exclusively for one another as a way of having a private conversation in public.

And then there’s the way their moods seemed to turn entirely on what the other one was doing. Even when George has quit the band, Paul is focused only on why John is late in arriving. And at the moment of decision for the Rooftop Concert, the conversation is between Paul and John and no one else, and it’s John’s support for Paul’s longing to play live again that makes it all happen.

And that’s just the obvious stuff, and during a time when, by all accounts including their own, things were very, very strained between them.

What we saw between Paul and John in Get Back looked a lot more like what Paul’s been saying it was all these years, when he tells us about how “John and I looked into each other’s eyes — the eye contact thing we used to do was fairly mind-boggling. You dissolve into each other... (sic) you would want to look away but you wouldn’t and you could see yourself in the other person.”25

It looked a lot like when Linda said their bond went “deeper than any of us will ever know,”26 and when Yoko observed that “there’s something definitely very strong between John and Paul,”27 and when producer George Martin said “they needed each other like mad”28 and when former Quarry Man drummer Colin Hanton remembered that shortly after they met “something special was growing between them, something that went past friendship as we knew it. It was as if they drew power from each other,”29 and when NEMS employee Alistair Taylor said “they were closer than any two men I’ve ever known.”30

It looked a lot like when John told us, with Liverpudlian understatement, “we do need each other quite a lot.”31

I think what we’re responding to in Get Back— over and above that we respond to all things Beatles because they’re The Beatles — is seeing the obvious love and connection between John and Paul for what it might more truthfully have been, even if we don’t consciously realise that’s what we’re seeing.

Sometime during that first watch of Get Back, I got the first glimmer that maybe... just maybe... there was more happening in this story that I’d been led to believe all these years, in all those books that struggled to even acknowledge that John and Paul liked each other. Maybe John and Paul were more than just bandmates, more than just songwriting partners. More even than the close friends and musical soulmates we now know they were.

The Get Back I saw playing out on my screen on that cold winter night looked to me like two people deeply in love fighting to hold onto one another, even as the world and their personal demons are pulling them apart, cloaking their pain — and their love — in humour and wordplay, music and dancing, denial and subtext, and trying to find their way through it while the cameras roll, George tries to finish a song — any song — and a young and (almost) comically oblivious Michael Lindsay-Hogg natters on about torchlit Arabs in Tripoli.

We had a lot of ground to cover before we arrived here, so I hope you’ll forgive me for holding this back as the plot twist until now — that what set my soul on fire that cold winter’s night is the beautiful possibility that John and Paul were... once again, we don’t have a good word for the complexity of what they likely were to each other... but let’s use the word “lovers,” understanding that’s probably too small a word in the same way that “lifeforce love” is too small a word for the power of the Grail.

When I say “lovers,” I’m not being metaphorical. I’m not suggesting their relationship was a psychosexual partnership or a romantic friendship, as others have done in an often-clumsy attempt to dance around this topic.32 We’re going to talk here about the possibility that John and Paul were actual lovers, with all that that implies.

And since my field research over the past three years has taught me that people have very odd definitions of “lovers” when it comes to John and Paul, let’s define our terms, as best as anything can be defined when it comes to Lennon/McCartney.

By “lovers,” I mean the possibility — the beautiful possibility — that John and Paul were an intentional, long-term, committed romantic couple who were deeply in love, and who desired one another, and who physically expressed that love and desire.

Before you hyperventilate, yes, I’m very aware of the complications involved with having said that out loud. I’ve been working with this material for many years, and yes, we will get to all of those complications in good time.

But please stay with me here and remember my whisper into the wind in the preface asking that you not to jump to snap judgements and conclusions. Because if — and that is an if — it's true that John and Paul were a romantic as well as a creative couple, then this is not — obviously — just another spicy piece of Beatles gossip.

This matters.

A passionate, intimate, transgressive, subversive love affair between John and Paul would be the very definition of the erotic lifeforce love healing power of the Grail.

And if there is truth to the possibility that John and Paul were lovers, then the both transgressive and subversive erotic love between them is the original source of the lifeforce love at the heart of the Love Revolution, and thus at the heart of the mythological riverbed of our modern culture.

And if a romantic relationship between John and Paul is the lifeforce love that’s been stripped out of the story as a result of the distorted “we never even wrote together” breakup narrative, then having stripped the lovers possibility out of the story of The Beatles is the more specific origin of the Fisher King wound at the heart of our world.

And if paying attention to the healing lifeforce love of the Grail is how we heal a Fisher King wound, then paying attention to the possibility of a romantic relationship between Paul and John is a vital and necessary next step in healing the wound at the heart of this story and thus at the heart of our culture.

When I suggest that restoring the possibility that John and Paul were lovers to the story heals the story and thus begins to heal the wound in all of us, this isn’t an abstraction or a metaphor or a bit of poetic exaggeration. It’s literal. I’ve experienced it firsthand. And I’ve discovered over the past years that I’m far from the only one.

As I opened myself to the possibility of John and Paul as a romantic couple, I could feel a part of me that had been numb for as long as I could remember come alive with a new sense of hope and creative energy and a deep effervescent joy — not unlike the feeling of falling in love.

The possibility of a romantic affair between John and Paul quite simply set my life and my soul on fire, and this feeling has stayed with me for over three years and counting with no sign of fading away. And even now, with the hate that’s rising in the world as I record this pressing in on me, that strong and steady flame of lifeforce love burns stronger and brighter than the cold dark night.

I've worked for many years with the mythological stories of Western culture, from ancient Sumerian epic poetry and classical Greek and Roman myths to fairy tales, folktales and religious parables to contemporary mythologies like the death of Princess Diana. No story has ever had anything even close to this effect on me.

Once I had a chance to catch my breath, I recognised what I was experiencing as an encounter with a sacred story — a story that carries the lifeforce love power of the Grail — and more than that, a sacred story of unusual power, because only an encounter with a sacred story of unusual power of could have sparked the reaction I had.

It was this extraordinary, even revelatory, experience that offered me the first hint of what might be the deeper explanation for Beatlemania, because only an encounter with a sacred story could have sparked Beatlemania. And of course, Beatlemania was exactly what I was — and still am — experiencing, albeit in a (somewhat) more grown-up form.

Over the next three episodes, we’re going to do a deep dive into the credibility of the lovers possibility, and some of what I’ve found in my three years of research for this series. None of this will be salacious or sensational, and all of it has been taken from public research, all of it from John and Paul themselves. After those three episodes, we’ll return for the final three episodes of Part One to the story of the story of The Beatles — and what might be the truer and more unexpected ethics question at the heart of the lovers possibility, and how we might resolve it, so that this beautiful possibility can be restored to the heart of the story.

One of the things that makes that possibility credible is that a romantic relationship between John and Paul resolves every major blank spot and inconsistency and logic flaw in the story as it’s currently told — including Beatlemania — and what’s more, it seems to be the only thing that does.

As I started to research this story in earnest, and as the possibility that John and Paul were lovers started to become increasingly more possible, piece after piece of the story that otherwise didn’t make sense began to slide into place. Questions, big and small, that didn’t have good answers began to have obvious answers. Blank spots were filled in, inconsistencies were resolved. For the first time, the story held together as a coherent ‘this leads to that leads to that” narrative.

For the first time, the story became whole, and I mean that in multiple ways — literal, psychological and mythological.

Most obviously, it resolves the mystery of the intensity of the breakup, if not its more specific cause.

We’ll wait to talk in detail about the breakup until we re-tell the story through the frame of the lovers possibility in the second part of the series. But maybe you’re already seeing that the intensity and viciousness of that breakup that feels so bizarrely out of proportion between songwriting partners, bandmates and best friends instantly feels exactly in proportion between two lovers still so deeply and passionately in love that they’re driven to tear each other apart when things go wrong.

And of course, if John and Paul were lovers, that makes John’s breakup narrative not political or cultural, but personal — the venting of pain not in the context of the breakup of the band and the collapse of the Love Revolution, but in the context of a broken heart — and the desire to inflict pain on the person he perceives as having broken it, and we’ll get to all of that eventually.

And then there’s Beatlemania, the inverse of the breakup, that explosion of erotic “and then there was a miracle” riverbed-changing revolutionary joy that we have no scientific explanation for.

An intimate, passionate, yet hidden love affair between John and Paul would account for virtually every element of Beatlemania that historians, sociologists and psychologists have been unable to satisfactorily explain for the past sixty years. Better than anything else, it would account for the intense and deeply transgressive sexual energy at the heart of Beatlemania — sexual energy that otherwise feels all out of proportion to their tailored, sanitised “lovable mop top” image of the time.

A love affair between John and Paul would take us right to the heart of why it was The Beatles — and only The Beatles — who possessed the transgressive, erotic lifeforce power required to spark the Love Revolution, up-end “suffer now, rewards later” and create a new world.

We know from the prior episode, some of the damage done when the original generations of Beatles writers believed John’s breakup narrative that he and Paul never even wrote together — implying, of course, that their relationship wasn’t close. But if what was stripped out of the story wasn’t just a friendship and a close creative partnership, but rather the lifeforce love that powered the Love Revolution, that would without question be the Fisher King wound at the core of the story, and at the core of the wounding in our world.

And that in turn means that paying attention to the lovers possibility by restoring it to the story — not the certainty, just the possibility — is the first step to healing that wound and lifting our world out of the Wasteland and back into the life-affirming, world-changing magick of love.

To put this into perspective, given that the Love Revolution was only the second mythological earthquake in two thousand years, if it was a love affair between John and Paul that set the whole thing in motion, then that love affair becomes the most consequential love affair in recorded history — the only love affair that changed the riverbed of Western civilization and created a new world.33

Like I said, it matters.

There’s obviously a lot more to say about all of this, starting with stepping through in more detail how the possibility that John and Paul were lovers gives us what might be the truer explanation for Beatlemania.

But I realise there's a significant percentage of you who will not be able to focus on anything else I might say about lifeforce love and Grails and healing stories until we deal with some meta issues. And I know from my experience in sharing this possibility with others that some of you might want a bit of time to wrap your head around all of this before we proceed.

So since this is an unusual situation, we're going to do something unusual. I'm going to break off what’s actually the last section of this episode, about how the lovers possibility explains Beatlemania, and put it in a Rabbit Hole — even though it's not a Rabbit Hole, it’s literally the central point of this episode and it would be the last section of it, what we’d talk about next, were it not for the need for the meta-conversation about the lovers possibility.

So this week, there will be two Rabbit Holes — the actual Rabbit Hole, which will be about how I researched this series, which I suspect will now be more interesting than it would have been if I’d shared it earlier. And the Rabbit Hole that’s not a Rabbit Hole at all, but the back part of this episode.

Now let’s deal with the meta of the lovers possibility.

“the thing you’re most afraid to write. write that.” — Nayyirah Waheed, poet

First, I’m well aware of the risk I’m taking in writing the lovers possibility.

The possibility of a love affair between Paul and John has long been the third rail of Beatles scholarship — the thing whispered about but not said aloud, for perhaps obvious reasons that, yes, we will get to.

The possibility that John and Paul didn’t just love each other, but were in love is not exactly a news flash in much of the world of Beatles studies. And neither is the possibility that they acted on that love. It’s been lingering at the edge of mainstream Beatles scholarship for many years, and much more so following the release of Get Back — which seems to have been a bit of a tipping point for both the awareness and the willingness to explore it.

People have been understandably skittish about including the lovers possibility in any kind of formal writing or scholarship, but there’s no shortage of dialogue about it in private “don’t tell anyone I think this but...” conversations, rather than in the public dialogue.

I could have just chosen to enjoy those quiet conversations and the beautiful possibility of Paul and John as a romantic couple, allowing the healing lifeforce of it to quietly enrich my own life without sharing any of it with the world. But as you’ve noticed, that's not the path I chose.

I’ve chosen to take the considerable risk of writing this series — and there are multiple risks, even beyond the ones you might be thinking of — because it’s the best chance I’ve ever had to make a meaningful difference in healing our broken world.

Like most of us, I ache at the accelerating catastrophe I see happening around us — the seemingly unstoppable rise of white Christian nationalism and fascism, not just in America but around the world, the urgency of the climate crisis, the mindless damage to our planet and the creatures who call it home, the out-of-control corporate greed and economic injustice, the troubling abuse of the power of technology and AI, and the rejection of art, literature and humanity in favour of technology, to name a few. Like so many of us, I ache to do something to help that actually makes a difference and isn't just empty gestures and pointless outrage.

Because of my professional experience, I know firsthand that nothing creates sustainable, lasting change more effectively than changing the underlying mythology of a culture. And that by extension, healing the story of a culture creates opportunities for that change at the deeper “riverbed” level — change that can’t be reversed just because the wrong person wins an election.

In short, we do what we can to make the world better, according to our abilities. This is what I can do. So I'm doing it.

One of my favourite moments in doing this work is watching people’s eyes light up with joy when they first discover the lovers possibility. That joy is instant and instinctive. It happens before they’ve even fully processed what I’m suggesting. It’s the joy of healing, the release of tension, the discovery of magick in an unexpected — but entirely expected because it’s The Beatles — place.

I hope that’s happening for you in this moment. But if it isn’t, if the possibility of John and Paul as lovers is making you a little nervous, I understand. And I promise that, within limits, I’m not going to accuse you of being a bigot if you’re one of those people who’s nervous about this. I mean, you might be a bigot, I have no way of knowing — but if you are, it isn’t necessarily because you’re uneasy about the possibility of a romantic relationship between John and Paul. As we’ll explore in detail in the next episode, the reason people get nervous about the lovers possibility is a lot more complicated — and a lot more interesting — than simple homophobia.

Stories are how we make sense of the world. If we’ve grown up deeply attached to a version of a story — and especially a powerful mythological story that sets the pattern for our lives, as we’ve heard it told for all of our lives — and if someone then comes along who tells us that story isn’t what we thought it was, that can feel disorienting and even threatening, even if the newer version of the story is more beautiful and more healing than the old one. And even if you’re someone who genuinely believes we ought be able to love whomever we choose.

What I’m suggesting is, if you’re unsettled, consider giving yourself a little space to get used to this beautiful possibility, before drawing conclusions about how you feel about it.

But meanwhile, please stay with me. I can only speak from my experience here, but for me and for many, many people I’ve talked with over these past years, the possibility that John and Paul were (and in a very real way, still are) lovers brings new layers of complexity and beauty and meaning to the story and the music, and makes it all even more extraordinary than it already is. You may discover as we continue that without the lovers possibility, not only does the story continue to not make sense, but the story and the music as we’ve grown up hearing it turns out to be too small for the majesty of its truth. What I'm saying is, you might find it gets you in the end.

If what's making you uneasy is my saying out loud on a public platform that John and Paul might have been lovers, I understand that, too.

One of the reasons writers have been reluctant to include the lovers possibility in their public work is, of course, the not-insignificant ethical consideration — that if there was a romantic relationship between Paul and John, that love story is theirs and theirs alone to tell or not tell. And until and unless they choose to do that, it’s not a topic that we’re ethically allowed to consider when writing about The Beatles.34

I get that. But given what’s at stake and the potential for genuinely beginning to heal our increasingly broken world, I think we need to do better than staying silent out of unexamined fear and even more unexamined ethical skittishness. I think we need to at least see if there might be a way to include the lovers possibility in the story. Continuing to ignore it — as the nobles in the court of the Fisher King ignore the Grail — risks losing forever the transformative healing power contained in this story, this foundational myth that shapes our modern world.

What I’m saying here is, I think the situation is important and urgent enough that it’s worth the risk.

Obviously, I think there’s a way to talk about the lovers possibility without stepping on Paul and John’s right to tell their own story, or I wouldn't be writing this series. I think there’s a way to restore the lovers possibility to the story in a way that’s respectful and beautiful and that doesn't infringe on Paul and John’s privacy — and that’s what this series is going to attempt to do.

I’ve learned over literal years of considering the possibility of John and Paul as lovers that the ethics involved in all of this are nowhere near as clear and bright as they might initially appear to be — and thus far more difficult to answer in any kind of clear, bright line way. It will, in fact, take all of the remaining six episodes in the first part of this series to fully answer it, because we have a lot more ground to cover before we can deal with the ethics of the lovers possibility in the way it needs to be dealt with.

But in the interests of freak-out management, let’s take a few minutes now and deal with what most people think is the ethical problem with all of this — that regardless of the world-healing benefits of doing so, we can’t include the lovers possibility in the mainstream story because it would be outing John and Paul and it’s simply not okay to out anyone ever.

Well, first off, I agree that, yes, on general principle, we should not out anyone, including, of course, John and Paul. And I get the seductive temptation of a moral absolute. A clear bright line on an important issue in a complex world is — to borrow John’s words — as handy as fucking your best friend.35

But especially when it comes to this story, moral absolutes are tricky because as we’ll see, they tend to get really messy really quickly, and especially in this story.

At its most basic and leaving all the sexual politics out of it, to “out” someone means to disclose a person's sexual orientation without that person's consent. That’s not what we’re doing here — not just because it’s not ethical, but because it’s not actually possible.

Disclosing Paul or John’s sexual orientation would require some kind of definitive proof of either Paul or John’s sexual orientation — and I’m not at all sure how anyone other than Paul and John could know that, any more than anyone other than Paul and John can know for sure whether they were lovers or not.

I speak from personal experience here. Being queer myself, my queerness manifests itself in my life in ways that even I find difficult to untangle. And if someone asked me to put a label on my queerness, I’m not at all sure I could. For sure, there’s no way anyone else could possibly know just from looking at my relationships what my sexual orientation is, and I wouldn’t presume to be able to know that about anyone else, either — which is why we won’t be doing any speculating whatsoever on either Paul or John’s sexuality.36

How Paul and John might personally define their sexual orientation has virtually nothing to do with whether they were lovers. Human sexuality is beautifully complicated and messy and presents itself in a wide spectrum of colours. And what we think of as our primary sexual orientation often bears little relation to who we fall in love with, have an affair with, or even who we marry and choose to spend our lives with. We seem to be obsessed with sorting sexuality into tidy little boxes, but love and desire are what they are, quite independent of the labels we try to impose on them.

I suspect when people object that it’s not okay to write about the lovers possibility because doing so is outing Paul and John without their consent, what they’re really saying is, it’s not okay to openly speculate on a public platform about the possibility that John and Paul were a romantic as well as a creative couple.

Speculation about a relationship is not “outing” — but it is an entirely different and much trickier ethical question, which is why it will take us the remaining episodes of the first part of this series to answer it.

Speaking of ethics, once we’ve laid out the necessary context, I’ll also explain why I made the difficult and admittedly risky and also fairly terrifying decision to release the first part of this series into the world without reaching out to Paul McCartney to ask for his blessing. I have some reason to believe, based on my research over the past years, that Paul might be okay with this, and we’ll talk about why I think that is in a future episode. But of course, there's no way to know until... well, until now, actually.

One thing before we move on—

I’ve spent much of the past three years deeply considering the ethical issues involved in sharing this work, through both research and dialogue with others in a position to offer wise counsel. If you’re feeling the burning need to send me your take on why we absolutely cannot talk about the lovers possibility because ________, please consider that there is likely no opinion on this topic that you’ve come up with since learning about it ten minutes ago that I haven’t thought through deeply and at length.

So with all gentleness, I ask that you please suspend any reflexive outrage you may be experiencing, and withhold judgement until I’ve had the chance to lay out the full scope of this series.37 Again, deep breaths. This is a journey, and we have a long and, yes, winding road yet to go.

And if you find you simply cannot suspend your outrage long enough to listen to a different point of view, there are many, many other Beatles podcasts you can listen to that don’t deal with the lovers possibility at all, or do so only indirectly and in euphemism, and you may be happier listening to one of those.

Before we address the ethics question in detail, we’ll need to address the other objection to including the lovers possibility in the story — that pursuing it as a subject of serious scholarship is a waste of time because there’s nothing to it, John and Paul as lovers is just a romantic fanfic fantasy dreamed up by lovestruck females thinking with our hormones rather than our pretty little heads. And yes, I have had more than one old-school Beatles writer tell me that in almost those exact words.

Putting aside for the moment the self-evident problem with this particular argument, the credibility objection is, of course, not unrelated to the ethics objection for lots of reasons — one of which is that if there’s anything more ethically dubious than talking about someone’s romantic life without their consent (at least so the objection goes), it’s making up stuff about their romantic life without their consent.

Obviously I wouldn’t have devoted a significant amount of time to researching and writing this series if I didn’t think there was “something to it.” But to be clear before we continue — and this may disappoint some of you — it’s not my intention with this series to prove that Paul and John were lovers. First, because I don’t believe anyone other than Paul and John has the right to do that. And second, because absent the kind of proof it would be in poor taste to share (and that I do not have), it’d be daft to think anyone besides Paul and John could prove — or for that matter disprove — something that happened between them in private.

At the same time, if I’m going to suggest we include the lovers possibility in the story, I believe I have an ethical obligation to show that there’s something to it, that it’s not just a flight of erotic and romantic fantasy. And that’s where we’ll pick things up in the next episode, starting with dealing with the “girls can’t think clearly about romantic things” objection — which is, once again, more complex than it might seem, though no less pejorative.

Before we move on, if your concern with the lovers possibility is that it diminishes the role of the women in Paul and John’s lives — most notably Linda and Yoko — here's what I can tell you in advance about that—

We have this idea in Western culture that we’re only allowed to love one person at a time. I think maybe at least some of us know that’s not how life works. The story of The Beatles, and of John and Paul’s relationship, is not a simple story. It’s complicated and messy, and it includes so many love triangles that it’s basically a fractal. And if we're going to tell it truthfully, we need to be willing to embrace the messy complexity of it.

Also, love isn't pie, there’s more than enough to go around, if we soften and allow it to be so.

Okay, next on our list of meta-issues—