All the episodes of Beautiful Possibility in sequence are here.

This episode will work a lot better if you’ve listened to episode 1:1 first.

“London belonged to the young. All the old class structures of our parents’ generation were breaking down. All the old social mores were swept away. No one cared where you came from or what school you’d gone to, what accent you spoke with or how much money you had. All that mattered was what you could do, what you could create. Bohemian baronets smoked grass openly, dukes’ daughters went out with hairdressers, and everyone put two fingers up to the conventions of their youth, and the expectations of their families. The capital was abuzz with creativity, bristling with energy. Everything was possible — and money was not the key to every door. Painters, poets, writers, designers, admen, media figures, and, of course, musicians expressed themselves with fearlessness, freshness and freedom. They wore fabulous frocks and flowery shirts and grew their hair long. They weren’t going to knuckle down and wear the uniform of their class. The rule book had been thrown away.”1 — Pattie Boyd, ‘60s “It’” girl, model, photographer, and former wife of George Harrison and Eric Clapton

It would be hard to overstate the impact of the “earthquake” that hit the world in 1964. The cultural revolution of the Sixties, sparked by the explosion of Beatlemania, changed our world instantly, radically, and though it might not seem like it at the moment, permanently.

It was a matter of speed as much as scale. For only the second time in human history, the foundational mythology of Western civilization was almost completely rewritten, and unlike the other time — the ascent of Christianity, which had taken hundreds of years to reshape the riverbed of the culture — the revolution of the Sixties would do it in less than a decade.

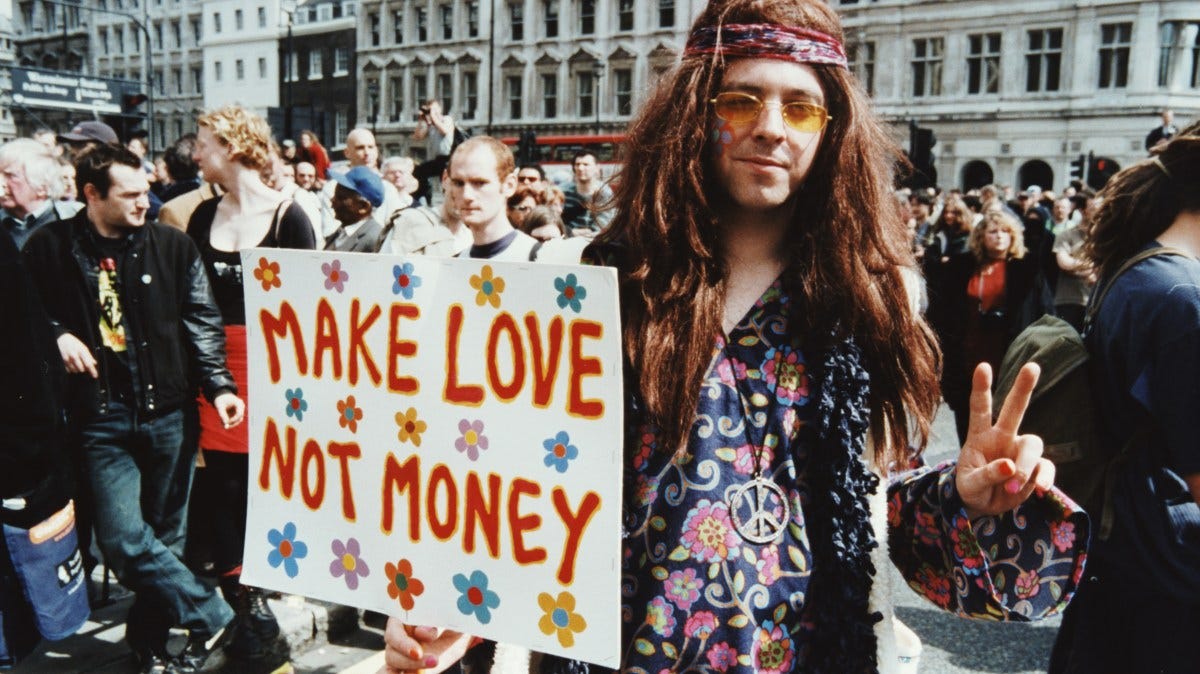

When we talk about the influence of the Sixties, we tend to focus on the artistic renaissance of those years — first and foremost, of course, The Beatles’ reinvention of pop music, and the resulting innovations in the visual arts, fashion, film, literature, journalism, and virtually every other part of Western culture — and always with The Beatles at the centre, setting the pace, continually a step ahead, in their refusal to repeat themselves, pushing the revolution further, faster, onwards.

And then there were the social justice and political uprisings that led — within only a handful of years — to the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, the Peace Movement that helped force the end of the Vietnam War, and the birth of the environmental, second-wave feminist and contemporary LGBTQ movements.

Here’s cultural historian Shawn Levy—

“[In the Sixties] There was the sense that social wrongs could not stand: racial and sexual and class oppression, bullying warfare, unchecked savaging of the environment. In England during the Swinging London years, homosexuality was decriminalized, capital punishment banned, divorce law reformed and censorship of the arts curtailed. Governmental, corporate and social institutions that weren’t utterly abolished seemed suddenly pervious to mass criticism: the class system, colonialism, the Darwinian dictates of capital. These changes — wrapped up gaily, set to a danceable beat and glowing with the optimism of youth — were genuine steps into a more just modernity. If Swinging London was a place where you got a hip haircut and outfit and danced the latest step to a groovy new 45, it was also the place where you opened your mind to a better world.”2

All of these are, of course, important reasons why the Sixties hold a unique and iconic place in our history, and rightly so. But these relatively surface-level advances are not why the Sixties was a mythological earthquake.

Mythological, riverbed-changing earthquakes only happen when our way of viewing the world and our definition of what defines a successful life are fundamentally changed.

The Sixties did that, and this is by far its most important legacy. Even if we don’t consciously realise it, even if it all happened long before we were born, every single one of us has had our lives profoundly shaped by the cultural revolution of the Sixties. We are all fundamentally different people leading fundamentally different lives because of what happened in those brief, shimmering years.

But wait, stop, ‘ang on a second. If you’re thinking we just skipped over, y’know, the main thing we're all here for, well, you're not wrong. It would be better storytelling and much more dramatic, if at this point we could just start with... “On July 6, 1957, two boys who loved rock-and-roll met at the St. Peter’s Church Fete in Liverpool...”

I, too, wish very much that we could do that. And in a perfect world, we could. But this is not a perfect world, and that’s intimately related to the way in which the story of The Beatles is broken. And to tell the more complete story of The Beatles, we first need to understand how and why that story as it’s currently told is broken, why it’s been made to stay broken all of these years, and what we can do to fix it.

I also want to caution you up front that while this episode is going to take us to some lovely places, it’s also going to get a bit bleak, and I know those of us in the US especially are overloaded with bleakness right now, myself included, and you’ve probably tuned in for a series about The Beatles as a bit of an escape and an antidote to the pain.

And that is what this will be — the antidote part, at least — because I have no wish to cause any of us more pain. But if you’re at all familiar with the story of The Beatles, you already know it’s not possible to talk about The Beatles in any depth without encountering pain. And you can take comfort in the title of this series. Although our journey to get where we’re going will sometimes be painful, ultimately this series will be all about beauty, and about the healing power of love.

All of that said, then, onwards.

Imagine all the people, living for today3 — John Lennon

The cultural revolution of the Sixties made the radical suggestion that life doesn’t actually have to suck, and that instead of blindly following the rules and delaying happiness until retirement and a pension or even worse, an afterlife, it might make sense to live more fully in the present.4

This was such a new idea for most people that there aren’t good words for how new it was. And if it doesn't sound all that new, well— that’s because of the Sixties.

You may have noticed in the prior episode that both the pagan mythology and the faux-Christian mythology that replaced it began with “life is hard.” Prior to the Sixties, “life is hard” was an assumption that had never before been questioned on any large scale. It was taken as an axiom — life was hard, and made somewhat deliberately so by the powers-that-be. Suffering was inevitable. The only issue was how to cope with it.

The original pagan foundational myth said, “life is hard, appease the gods and maybe it’ll get a little easier.” The faux-Christian mythology that replaced it — and remember, that mythology had very little to do with the actual teachings of Jesus — promised, “life is hard, but if you follow the rules, you’ll be rewarded after you die.” And the Protestant work ethic adjusted that to, “life is hard, but if you follow the rules, you'll be rewarded in your old age, and after you die.”

But in 1964, after two World Wars and their brutal aftermath, not to mention the assassination of a charismatic young American president who’d promised a new era of opportunity only to be murdered in cold blood before he could deliver, the younger generation had had enough of the suffering. And as for “rewards later,” the long shadow of the atomic bomb made it all too possible there might not even be a later.

The rejection of “suffer now, rewards later” wasn’t in and of itself new. Since the First World War, the younger generation’s growing anger at continual suffering with delayed and often nonexistent rewards had led to scattered outbreaks of rebellion — most notably in America where these sorts of things tend to happen.

During the between-the-wars Roaring ‘20s and the Jazz Age, the Swing Era, and post-war rock-n-roll ‘50s, young people had pushed back the pain of “suffer now rewards later” and the trauma of two “might makes right” wars by dancing, singing and shagging their trauma into temporary oblivion — and note, by the way, how each of those movements took music as its defining element.

Sixties’ activism wasn’t new, either. There’d been a steady push for reform on a variety of social issues throughout the Western world during the first half of the twentieth century. But with a few notable exceptions like the labor movement and first wave feminism, those pushes for reform were short-lived and relatively ineffective. And none of them fundamentally changed the pattern of most people's lives, or their expectations of what a good life should be — meaning that none of them got anywhere close to challenging “suffer now, rewards later” as the foundational myth of Western culture.

So what was different this time? Why didn’t the Sixties just fade into history like every other movement before it? Why did the Sixties — sparked by The Beatles — become a culture-changing earthquake, when all the prior attempts for the past two thousand years had failed? And why do we still hold onto so tightly to it today, in a way we don’t with even the rock-and-roll ‘50s?

Well, to begin with, the people doing the dancing and singing and shagging and the people pushing for social change had never before been the same people. It had always been two separate movements, each pushing against the other — the young people dancing and singing and shagging, and a disapproving contingent of the older generation urging social reform, often because they viewed the dancing and singing and shagging as a symptom of the social ills they were trying to fix. “We wouldn’t have these problems with our young people,” the thinking went, “if only we could fix the _____ social problem.”

In the Sixties, for the first time on any meaningful scale, it wasn’t a battle between the kids who wanted to dance and shag the night away and the stern moralising forces for social reform who wanted those same kids to get serious and help make the world better. Instead, it was the kids who were dancing and shagging who wanted to make the world better. And more than that, those dancing, shagging kids were proposing the stunningly subversive idea that the singing and dancing and shagging is what will make the world better — not just for a night of escapism, but in real, substantial, long-term ways.

When it comes to how we live our actual lives, day-to-day, this might be the single most transformational and revolutionary idea humanity’s ever come up with.

The pagans, most notably the ecstatic mystery cults of Bacchus and Dionysus, understood that music and dancing and sex made life a little less hard, and that it was important to the stability of the culture to offer a socially-acceptable release for our primal urges. The pagans also saw music and dancing and sex as powerful ways of connecting directly with the gods by inducing altered consciousness, and we’ll come back to that in a bit.

But before the Sixties, it had never been suggested by anyone other than a few fringy outliers that music and dancing and sex — and more specifically, the ecstatic joy these experiences give us — might themselves actually be the way to create a better and more meaningful life here on earth.

That’s not even the most revolutionary part of it, though.

Even more radical was the introduction into all that music and dancing and sex and social consciousness — of love. For the first time ever, love became the central organising idea for a global cultural revolution — and by “love,” I don’t mean vague, abstract spiritual love, but human love for our fellow humans, including erotic love.

Love, erotic or otherwise, had never before been the defining element of a revolution, or even a major social movement. Sex, yes — there was plenty of that in the Roaring ‘20s and in the rock-and-roll ‘50s. But never love — and especially never erotic love.

The Christian authorities had ruthlessly stripped from the story of Jesus any suggestion of erotic love, and made it clear that just the mere thinking of sexy thoughts would keep you out of Heaven. And even the “courtly love” of the Middle Ages was about love as a poetic abstraction, a way of styling oneself in the world, rather than a living force in the lives of the people involved.

Humans have, it seems, had a lot of trouble over the course of history acknowledging the power of love.

There’s a lot more that needs to be said about the role of love in all of this, including what we even mean by a word that encompasses everything from our feelings about ice cream to our relationship with the divine. We’ll talk about that in the next episode, along with why — for the Sixties to happen as it did and to become what it’s become — a very specific kind of love was required that was (and remains) unique to The Beatles.

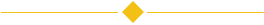

For now, it’s enough to notice that in the Sixties, for the first time ever, the same young people who were dancing and shagging and making music were the ones leading the call for substantive social change in the name of love. “Revolution,” proclaimed a student journalist in 1968, “is the ecstasy of history,”5 and in the Sixties, that was literal. It all came together in a heady, frothy, sexy, joyful, free love “make love, not war” earthquake that healed a generations-old death trauma and, along the way, just happened to completely change everything about what we — and I just might mean the whole world now, not just Western culture — expected and demanded out of life.

For most of us, regardless of our spiritual beliefs, it’s no longer enough to follow someone else’s rules, get married, have kids, slave away for a lifetime at a job we hate, retire with a pension, and hope our suffering earned us a place in some vague promise of Heaven — or even Florida. That approach still works for some people, but most of us no longer feel that’s a description of a life well lived.

Instead, starting with the Sixties, our measure of a successful life began to prioritise happiness and meaning — not in some vaguely defined future or afterlife, but right here in the present. It was the beginning of what almost every single one of us now takes for granted, because it’s all most of us have ever known— the freedom to define our lives by our own, individual standard of happiness and meaning, what we sometimes shorthand as, “you do you.”

Here again is cultural historian Shawn Levy—

After the [Sixties], anything you wanted to do, pretty much, you could — or at least try — in music, fashion, hair, sex, food, living arrangements, you name it. And people would give it a minute’s thought, at least, and not just write it off as a waste of time. Forever after, you would have the license to dress, express and entertain yourself, give yourself over to sensation, investigate a wider world or things beyond it. Doors had opened — hundreds of them — and the hinges were removed from the jambs.6

Everyone alive today in Western civilization — and in most of the world — has inherited from the Love Revolution an unshakeable expectation that we have the right to live our way whether the mainstream culture likes it or not. Obviously, not all of us have embraced this inheritance, but even when we fail to extend that right to others, we recognize that a fundamental injustice occurs when we ourselves are denied the right to live according to our own values.

That right to define our own individual happiness is arguably the single most radical idea humans have ever come up with, and it’s a way of thinking that didn't exist in any widespread form before the Sixties.

It’s not hard to see why this new idea was an easy sell, especially in a world deeply scarred by the consequences of “suffer now, rewards later.”

Two thousand years prior, “life is hard and you’re going to suffer, but at least there will be guaranteed rewards” was a major upgrade from “life is hard, it’s all chaos.” But in the Sixties, “life doesn’t have to be hard and you don’t need to suffer at all” was an even bigger upgrade from “suffer now, rewards later.” The Sixties said fuck suffering altogether, live, love and be happy today.”

All of this was a red-alert threat to the political and economic powers that be, though it took them a while to realise it.

Remember, mythology shapes history, and whoever controls the mythology of a culture controls that culture. If people could no longer be controlled by the promise of rewards in exchange for dedicating the majority of their lives to advancing the interests of those at the top, then all bets were off as to what might happen next. For sure, the low-paid labour that the rich people at the top required in order to generate that wealth would evaporate, if workers got wind of the possibility of a happier, more meaningful life in the now.

Almost as threatening to the old order was the spiritual aspect of the Love Revolution.

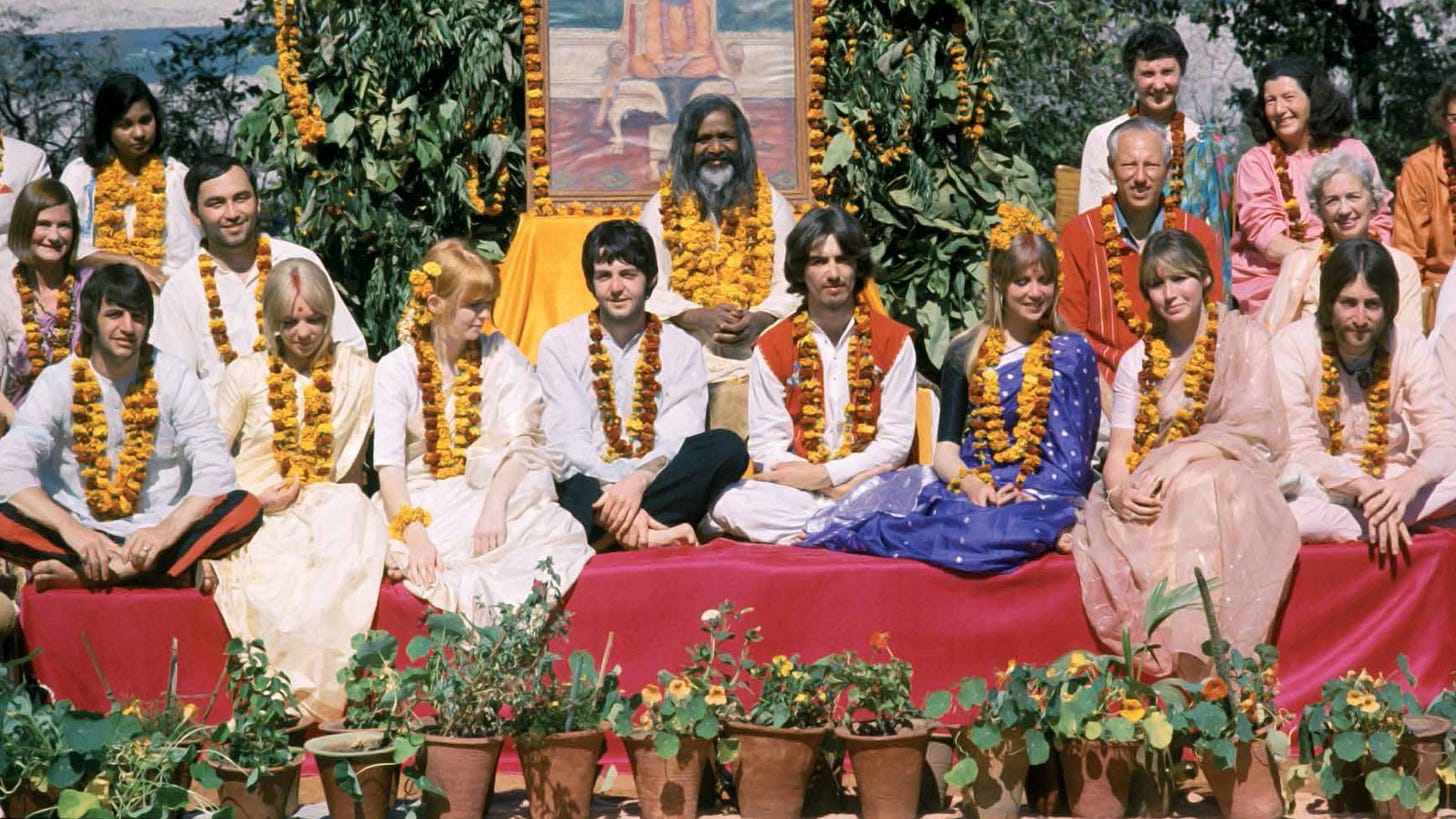

In the Sixties, music and dancing and sex as a way of experiencing and expressing ecstatic love sparked a widespread interest in exploring alternative consciousness with mind-expanding hallucinogens. This in turn led to Western culture’s first widespread exposure to Eastern spiritual practice, sparked by The Beatles’ interest in meditation and their iconic and still-mysterious trip to the Maharishi’s ashram in India — which yes, we will do a deep dive into when we get there in future episodes.7

What we need to know for now is that while it might be hard to believe today, when yoga and meditation are recommended by physicians and therapists and corporate HR people, those things used to be considered sinful and scandalous by the mainstream culture. The Beatles’ interest in Eastern spirituality set off alarm bells among the Establishment, when it introduced meditation to the mainstream Western world as a simple way of being more present in the here and now, rather than as self-sacrificial suffering to obtain a reward in the afterlife.8

Meditation and Eastern spirituality — combined with mind-expanding music, ecstatic dance and the psychedelic movement — reclaimed the power of direct encounter with God (in whatever form you want to use that word) from the institutional Church, which had for thousands of years held onto power by insisting that only priests and other religious authority figures were permitted to talk to God directly, and everyone else had to get the message secondhand — trust us, we’re the only ones who know what God wants, and thus the only ones who know for sure what will get you into — or keep you out of — Heaven.

The rejection of an institutional authority between humans and God wasn’t new — it was in many ways a reversion to original paganism. And of course, every major religious tradition including Christianity has a mystical subculture that seeks out direct encounter with the divine. But direct communication with God had never before happened in such a freeform, open and widespread “do your own thing” way — or for that matter, with as good a soundtrack.

You might already see that this collective discovery of direct access to spiritual revelation and higher consciousness significantly weakened the hold of “suffer now, rewards later.”

Especially for the younger generation, organised religion and its dogmatic, restrictive rule book that had dictated morality for two thousand years became irrelevant almost overnight. No longer did people need to trust church authorities — or any authorities — for instructions on how to live. Beginning with the Sixties, everyone was free to talk directly to whichever God they chose — or not to talk to or believe in God at all — and it turns out there was sod all the Church could do about it.9

When the American Bible Belt burned their Beatles records in 1966 in response to John’s comment that The Beatles were more popular than Jesus, it’s this radical shift away from the faux-Christian “suffer now, rewards later” story that the record-burners and those who whipped them into frenzy were reacting to. And it’s this seismic shift that John is referencing in what he said, although it’s by no means clear he consciously understood it quite that way at the time.10

It was the beginning of “spiritual not religious” as the dominant “religion” in Western culture, and most of us have never looked back.

Two thousand years prior, the pagan-era casino had been traded in for into the corporate factory of “suffer now, rewards later.” But the Sixties offered, if not paradise on earth, then at least the hope that we might be seriously on the way there for the first time ever — and all we had to do to get there was sing and dance and shag. It was the best deal humanity had ever been offered, and for most people, then and since, “suffer now, rewards later” didn’t stand a chance.

Peace, love, freedom, joy... if all this sounds overly simplified and romanticised, well, yes.

Obviously, the Sixties wasn’t paradise fully realised — not in England, not in America, not anywhere. Social problems — poverty, injustice, war, prejudice — didn’t get solved in a magic haze of patchouli incense. And not all of the “live, love and be happy today” ethos was for high-minded, make-the-world-better reasons or even healthy personal reasons. There was the expected share of self-destructive, narcissistic behaviour — plenty of people who just showed up to party and didn't even bother to bring along some good weed to share with everyone else.

Even The Beatles themselves don’t seem to have been looking first and foremost to change the world with their music, at least not consciously and not more than any other artist does. They, along with everyone else involved, had simply been seeking an alternative to the “suffer now, rewards later” lives that were expected of them in the culture they’d grown up in. Creating a new and better world was just a bonus gift with purchase.

What the Sixties was, was a start. A genuine, tangible, substantive, joyful, collective start. And that’s more than had ever happened before in any widespread way.

More than that, remember that we’re looking at all of this not through the hard, granular lens of history, but through the softer, fuzzy — and in this case, more useful — gaze of mythology. And it’s the shift from the hard facts of history to a simpler, softer, more fairytale-like story that signals that the events of history have become something bigger, something mythological. And mythology, as with most of what shapes our perception of the past, tends to be far less about what actually happened and far more about what people think — and even more than that — what people feel happened.

Just like our individual lives are more influenced by our feelings about our fuzzy memories of the past than by the actual facts of what happened, the complex historical reality of the Sixties matters far less than what we remember about those years and how we feel about those memories — even when those “memories” are imprecise, and/or second and third hand.

Regardless of the messy complexities of its reality, the admittedly overly simplified, romanticised story of a revolution of “peace, love and understanding set to a Beatles soundtrack” is more or less how we collectively experience the Sixties.

And that simplified story, rather than the details of the history, forms the mythological riverbed, in much the same way that the “gospels” of the Bible were written by people who didn’t live through the actual events and relied on cultural “memories” of the events being described to craft the Christian mythology. That’s how the soft gaze of mythology works, and it’s that softer gaze that we need if we’re to understand the deeper and more profound effect of this story, and of The Beatles, on our world.

But even so... you might be thinking my fuzzy mythologist’s gaze is so fuzzy that I’ve completely missed something rather big. The promise of the Love Revolution was not realised — peace, love and happiness did not win the day. All the soft focus memories don’t change that the Sixties imploded in a haze of napalm, tear gas, overdoses, assassinations — and of course, the bitter public breakup of those four lads from Liverpool who’d started it all.

And while the Love Revolution did permanently change our definition of a good life, and while that was a mythological earthquake, it’s also true that despite our near-universal expectation that life ought to be about more than just suffering for some undefined future reward, relatively few people actually get the chance to live a life that’s more than “suffer now, rewards later.” And too many people are suffering with no reward at all. And as you’re reading these words today, at least in the US, we’re about as far from the age of peace, love and understanding as we’ve ever been.

So yeah, I did notice that we’re not exactly living in the Age of Aquarius, because I, too, live in the present, albeit reluctantly.

The question is, what the hell happened? How did we fall so far so fast — from the transformative life-affirming ecstasy of the Love Revolution to where we are now, trapped in another bleak chapter in history defined by hatred and violence and despair — increasing numbers of us suffering without any real prospect of reward? Is there a way back to where we once belonged, or is the promise of the Sixties lost to us forever?

To answer those questions, we need to get back to where we started with all of this — back to the question of how and why the story of The Beatles, and thus of the Sixties, is broken, although as we’ll see, wounded might be a more accurate word.

“It's not a great disaster. People keep talking about it as if it's the end of the earth. It's only a rock group that split up, it's nothing important.”11 — John Lennon, 1971

“I would never believe in anything else the way I believed in this music.”12 writer/journalist Alan Light

As we talked about in the first episode, the relationship between a culture and its foundational myth is symbiotic — mythology shapes history and history shapes mythology. Or to return to our analogy, the riverbed shapes the flow of the river, and the flow of the river also shapes the riverbed.

It might be tempting to dismiss the symbiotic relationship between mythology and culture as superstition — like the pagans believing that it was the gods who control the weather. But this dismissal is the result of our mythological illiteracy. The relationship between a culture and its mythology isn’t superstition or magic, any more than it’s superstition or magic that the riverbed determines the flow of the river.

Put another way, because a culture’s foundational myth sets the pattern for the culture, there is a direct cause and effect relationship between the health of a culture's foundational myth and the health of that culture.

If the foundational myth of a culture is healthy and coherent and life-affirming, the culture is overall healthy and coherent and life-affirming. The inverse is also true — if the foundational myth is wounded, then the culture is also wounded. And even more specifically — and this is really the key point in all of this — when the foundational myth is wounded, the culture is wounded in the same way as the foundational myth.

It’s this symbiotic, reciprocal relationship between a culture and its mythology that makes mythology predictive. Just like we can determine the flow of a river by mapping the contours of its riverbed, we can identify the wound in a culture by understanding the wound in the foundational myth of that culture.

To put it more simply, we can understand what’s wrong in a culture by looking at what’s wrong in that culture’s mythology.

Again, this isn’t superstition. In future episodes, we can and will get very, very specific about how this works relative to The Beatles and the Sixties. For now, I’ll suggest that it’s no coincidence that the story of the Love Revolution unfolds almost exactly in parallel with the story of The Beatles. And that it’s no coincidence that the Love Revolution began with Beatlemania and ended with the breakup.

When we say The Beatles conquered the world in 1964, all of this is what we mean. Culture is shaped by whoever controls the mythology. And from the explosion of Beatlemania that became the Swinging Sixties, to the lush, romantic psychedelia of Sgt. Pepper that sparked the Summer of Love, to the fragmented confusion of the White Album that defined the gathering darkness, to the farewell couplet on Abbey Road that wrote the epitaph for both The Beatles and the Sixties, and all of the hundreds of moments in between, The Beatles, more than anyone else, defined the mythology of the Sixties.

All of this is also why the breakup of The Beatles is the most famous — and by far the most culturally traumatic — breakup, not just in music history, but perhaps in all of history. Most bands eventually break up of course, for the usual list of reasons. But this band — and this breakup — that was and continues to be a different thing entirely.

It’s hard to find words for how deeply the breakup of The Beatles broke our collective hearts. When I tell people I’m a Beatles scholar, by far the most frequent question I get is “can you please tell me why they broke up?”

In my experience, this question is never asked out of casual curiosity. There’s a quiet desperation to it, like a lost soul asking a priest why God lets bad things happen to good people, a longing for some kind of explanation for the unhealed pain that’s haunted them for so long that they’ve forgotten that there’s another way of being.

Some of the intensity of our grief can be measured by our depth of love for what we lost.

In the fragmented culture we live in today, where we share next to nothing in common in terms of collective emotional experience, it might be hard to grasp just how passionately and universally we — and by “we,” I really do mean the whole world — fell in love with The Beatles. I don’t think we’ve ever, as an entire culture and maybe an entire planet, loved anyone or anything in quite the same way and with the same intensity with which we fell for those four boys from Liverpool and the music they made together.

We fell fast and we fell hard — fierce and possessive and sometimes violent and out-of-control and on a scale never experienced before or since. Cultural infatuations come and go — that’s the way of things — but for sixty years, through it all, our love affair with The Beatles — and as biographer Peter Carlin put it, “the joyful noise that came so easily to them” — remains way beyond compare.

Maybe even more than the music itself, we fell in love with the unapologetic way the four of them loved and found joy in one another. That love and joy is captured forever in the film footage we have of those early days — in concerts and press conferences and interviews and films, the four of them laughing, teasing, dancing together on that wide open field in A Hard Day’s Night to the ecstatic backbeat of “Can’t Buy Me Love.”13 That joyful, exuberant love is what healed the death trauma of World War II. And it’s what — still today — we can’t get enough of, what we listen for in their music, what we eagerly blur our vision to see the last traces of in Get Back, even as it was all coming apart.

Our collective wounding relative to the breakup comes in large part from the stark contrast between their easy and fierce affection for one another, and the extreme emotional and sometimes physical violence of that breakup. How the four of them — and especially John and Paul — could go from one extreme to the other, from such deep love and affection to bitterness and anger, and especially so quickly and for no clear or obvious reason, is, I think, what we struggle most to come to terms with.

Witnessing that love fall apart — and so viciously — violates our deepest and most fundamental beliefs about how the world is supposed to work. Love like the love we witnessed between the four Beatles — and again, especially between John and Paul — simply isn’t supposed to end with that kind of ugliness. It violates everything we intuitively understand about love.

The breakup unsettles our experience of the music, too. If John, Paul, George and Ringo were no longer in love with one another — or worse, if it’s true that they never had been — then listening to a song like “Because” becomes an experience of cognitive dissonance. The inexplicable but unmistakable ‘blood harmony’ of their voices, blending into a whole greater than the sum of its parts, is as close to a miracle as we’ll likely ever see. How do we reconcile that with how it ended, without making the music itself dishonest?

“Why did they break up?” is by far the biggest and most-asked question in The Beatles’ story, because even if we’re not consciously aware of all the other ways the story doesn’t make sense — and we’ll get to most of them eventually — virtually everyone who knows even a little bit about The Beatles knows that the breakup as we’ve had it explained to us — but really not explained to us — makes perhaps the least sense of all.

When it comes to the breakup, most writers — and even The Beatles themselves — mostly shrug, say “it’s complicated,” and mumble things about business differences and creative tensions and Yoko eating George’s digestive biscuits without his permission. None of it satisfies, and all of it only rubs salt in the wound, because in some ways, an unconvincing or trivial explanation is worse than no explanation at all.

When we lose something we love in a way that makes no sense to us, we struggle to find any kind of solid footing for healing from our grief. Remember, this is one of the reasons story matters so much — stories help us survive trauma by giving us a context for making sense of our pain. If we understand the reason for the pain, it still hurts, but it isn’t experienced as random suffering, and that makes it easier to recover from.

When we suffer a traumatic loss, we need a coherent explanation, so we can heal from our loss. This is why every spiritual tradition includes an explanation for suffering — whether that explanation is that it’s God’s will or as the karmic consequence of our own sins.

Later in this series, we will, of course, devote an entire episode — and likely more than one — to the intricacies of the breakup. But we’re not going to do that yet, because we don’t yet have anywhere close to enough context. And even when we do, we’ll almost certainly never know for sure exactly what happened. As with the breakup of any long-term relationship, no matter how famous the people involved, the vast majority of what took place was behind closed doors, and wasn’t and will never be shared with the world, and that’s probably how it should be.

What matters here isn’t the details of what happened, but our collective emotional experience of the breakup. Whether we lived through it in real time, or whether, like me and probably you, we only know what happened secondhand, through the story as it’s been handed down to us, the breakup was and continues to be a deeply traumatic loss — to the culture overall and to every single one of us, whether we’re conscious of that trauma or not.

Witnessing those once-joyful boys tear each other apart shattered the new idea born out of the Sixties that the transcendent power of love is strong enough to change the world.

If The Beatles, who’d started and led the Love Revolution, had become bitter enemies feuding over money and power across conference tables and in courtrooms and throwing bricks through each other’s windows — the very same “might makes right” they’d led a revolution to get rid of — what hope did the rest of us have to do any better? Why even bother to try to change the world, if the best hope we ever had to escape “might makes right” and “suffer now, rewards later” imploded so disastrously after just a few short years?

And as if the breakup itself wasn’t painful enough, it’s made still more painful by the apparent permanence of it. The specifics are a catechism of loss, knife cuts into an already-bleeding wound. We’re told that after 1969, John, Paul, George and Ringo never played together again. And after 1970, they were never again together in the same room. After he moved to New York in 1971, John never again set foot in England. The last time John and Paul were together in person was in 1976. Every “last time” and “never again” piling on more pain, culminating in the “never again” of John’s murder, which closed the door forever on any chance of seeing those four boys-now-men together again.

The public face of the breakup was painful to witness, but because most of it happened behind closed doors and out of view of the public eye, most of our experience of the breakup, at the time, came from what The Beatles themselves chose to tell us about it.

Ringo, never one to talk publicly about band politics anyway, didn’t say much of anything about it, and was numbing his pain with alcohol and trying (with limited success, it seems) not to take sides.

Paul was doing what Paul seems to do in times of trouble — taking shelter in his music and trying to pretend the whole thing wasn’t happening and that everything was fine... just fine... just as his brother has described him doing when his mother died,14 and as, if we were paying even a bit of attention, we all saw him doing (also with limited success) in Get Back and Let It Be.

George was busy recording his backlog of songs that would become his triple album, All Things Must Pass, but he took more time off than we might wish, to share his thoughts — that he was tired of being Fab and The Beatles weren’t that great, and Lennon/McCartney wasn’t anything special, and Indian music is superior in every way to pop music, and how much better it was to make music with Eric Clapton—

— and honestly, I adore George, of course I do, we all do. I adore deadpan Beatle George and bitchy Anthology George, and I even adore Indian raga music George, because I can relate to anyone whose passion is so all-consuming that it takes over their whole life.

But listening to George’s post-breakup interviews, I want to sit him down on one of his meditation cushions and remind him that he was the lead guitarist in the most important band in history, and that he was a key part of recording the most influential music in history, and that he learned his songwriting craft from the most successful and influential songwriting partnership in history, and that when he did get to record his songs, he was the only person in the world ever who had John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr as his backup band, Paul McCartney as his musical arranger, and George Martin as his producer. So really, seriously, some perspective and tiny tad bit of fucking gratitude would not be inappropriate.

But I digress.

George’s comments are less-than-fun to read, but they’re really just George being George the way George has always been George— which is to say there’s a bit of an Eeyore from Winnie the Pooh quality to them, and especially from the perspective of distance, they don’t have much bite.15 Mostly they’re the comments of a man weary of fame and overwhelmed by years of garden-variety jealousy.

I wish George’s spiritual searching had offered him more of that perspective and gratitude — but in all fairness, however much George presented himself to the world as a sort of junior wiseman,16 even Beatles are human and fallible. And while it’s easy to wish he’d have been more grateful, none of us can truly know what it would have been like to attempt to carve out a creative identity in the shadow of Lennon/McCartney, which is why it’s dangerous to judge anyone through a microscopic glass, as George was fond of saying.17

And then there was John.

John’s breakup-era interviews were not just John being John. In fact, they were the opposite of John being John — or at least the opposite of the John we fell in love with during the Beatles years.

The breakup seems to have changed all of them — how could it fail to? — and in some ways, it seems to have changed John most of all. It’s hard to reconcile Breakup John with the John who’d gazed soulfully at us from the gatefold of Sgt. Pepper as he sang us into a new and better world of strawberry fields and girls with the sun in their eyes. Breakup John seemed an entirely different person, humourless and resentful and cruel, intent on lashing out at the world in what seemed like a deliberate, methodical campaign to hurt everyone he loved and everyone who loved him.

Unlike George, John didn’t just give occasional interviews to promote specific projects. He more or less took the breakup itself on an extended promotional tour, talking to anybody who would listen — which given he’s John Lennon, was pretty much everybody.

John’s breakup anger — rage might be a better word — was big and raw and all-consuming. John would later compare it to the bursting of an infected abscess, and that’s an apt description.18

Over the extended run of his “I’m So Happy I Could Die” Breakup Tour, John pronounced the Love Revolution a meaningless waste of time, and anyone who still believed in it childish and delusional. He declared the Beatles to be “nothing,” insisted that the new music his former bandmates were putting out was rubbish (especially Paul’s), told us that being a Beatle had been “a big letdown” a “sell out” and a “complete humiliation,” and that all four of them had resented their fans. Most significantly, John claimed that Lennon/McCartney was a fiction, that he and Paul had completely stopped writing together in 1962, before they even set foot in a recording studio. And it’s this last thing that — as we’ll see — did far and away the most harm to to the story and to everyone touched by it — which is every one of us.19

Breakup John is the poster child for why creative geniuses in the midst of a mental breakdown probably shouldn't have unsupervised access to the world’s press, but it’s important to be absolutely crystal clear that John is not the villain of this piece — far from it.

It doesn’t take more than basic emotional literacy to recognise that at the core of John’s lashing out was the terrified, deeply insecure little boy of his childhood, in extreme psychological crisis, and whose coping mechanism of choice was to bury his pain in drugs and denial and hostility — all of it made worse still by the mind and personality-altering effects of heroin and aborted primal scream therapy (which was already dodgy to start with), as well as PTSD from unprecedented fame. And maybe most of all, as we’ll talk about in detail when we get there in the story, unmoored by the breakup and by the breakdown in his relationship with Paul.

To cope with all of it, John did what many people do in a difficult breakup. He painted himself as the wounded, innocent party while looking to do maximum damage to his ex — in this case, both The Beatles and Paul, and even maybe the Sixties — as payback and as a defence against the pain.

It’s a testament to John’s strength of character that he managed to live through that time period, much less remain even remotely functional. And it’s a testament to his genius that in spite of everything — or maybe because of it — he was able to write and record what might be music’s most iconic confessional solo album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

So again, John is absolutely not the villain here, and understanding the pain he was in does, at least for me, make his breakup interviews easier to take.

I’m also not suggesting that the breakup is entirely John’s fault, or that he’s the only one who acted badly as it was happening. No one is on their best behavior during a bad breakup, and while The Beatles are an exception in many ways, they’re not an exception when it comes to this.

But none of that undoes the damage done as a result of those interviews.

Whether we lived through the actual breakup or not, John’s breakup interviews made all of us into the abandoned and betrayed children of the twentieth century’s most brutal and consequential divorce, sat down and told by our parents not only that they didn't love each other anymore and were going to live apart, but that they’d never loved each other, or for that matter, us. That it was all an act, a lie, and we're on our own from here on out, good luck, fuck off and goodbye.

John’s denouncement of the Love Revolution was especially painful, delivered as it was alongside images on the nightly news of body bags and assassinations and overdoses and riots. It sent a clear message — the joyful revolution that had inspired a new generation to begin to create a better world had been nothing more than a foolish fantasy. The dream was over, it wasn’t a new world after all, and it was time to wake up and grow up. After all, John Lennon told us so and he ought to know, if anyone would.

Do you see what’s happening here?

First, an earthquake completely disrupts the mythological “riverbed” through which our culture had flowed for thousands of years — a joyful, beautiful, hopeful earthquake, powerful enough to make us believe that life doesn’t have to be an endless grind of “suffer now, rewards later.” That “might makes right” doesn’t have to prevail. That love is more powerful than fear. For a brief shining moment, we believed — truly believed — that the world we long for could really happen. And more than that, we set to work, or rather to play, making it happen — only to have that better world crumble into ruins around us for no clear reason. And on top of that, we were told by none other than one of the creators of that new and better world — by the co-writer of “All You Need Is Love”20 — that the whole thing was a childish delusion and get over it already.21

Again, if you have any kind of emotional intelligence, the truer message of what John said isn’t hard to see. He was almost certainly talking about himself, that he felt he’d been foolish, to believe in the power of love. And if it was all a lie, then there’s no loss when it’s gone. It’s fine, I’m fine. Nothing is real and nothing to get hung about. I never loved you anyway, and you never loved me.

But that’s not the message that we got from the way the breakup was reported in the press. The journalists who interviewed John didn’t understand that kind of emotional subtext, and they mostly don’t seem to understand it even today. Music journalism has rarely been about making sense of the intricacies of the human heart. That’s never been part of the job description — though maybe it ought to be, given making sense of the intricacies of the human heart is arguably the whole point of music.

Instead, journalists simply took John at his word. John was the founder and perceived leader of the band that had started and shaped the whole thing. And if he said this is how it was, then this is how it was. Or at least it was how he felt it was.

The problem is, that it wasn’t how John felt, not really. And it certainly isn’t how it was.

“From some corner of his broken heart, John gave the most bitter interviews, full of hurt and resentment, covered over with the language of violence.”22

John was what they call in journalism “a good interview,” in part because he said whatever he was thinking and feeling in the moment with little to no filter or concern for whether it would still be true five minutes later — which by his own admission, it often wasn’t.

It’s been my experience that while most of us are familiar with John’s breakup interviews, at least in broad strokes, even many Beatles writers aren’t aware that he either contradicted or retracted virtually every negative thing he said on his breakup tour — sometimes in the exact same interview in which he said it.

I certainly wasn’t aware of John’s retractions when I started researching this story. In fact, I put off researching this part of the story for a very long time, because I was angry at John for his breakup interviews and for the damage those interviews had done to the story I loved so much.

That anger is why there are no standalone pieces about John on The Abbey. In the earliest days of writing about The Beatles, I didn’t know how to write about John without my anger bleeding through.

But eventually I had to do the research into John’s breakup tour. And when I did, I found those retractions and contradictions.

John’s retractions of his breakup interviews are going to matter a lot to our story about the story — so before we continue, let’s look at a few examples of why we may want to think twice about believing without question John’s breakup-era version of events.

By far the most infamous stop on John’s Breakup Tour is his extended 1970 interview with Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner. This interview — subsequently published in book form as Lennon Remembers — essentially stands as John’s post-breakup manifesto. And in that same interview in which he said most of the things we just listed off, John also said—

“You know, we all say a lot of things when we don’t know what we’re talking about. I’m probably doing it now, I don’t know what I say. You see, everybody takes you up on the words you said, and I’m just a guy that people ask all about things, and I blab off and some of it makes sense and some of it is bullshit and some of it’s lies and some of it is — God knows what I’m saying.”23

We’ll come back to this, but it’s worth noting before we move on that John’s warning that he was an unreliable narrator was omitted from the article as originally published in Rolling Stone, and only included in the book version.

The Rolling Stone interview wasn’t the only time John acknowledged that he was an unreliable narrator in interviews. John had been warning journalists about his tendency to be less than truthful in interview for years.

Here he is in 1968, talking about his contributions to the official Beatles biography that had been published in 1967—

“So I’m not answerable to everything I said to Hunter Davies. There’s a few bits in there that I said how I felt that day. But do I have to stand by that for the rest of me life because it’s in print?”24

And here he is with Yoko on The Dick Cavett Show, in 1971—

“Well, you see with people like me and yourself, if you're in a certain mood and reporters are sort of asking questions which are angled to get an answer that they need to sell their paper and you're in a certain mood, you'll say certain things to them. And then people bring it back five years later: ‘So you said this, did ya?’ But you've forgotten all about it. You've changed your mood, it's a different day, it's a different year, you know, and you're feeling entirely different. So you're always held up to what you've said before. And half the time you don't know what you're talking about when you're talking to reporters.”

After an interjection by Dick Cavett, John goes on to finish the thought—

“It's like if everybody's words were recorded as they were saying it, there's lots of things you say that either turn out to be silly or you didn't mean it or it's spur-of-the-moment or you meant it or you had foresight or didn't. And it varies, but when people bring it back, you've forgotten all about it. ‘I don't know what you're talking about.’”

John’s making it pretty clear here that we shouldn't take him at his word in interview. But it’s the exchange that follows that makes the point in classic Lennon-esque fashion.

Understandably concerned for the integrity of the interview, Cavett asks John, “Which are you doing now?”

John answers, “How do you mean?”

Cavett clarifies, “I mean, what you’re saying now you actually mean?”

John answers with a non-answer, addressed to Yoko— “I don’t know what he’s talking about. What’s he talking about?” And then back to Cavett— “What do you mean?”25

Instead of answering, Cavett goes to commercial break. John never does answer the question, at least not on camera, and in not answering the question, he’s answered the question. He doesn’t mean any of it, really. He’s John Lennon, he’s playing with words.

John also got specific about retracting his breakup narrative. Here he is in 1972, a year after his pronouncement to Rolling Stone that “The Beatles were nothing” —

“I think [Beatles music is] fantastic. I hear things I hadn't heard for a long time. I get off on a little guitar solo or a lick I've done in the past. "Oh, I didn't know I could play that." Or there's some stuff Yoko hasn't heard which is especially good. I say, "Listen, listen, you've not heard this," because she couldn't possibly have heard all that music... And it's fantastic.”26

I won’t quote it at length here, but John goes on in the same interview to talk excitedly about exactly how one should go about listening to Beatles music to get just the right effect, encouraging people to listen to the UK albums rather than the US albums because—

“ —if you're really going to get into it, it’s best to get them English albums. That's the progression, because as they were recorded, naturally they're in that order. But over here they got jumbled, and you get one year's work mixed up with the year before. So if you're really getting into that, what is it, chronology, you couldn't do it because it was so messed up here.”

John’s love and pride in the music he created with Paul, George and Ringo shines through in this 1972 interview. His words tumble over one another, eager and earnest, and he sounds like any of us when we’re trying to explain to a friend how exactly to listen to music we desperately hope they’ll love as much as we do.27

In 1974, John was asked about his comment during the Breakup Tour that recording with The Beatles meant working on “draggy tracks.”28

Here’s John’s answer—

“It’s not draggy tracks. It’s like draggy tracks as opposed to just completely enjoying it. And that’s the job I’ve chosen to do, is to record and write songs... (sic) If I’m feeling draggy... (sic) I mean, when I say I wrote ‘Good Morning Good Morning’ or something like that, and I didn’t like it, and I didn’t enjoy it, I didn’t mean I didn’t enjoy it as a whole; it was a job of work. But I got enjoyment from doing it. But you can’t pin people like me down on every literal thing that’s said in print like that.”29

Here’s John in 1974, interviewed by Ray Coleman for Melody Maker magazine, in one of my favourite moments in all of John’s post-Fab interviews — when Coleman asks John whether he still regrets being a Beatle, as he’d claimed during his Breakup Tour.

Here’s John’s answer, edited slightly for length but mostly intact in all its rambly, retractive glory—

“No, no, no... I’m going to be an ex-Beatle for the rest of my life so I might as well enjoy it, and I’m just getting around to being able to stand back and see what happened. A couple of years ago I might have given everybody the impression I hate it all, but that was then. I was talking when I was straight out of therapy and I’d been mentally stripped bare and I just wanted to shoot my mouth off to clear it all away. Now it’s different. When I slagged off the Beatle thing in the papers, it was like divorce pangs, and me being me it was blast this and fuck that, and it was just like the old days in the Melody Maker, you know, ‘Lennon Blasts Hollies’ on the back page. You know, I’ve always had a bit of a mouth and I’ve got to live up to it... Now, we’ve all got it out and it’s cool. I can see The Beatles from a new point of view. Can’t remember much of what happened, little bits here and there, but I’ve started taking an interest in what went on while I was in that fish tank. It must have been incredible! I’m into collecting memorabilia as well. Elton [John] came in with these gifts, like stills from the Yellow Submarine drawings and they’re great. He gave me these four dolls. I thought, ‘Christ, what’s this, an ex-Beatle collecting Beatle dolls?’ But why not? It’s history, man, history!’”

John goes on in the same interview to add—

“So y’see, all that happened when I blew my mouth off was that it was an abscess bursting, except that mine as usual burst in public... When we did a tour as The Beatles, we hated it and loved it. There were great nights and lousy nights... I’ve got perspective now, that’s a fact.”30

Here he is again in that same interview—

“I went through a phase of hating all those [Beatles] years and having to smile when I didn’t want to smile, but that was the life I chose and, now I’m out of it, it’s great to look back on it, man. Great! I was thinking only recently – why haven’t I ever considered the good times instead of moaning about what we had to go through? And Paul was here and we spent two or three nights together talking about the old days and it was cool, seeing what each other remembered from Hamburg and Liverpool.”31

After slagging off the Love Revolution in 1970, here’s what John has to say about it in 1980—

“The seeds that were planted in the 60s—and possibly they were planted generations before—but the seed...{sic} whatever happened in the ‘60s, the flowering of that is in the feminist, the feminization of society. The meditation, the positive learning that people are doing in all walks of life... (sic) that is a direct result of the opening up of the ‘60s.”32

And in another 1980 interview, his famous quote—

“If someone thinks that love and peace is a cliche that should have been left behind in the 60s, that’s his problem. Love and peace are eternal.”33

Here he is in 1972—

“I still believe in the fact that love is what we all need, that makes us all so desperate, frenetic, or neurotic, et cetera, et cetera. But I still believe there's many ways of getting to that situation. There's a lot of changes in society to come before we can ever get to a state of even realizing that love is what we need, you know? But I still believe in it. And I've read cracks about, "Oh, the Beatles sang 'All you need is love, but it didn't work for them,’ you know. But nothing will ever break the love we have for each other, and I still believe all you need is love.”34

John’s reaffirmation of the love the four Beatles had for each other brings us to arguably the most infamous and, as we’ll see, ultimately the most damaging, part of John’s Breakup Tour — the bitter and often dismissive things he said about Paul in those interviews.35 Those comments and their context require a much longer conversation, and we’ll dive into that in a big way in an upcoming episode, because in many ways, it’s the deeper wounding in all of this and the focus of this series.

For now, let's talk about that infamous claim John made to Rolling Stone that he and Paul stopped writing together in 1962.

As we saw earlier with Lennon Remembers, John was not only an unreliable narrator from year to year and even interview to interview, he frequently contradicted himself within the same interview — not that anyone seemed to notice or care.

First of all, John contradicts himself on this literally five seconds after he’s said it. Then he says it again and five seconds later, contradicts himself again. Because, as he admitted later, he was lying and he knew it.

Wenner asks him when his songwriting partnership with Paul ended. John answers—-

“That ended … I don’t know, around 1962, or something, I don’t know. If you give me the albums I can tell you exactly who wrote what, and which line. We sometimes wrote together. All our best work — apart from the early days, like “I Want to Hold Your Hand” we wrote together and things like that — we wrote apart always. The “One After 909,” on the Let It Be LP, I wrote when I was 17 or 18. We always wrote separately, but we wrote together because we enjoyed it a lot sometimes, and also because they would say well, you’re going to make an album, get together and knock off a few songs, just like a job.”

In the space of a single quote, John contradicts himself three times. The partnership ended in 1962, but “we sometimes wrote together.” And actually, “all our best work... we wrote together.” “We always wrote separately, but we wrote together because we enjoyed it a lot.”

As if there wasn’t enough, a little later in that same interview, Wenner asks, “what songs really stick in your mind as being Lennon-McCartney songs?”

John answers with—

“I Want To Hold Your Hand,” “From Me To You,” “She Loves You” — I’d have to have the list, there’s so many, trillions of them. Those are the ones. In a rock band you have to make singles, you have to keep writing them. Plenty more. We both had our fingers in each other’s pies.”36

We’ll talk more about those finger pies in the next episode, but for now, once again a little later in the same interview, Wenner asks about Sgt. Pepper and John answers—

“[Sgt. Pepper] was a peak. Paul and I were definitely working together, especially on “A Day In The Life,” that was a real… (sic) the way we wrote a lot of the time: you’d write the good bit, the part that was easy, like “I read the news today” or whatever it was. Then when you got stuck or whenever it got hard, instead of carrying on, you just drop it. Then we would meet each other, and I would sing half, and he would be inspired to write the next bit and vice versa. [Paul] was a bit shy about it because I think he thought it was already a good song. Sometimes we wouldn’t let each other interfere with a song either, because you tend to be a bit lax with someone else’s stuff, you experiment a bit. So we were doing it in his room with the piano. He said, “Should we do this?” “Yeah, let’s do that.”37

There are more references like this in the Rolling Stone interview, relative to specific songs. It’s not clear if Wenner even notices the contradictions, because he doesn’t press John on them or even ask him to clarify.

Here’s John again in 1976, talking with friend and DJ Elliot Mintz about his public fight with Paul during the breakup—

“It's not that we didn't like each other. It's that I've compared it to a marriage a million times and I hope it's understandable for people who aren't married, or in a relationship. It was a long relationship. It started many many years before the American public or the English public for that matter knew us. Paul and I were together since he was 15 and I was 16, and George was whatever, you know. It's a long long time for the four of us were being together. And what happened was, through boredom and through just the too much of everything and people bothering us with business, the whole pressure of it finally got, you know, like people do when they're together, they start picking on each other. You know, it was like, it's because of you, you got the tambourine wrong, that my whole life is a misery, you know. It became petty, but the manifestations were on each other 'cause we were the only ones we had.”38

And here he is again, in 1980, when interviewer David Sheff specifically asks him about that same “we stopped writing together in 1962” comment—

“No, no, no. I said that, but I was lying. By the time I said that, we were so sick of this idea of writing and singing together, especially me, that I started this thing about, ‘We never wrote together, we were never in the same room.’ Which wasn’t true. We wrote a lot of stuff together, one on one, eyeball to eyeball. Like in 'I Want to Hold Your Hand.” I remember when we got the chord that made the song. We were in Jane Asher's house, downstairs in the cellar playing on the piano at the same time. And we had 'oh, you-u-u ... got that something ...' And Paul hits this chord and I turn to him and say, 'That's it!’ I said 'Do that again!' In those days we really used to absolutely write like that - both playing into each other's noses.39

While the John of later years still frequently allows his insecurities get the better of him when he talks about Paul, he also doesn’t seem all that committed to it when he does. If he was, as he claims, lancing an abscess during the Breakup Tour, then by 1972, there’s a sense that he’s performing it in an increasingly detached way, like an actor playing a character he no longer identifies with.

Maybe that’s rooted in his comment about having a reputation as a loud mouth and needing to live it to it, but there’s also a much more intriguing possible explanation that we’ll talk about when we get there in the story, for why John may have felt the need to continue to perform his “feud” with Paul even after their reconciliation.

Still, it’s the original comment in Lennon Remembers that did far and away the most harm. I suggested earlier in the episode that we can identify very specifically when the wounding to the story happened. This comment — that they’d stopped writing together in 1962 — more than any other from John’s Breakup Tour is the beginning of ithat wounding, and we are all still suffering the fallout from it to this very day. It’s the moment when John made Lennon/McCartney into the fiction, and we’ll spend the rest of part 1 of this series — off and on — working our way through what happened as a result and why it matters.

For now, let’s close this section with John’s comment in 1968, at the beginning of all the breakup madness—

“People are going to be writing about us for the rest of our lives probably, and after we’re dead, so I tend to either confuse the issue so much they never knew what was going on or to try to keep shoving out bits and pieces of what happened, and how the different things happened as a result of this or that or how I was influenced or not influenced. So whoever is bothered to be looking at it in the future, if they ever do... (sic) But people that really know will sort that out... (sic) They’ll know what was going on with it, and they won’t have to go through a million, million things, y’know? Just like that.”40

You might want to come back and revisit this quote after the next episode, but for now, in part because of John’s tendency to confuse the issue, and journalists’ tendency to believe him, we do in fact have to go through a million million things to find out what was going on, y’know? Just like that.

Untangling the contradictions and retractions in all of John's interviews, and especially from the breakup all the way through to 1980, would in and of itself take an extended episode, a bulletin board and lots of red string. But I think you get the gist.

These are just a few of the more obvious examples — there are many, many more. It’s not that big an exaggeration to say that John spent the second half of the ‘70s — to the extent he said anything at all — telling everybody he didn’t mean what he’d said in the first part of the ‘70s.

The retractions and contradictions I’ve shared here are not obscure, and finding them doesn’t require any specialised research or access. I’ve made a point of deliberately pulling them from major interviews that are easily accessible — most of them included in a widely available 2017 collection of John’s major interviews.

The point here is that over and over again, John warned interviewers he was an unreliable narrator. Over and over again, sometimes in the same interview, he contradicted and retracted his bitter, distorted breakup narrative.

And it’s also worth noting that John consistently retracts and expresses regret only for his negative comments. I’ve found no examples whatsoever in which he’s ever retracted or expressed regret for a positive comment, whether about the Beatles, the Sixties, or about his relationship with Paul.

I get that the journalists who conducted these interviews didn’t have the ability to understand the emotional subtext of why John said what he did on his Breakup Tour. But one would hope they’d at least have had the ability to listen to their own interviews and to what John was actually saying and to realise that at the very least, it was more complicated than it was made out to be to the press.

But with one exception — which I’ll footnote — no.41

For reasons we’ll get to in a future episode when we have more context — and including the simple fact that conflict and negativity sells newspapers — journalists believed the worst of what John said, took it at face value, rejected almost everything else, and wrote their articles and interviews accordingly.

As for the Rolling Stone interview, one might think that, especially as publisher and editor-in-chief, Jann Wenner would have taken the time to actually listen to what John said in the interview before deciding how to approach its publication, especially considering how inflammatory so much of it was.

But also — no.

Instead, Wenner turned the interview into not one, but two separate cover stories spanning two issues of the magazine. And no sooner was the ink dry, then he also released it — over John’s repeated objections — in book form.

The flyleaf of the original 1971 edition of the book begins with a quote from journalist Andrew Kopkind about how John’s interview “breaks through the layers of dream-webs which have solidified around the culture, freak consciousness and political revolution.” That's a pretentious way of saying, stop being so naive and grow the fuck up.42

On the back flyleaf, Kopkind weighs in again, calling the interview “a revival of honesty.”

In his own comments on the flyleaf, Wenner starts, of course, by waxing poetic about all the groupie sex The Beatles supposedly had, because... priorities. He then goes on to call the interview, “the honesty of an amazing man in a world gone mad” and “one of the most extraordinary manifestos from an artist at any time in history about his own hopes and fears and the sources of his vision.”

Honesty, honesty, honesty. Wenner seems to be trying to convince himself.

But it’s a single sentence in the introduction that’s really the coup de grace. Writing in 1971, Wenner calls Lennon Remembers “the statement (he italicizes the the for emphasis) about the end of the Beatles, because John was the leader of the group.”

In November 1971, following the publication of Lennon Remembers, John wrote the following letter to Wenner—

“As your company was failing (again), and as a special favor (Two Virgins was the first), I gave you an interview, which was to run one time only, with all rights belonging to me. You saw fit to publish a book of my work, without my consent—in fact, against my wishes, having told you many times on the phone, and in writing, that I did not want a book, an album or anything else made from it.”43

John requested that the letter be published in Rolling Stone as his response to the publication of the book. Wenner refused.

Lennon Remembers is still in print today. The year 2000 edition features that same introduction, as well as the usual collection of blurbs on the back. And also a new introduction, in which Wenner offers no corrections, no addendums, no acknowledgement of John’s retractions and regrets, and no acknowledgement of John’s objection to its publication or explanation for why he chose to publish it the first time, much less a second time.44

Instead, Wenner says he remains “enchanted” by the interview, and calls it “passionate, unnerving and honest.” “Lennon Remembers,” writes Wenner, “overwhelms you with a real sense of the man, who he was and what he felt like.” Wenner goes on to say that “other than in some of his records, this interview is the only place I’ve had such a sense of John Lennon.”45

By the way, Yoko adds her thoughts, too, and in this case, she’s the only one who gets it right, when she says, “people with weak stomachs should close the window before reading. You might just feel like jumping out.”

That about covers it, yeah.

In his memoir, published in 2022, Wenner recounts the story himself. He leans heavily — again no surprise — on how “truthful” it was, saying that “to read it is... to know John Lennon.” He acknowledges only in vague terms John’s retractions, saying he was “sure John would have liked to take back some of what he said,” as if John hadn’t tried to take it back even in the interview itself, and over and over in interviews that followed. Wenner offers only a lukewarm acknowledgement of the devastation that the interview visited on Paul’s life, with no acknowledgement at all of how Rolling Stone continued for decades to savage Paul’s career with its vitriolic reviews.

The icing on the poisoned cake is Wenner’s claim that publishing Lennon Remembers against John’s wishes “tore him apart” and “made him feel sick inside”— a claim that rings fairly hollow, given John had been clear that the interview was not to be published beyond the one time, that no one was forcing Wenner to publish it as a book, and that he’d boasted a few paragraphs earlier that the interview sparked a flood of toxic headlines and put Rolling Stone on the musical map.46

I suspect that even beyond the desire to sell books with a sensationalist marketing campaign, it's really, really important to Jann Wenner to believe that John was being honest in this interview, and we’ll talk about why in the next episode.

I’m not suggesting here that the original Rolling Stone interview shouldn't have been published. The interview stands as an important record of John’s state of mind at a pivotal moment in history. And while the interview that became Lennon Remembers is longer than his other breakup interviews, it’s not substantially different.

The book is another story. Publishing it over John’s objections, and worse, as an honest reflection of who John Lennon is as a person for all time, which is what Wenner has chosen to do, is another matter altogether.

The damage here extends beyond the book itself. Out-of-context quotes from Lennon Remembers and other breakup interviews are endlessly recycled into headlines on YouTube videos and on the trashy, click-baity music websites that play fast and loose with the truth in order to sell ad space, and all of those click bait headlines emphasize and revel in the toxicity of John’s distorted narrative.

If you’re surfing the web and you see some kind of nasty headline about how The Beatles didn’t like each other or John hated Paul or anything else of that ilk, you can bet that it’s based on a single, out-of-context quote from John’s Breakup Tour — and probably from Lennon Remembers.

I realize that for some of you, as painful as John’s words are, it feels disloyal to suggest that he was not telling the truth in those interviews, in spite of all of his retractions. Part of John’s cultural power is the perception that he’s a truth teller — and in his art, he unquestionably was because great art is by definition founded on truth.

But we do John, Paul, this story and everyone affected by it — which is all of us — a grave disservice when we hold him to those words.

Lennon Remembers, and really all of the breakup interviews, was John at his absolute worst — bitter, angry, heartbroken, confused, disoriented, struggling with depression, low self-esteem and fear of abandonment. Over and over, John told interviewers he regretted his distorted breakup narrative. Over and over, he said it wasn’t honest, that he hadn’t meant to do harm, that it wasn’t who he really was.47

What would it be like, to have your worst self, your rawest, least considered, most-regretted words spoken at a moment of deep pain and confusion enshrined forever as the “honest” story of your life?

The breakup interviews stand not as a testament to the real John Lennon, but as a testament to the way in which over the past fifty years, the music press has distorted and corrupted this story — this foundational myth of our modern world. To be fair, it wasn’t only the press that did this, but it’s too soon to talk about anyone else — you and I don’t know each other well enough yet.

So for now, let’s talk about the press and how they’ve twisted this story out of its truth and into anger, pain and resentment, hurting people in the process — mostly, as we’ll see in a future episode, Paul, but also John, and everyone who loves them and this music. Partly out of ambition and a desire to sell more magazines, but mostly — as we’ll see in a future episode — out of fear.

“John raised his voice for peace. For love. For brotherhood. How I wished he had gone into the bowels of hell where kids were on lethal drugs and taken them by the hand and healed them. He could have done it, more than anybody I know. But what he couldn't do on earth, maybe — God willing — he can do in death.” — essay by a fan in a tribute magazine shortly after John’s murder48

As if the breakup-era interviews hadn’t done enough damage, John’s murder in 1980 made things so, so much worse — I mean, obviously. But also because losing him so unexpectedly and violently inevitably canonised him into a secular saint whose every word was now a holy and infallible revelation to be treated as gospel (and wouldn’t John have been both amused and irritated by that).

Of course, this would have happened regardless — but the breakup interviews added a new and damaging dimension to it.

It’s likely that in the wake of his murder, questioning John’s honesty felt disrespectful — not just because of the “don’t speak ill of the dead” convention, but because no one wanted to diminish his genius by questioning the truthfulness of his words.

It’s also probably that, as we’ll talk about in a later episode, the image of John that was canonised was the edgy, truth-telling revolutionary, and the breakup interviews fit into that image.

And I wonder if it might have been a bit more than that, too — if maybe the reluctance to question John’s version of the story also had to do with knowing we’d never get any new words from him. The ones we had would have to last us forever, and discrediting any of them meant there was that much less of him in the world to hold onto.

John’s murder also had consequences for the story of The Beatles. The global outpouring of grief had brought the Fabs back into the forefront of the zeitgeist, and that in turn inspired the writing and publication of the first serious biographies since Hunter Davies’ official biography in 1967.49